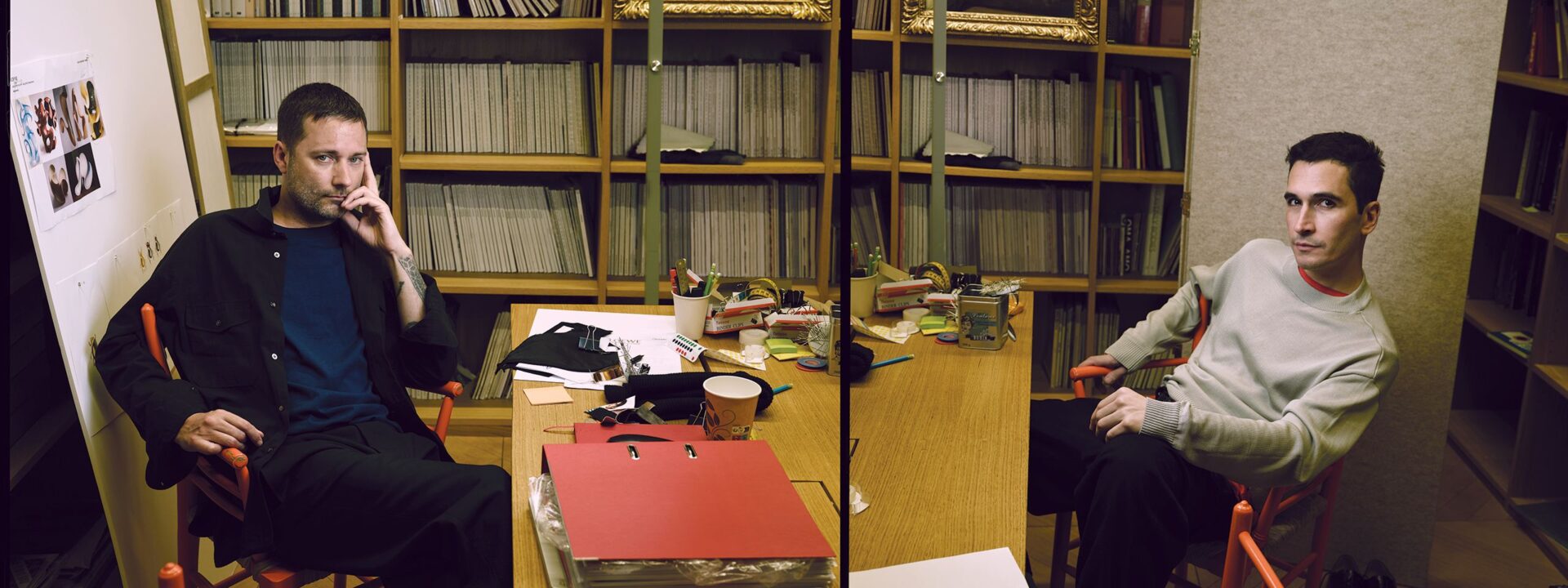

Could someone fall in love with a piece of leather? I wouldn’t have thought so, but on this warm June day in Paris, Lazaro Hernandez is looking at one with such passion that I’m starting to reconsider. “It looks painted, doesn’t it? Like watercolor—or Rothko, the way the colors blend together… But it’s not. Look—it’s layers of leather. The technique is old, it’s called skiving, but this is a new way of doing it.” Hernandez goes on like this, sounding like a friend excitedly recounting a perfect first date. Meanwhile, his partner in work and life, Jack McCollough, is trying out a bucket bag in front of the mirror (“How’s the slouch?”) as the Loewe design team watches.

In January, Hernandez and McCollough announced they were leaving Proenza Schouler, the brand they started 23 years ago as students at Parsons. By April, they had packed up their life in New York—the only home they’d really known as adults—and moved to Paris to become the new creative directors of Loewe. The day I meet them at the brand’s headquarters near Place Vendôme, their belongings are still in boxes, and they’re staying in a temporary sublet in the 7th arrondissement. As McCollough says, they haven’t had time to find their “real place” yet—taking over a major luxury house is all-consuming. Not only do you have to chart the brand’s future, you also have to learn your way around the building. Case in point: during a tour, Hernandez pauses and asks, “Wait—there’s a kitchen on this floor?”

Hernandez and McCollough are just two of many designers settling into new roles this year. Fashion is undergoing a historic shift—it’s as if all the dials turned at once, and the biggest names decided, almost in unison, that it was time for a fresh perspective. The Spring 2026 shows in September alone will feature a dozen labels with new designers. Some are fresh faces, like Michael Rider stepping out from behind the scenes to succeed Hedi Slimane at Celine; elsewhere, it’s a game of musical chairs. Matthieu Blazy was adored at Bottega Veneta before moving to Chanel, for example, and Hernandez and McCollough’s predecessor at Loewe, Jonathan Anderson, has moved on to Dior. Rewind a season or two, and the pace of change becomes even more striking: Chemena Kamali at Chloé, Sarah Burton at Givenchy, Haider Ackermann returning at Tom Ford—the list goes on and on.

“These last few seasons in Europe, you could really feel it. We’re at the end of a cycle,” says Moda Operandi co-founder Lauren Santo Domingo. “I kept thinking Jack and Lazaro should be here—we need new energy, and they’re always moving forward.”

Of all the designers involved in fashion’s great reshuffle, Hernandez and McCollough are the only ones who have never worked at a luxury house before—they’ve never seen how the gilded machine operates. Their first visit to the Loewe factory in Getafe, outside Madrid, left them in awe. “Some people have been working there for 50 years—incredible artisans,” McCollough says. “And all these hundreds of people are looking at us like, Okay, what can we make for you?”

“I think it’s going to be wild,” speculates W editor-in-chief and longtime friend Sara Moonves about their debut Loewe collection. “All we’ve ever seen them do is Proenza,” an independent American brand focused on sharp, directional sportswear. “Their creativity, their curiosity, their sophistication with materials and technique—where will they go with the full force of Loewe behind them?”

Moonves isn’t the only one wondering. We’re all eager to see what their Loewe will look and feel like—and where it will fit in this transformed fashion landscape. The speculation feels bigger than just clothes, bags, and shoes. Even so, as I walk through Loewe’s headquarters, I find few clues among the hanging collections.The last designs by Anderson hang on the press team racks. I notice a mood board—it’s abstract. The only hint of what a Hernandez-and-McCollough-led Loewe might look like is a roughly six-inch leather swatch that Hernandez is raving about. It’s made of whisper-thin strips joined by a new skiving technique, creating a seamless, suede-like color field.

Another clue is a designer named Camille, whom Hernandez introduces. She spent five years perfecting this process with artisans in Getafe to achieve an intarsia-like effect. “Cool, right?” McCollough says as he strolls over. Usually the quieter of the two, his eyes say it all: he’s just as captivated.

“It’s always been just the two of us, bouncing ideas off each other—and now, to have someone bring us a technique they’ve worked on for five years…” McCollough trails off, shaking his head in amazement. “We’ve never had access to anything like this.” I later learn they’ve used this skived leather in their debut collection, weaving it through bags, shoes, and ready-to-wear to, as Hernandez puts it, “tell a full story.”

It’s their story, told through the language of relaxed, all-American sportswear—parkas, jeans, T-shirts, and more. But it’s a story that could only be written here in Paris.

McCollough admits that neither he nor Hernandez had spent much time in Paris before moving there for the Loewe job. Walking through the city, they look around wide-eyed, like tourists. Neither speaks French. Yet in their atelier, deep in work, they seem completely at ease—and also dazzled. In other words, they seem happy.

And that’s another clue. Joy fuels creativity, and it shows in the clothes. The mood is very Loewe: “Cerebral, but playful,” as CEO Pascale Lepoivre described the brand’s ethos in a conversation where even she admitted she doesn’t know where McCollough and Hernandez are headed. “If we knew everything already, what would be the point?” she said. “The whole point of change is to be surprised.”

But what are we all waiting for? What do we really want—not just from Hernandez and McCollough at Loewe, but from all these new designers and this fashion reset? When I spoke to Santo Domingo, she described a sense of limbo in fashion, something she feels both as an insider and as a shopper endlessly scrolling. “It’s like everyone’s waiting for what’s next, but it’s not here yet.”

I think she’s pointing to a modern experience: the mix of boredom and restlessness that comes from too much bland content. If you’ve ever spent half an hour flipping through streaming options only to turn off the TV, you know the feeling. So much available, yet nothing you actually want to watch.

NEW YORK GROOVE

Then, Proenza Schouler wunderkinds McCollough and Hernandez stand with models at their 2004 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund presentation. Photographed by Arthur Elgort, Vogue, November 2004.

Loewe stands apart from this gloomy narrative. Under Jonathan Anderson’s leadership, its revenue quadrupled over a decade. It proves that people crave fashion that challenges them rather than just catering to familiar tastes. “People need a sense of discovery,” Lepoivre says. Anderson, through his collections, campaigns, clever TikToks, and the launch of the annual Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, always dared you to be intrigued. Now, his admirers are eager to see if his legacy is in good hands. Hernandez and McCollough know this but are determined to ignore the pressure.

“It doesn’t help us,” McCollough notes.

“The opposite,” Hernandez adds.

“We’re approaching this as the start of a process,” McCollough continues. “A lot of people expect big ideas right away, but…”Even when you consider Jonathan: he didn’t build Loewe into what it is today overnight. For this first season, the most important thing is capturing the right feeling.

“And not a manufactured feeling,” Hernandez adds. “Something true to us, but interpreted through the house’s codes. Us, but as Loewe.”

We’re having this conversation while walking through Paris, a city steeped in fashion history. It’s a challenging time for these two Americans to be writing their own chapter in that story. Fashion evolves alongside the world, and when the world is in turmoil, the ripple effects are unpredictable.

Hernandez, McCollough, and I grew up in fashion together, during an era dominated by spectacle—increasing hype, outfits designed for social media, and runways pushed to their commercial limits. The goal was business: selling bags in Russia, China, or Dubai. It was a globalizing age that fed on immediacy and virality, and it made sense for brands to chase mass appeal.

I believe that era is over—and not just because of rising tariffs or nationalism. Small signs point to it, like Lepoivre casually mentioning that Loewe can no longer depend on a few star items becoming global bestsellers. “Before, it was the same everywhere,” she says. “Now, from Japan to Europe to America, tastes and trends differ—even functional expectations. For example, the Japanese still buy wallets because they still use cash—unlike anywhere else. So you have to be more local, more precise.”

As the world reshapes itself, luxury fashion seems ready for reinvention. How it’s made and sold, its role in people’s lives and culture, the creative director’s purpose—all of this will change. Something will replace spectacle, but what?

“We’re focusing on subtle techniques, and we like that—we like that people won’t fully grasp them from a photo,” says McCollough when I reconnect with him and Hernandez later in the summer. The collection is coming together, and late nights at the office are common. They often don’t get home until almost 11 p.m., McCollough says, “and then dinner is eggs” from the small market across from their new apartment. (Also in the 7th arrondissement, another short-term sublet—”still looking,” he explains.)

They love the 7th: its quiet, its openness, its small owner-run shops selling fish, wine, bread, and cheese. It’s livable, much like they want their evolving collection to be—balancing a sense of the moment with a feeling of authenticity. They talk about “softness,” “sensuality,” and “warmth”—words about feeling, not just seeing. Though they were once New York fashion darlings, Hernandez and McCollough never quite fit the spectacle era: a Proenza Schouler collection never shouted. Instead, it drew you in with nuance—a careful blend of cut, color, material, and construction that conveyed a distinct attitude.

“From the beginning, they had a very clear vision of what a cool woman’s wardrobe should be, and it was entirely their own,” says Sally Singer, president of Art + Commerce and former Vogue digital creative director. “Right now, I’d tell them: no one needs new clothes. If you pour everything into perfect ready-to-wear and expect people to buy head-to-toe looks, you’re stuck in the past. And I say this as someone who still wears their early striped tees—they’ve lasted.”

Singer was also on the CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund committee that awarded Proenza Schouler the first prize in 2004. She believed in them then, and she believes in them now.

“Their instincts are so strong—shoes, bags, red carpet, denim…”At Loewe, they can create an entire universe of items that make someone feel special—a bag charm, a candle, objects at every price point. Singer adds, “I think that’s the role of a creative director now: finding ways for people to connect with your brand, even when they aren’t making a purchase.”

On April 17, 2015, Hernandez and McCollough joined Singer for a talk at the Alliance Française in New York. When asked about the possibility of working for a luxury house, McCollough mentioned they’d been approached several times. While the resources were tempting, he said, “what matters most to us right now is Proenza Schouler.” Almost exactly ten years later, the two were on a plane to Paris, work visas in hand.

“It’s been an itch,” McCollough admits. Their label’s 20th anniversary passed, and they began to wonder: “Is this it? A life should have chapters—is this our only one? Of course, Proenza Schouler holds a special place in our hearts, but it’s all we’ve done since we were 19. Creatively, we started to feel like maybe we’d said everything we needed to say.”

Over two decades, Hernandez and McCollough built a strong identity for Proenza Schouler. Now, they’re curious to see how the new, yet-to-be-announced designer will evolve the brand. They remain on the board and are available “for questions,” McCollough notes. Otherwise, it’s a clean break.

“We’re very unsentimental,” Hernandez says.

“We’ve never even visited our own archive,” McCollough adds.

“But that’s fashion: What’s next?” Hernandez concludes.

They don’t feel homesick. They don’t even miss their friends, partly because they brought some to Paris to work with them, and many others keep passing through. My day with them at Loewe HQ ended with a visit to the Centre Pompidou for the preview of the Wolfgang Tillmans exhibition, where they met up with artist Nate Lowman—one of many friends in town for Art Basel. As we left the office, we coincidentally ran into an old friend of McCollough’s sister. “There’s always someone in Paris!” Hernandez exclaims.

It felt like Jack and Laz were trying to convince me to move here, too. Their commute home, they say, is a stroll through the Tuileries, and on these late summer evenings, they watch the sun set over the Seine as they cross the bridge to the Left Bank. Weekends are for art—or an hour’s flight takes them to London, the Alps, or St. Tropez. In two hours, they can be almost anywhere. The world is their oyster.

I pressed them: Don’t you miss anything?

They thought about it.

“If either of us were doing this alone, it would be different—scary,” McCollough says.

Hernandez nods emphatically. “Totally. What’s unique about us is that anywhere we go, if we’re together, we’re home.”

What’s interesting about Loewe is that it’s both LVMH’s oldest and youngest luxury brand. It started in 1846 as a collective of leather craftsmen in Madrid; Hermès is slightly older, but not by much. For most of its modern history, Loewe was a respected Spanish brand known for handbags and leather goods. Then Jonathan Anderson arrived in 2013 and transformed it into the playful, international luxury fashion house we know today. In that sense, Loewe is both 179 and 12 years old. Anyone succeeding Anderson had to embrace both its youthful, designer-driven energy and its deep Spanish heritage. According to Lepoivre, one reason Hernandez and McCollough stood out was their connection to that Spanish identity: “It’s something other designers haven’t known how to work with.”

Hernandez, whose family has roots in Spain, agrees that this aspect of the brand had been somewhat overlooked. “There’s a vibrancy and positivity in that culture that influences the brand’s vibe—it’s high fashion, but it’s fueled by that spirit.””There’s a note that’s missing,” he says. “A sense of the body—not sexiness, that’s something else entirely—but a sense of skin… I don’t know, just, Spanish-ness.”

“Solarity?” suggests McCollough. “Like sun, heat, but also dance, food. You’re welcomed—lots of hugging. It’s soulful.”

Once again, as we discussed their debut collection, I noticed Hernandez and McCollough speaking in terms of experience. Part of this was because they weren’t yet ready to reveal what the collection was shaping up to look like—keeping the “solarity” of their vibrant palette under wraps a little longer, for example. But I also believe it’s because they value tangibility.

Hernandez and McCollough are eager to discuss every centuries-old hand-stitching technique still used in Getafe and every high-tech leather treatment developed in the Loewe lab. What connects them to the brand—and what bridges old and new Loewe—is craftsmanship.

It’s tempting to say that fashion can be fixed by returning to artisanal methods—letting luxury be luxury, slowing things down. But that’s like saying better movies will fix Hollywood. Will they? People still have to go see them.

I’m not convinced that a change in leadership at major fashion houses alone can resolve this feeling of aimlessness, this endless-scroll sensation. Our technocapitalist society floods us with options—and the real challenge for creative directors today, I believe, is to figure out how to cut through that noise. People don’t want meaningless choices. Designers need to offer shoppers real decisions: products that inspire, that feel vital and new, and stir deep desire—not just a momentary pause before swiping to the next coat, bag, or shoe.

What does that take? My sense is that this moment calls for designers who dream big but stay grounded. Bold, distinctive visions, executed with skill and wearability in mind, so that when you touch their work, you understand it was made to be loved and to last. That’s when a luxury item feels worth its price.

Hernandez and McCollough may be exactly the right people for this task. When I met them, they were in a starry-eyed phase, testing the limits of their new studio.

“It’s like a big funhouse—playing around, seeing how far we can push things,” Hernandez said. A month later, though, playtime was winding down.

“Now we’re refining the collection, reining it in,” Hernandez tells me.

Americans in Paris. That practical approach might not only define Loewe’s next chapter but fashion’s path forward: the antidote to spectacle is authenticity.

“We want it to feel desirable,” McCollough says. “We want these to be clothes people can imagine living in.”

In this story: grooming by Jillian Halouska. Produced by AL Studio. Set Design by Mary Howard.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Americans in Paris Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez at Loewe designed to be clear and conversational

Beginner General Questions

Q Who are Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez

A They are the American fashion designers who founded the highly influential luxury brand Proenza Schouler

Q What is Loewe

A Loewe is a prestigious Spanish luxury fashion house known for its leather goods readytowear clothing and accessories Its owned by the LVMH group

Q What is the connection between these American designers and a Spanish brand

A In 2023 they were appointed as the new cocreative directors of Loewe taking over from Jonathan Anderson Its a major appointment in the fashion industry

Q Why is this such a big deal in fashion news

A Its rare for two established designers to leave their own successful brand to lead another heritage house It signals a significant new creative direction for Loewe

Advanced IndustryFocused Questions

Q What does their appointment mean for the future of Loewe

A It suggests a move towards a more structured architectural and perhaps more downtown NYC aesthetic blending with Loewes existing artisanal and artistic identity

Q How does their design philosophy at Proenza Schouler align with Loewes existing identity

A Both are known for intellectual designs expert tailoring and a modern sensibility Proenza Schoulers focus on deconstruction and art references fits well with Loewes artistic legacy under Anderson

Q What are the potential challenges they might face in this new role

A The main challenge will be stepping out of the long shadow of Jonathan Andersons highly celebrated tenure and establishing their own unique voice for the brand without alienating its existing customer base

Q Will they still be involved with Proenza Schouler

A No their move to Loewe was announced as an exclusive arrangement meaning they have fully departed from their roles at Proenza Schouler

Practical For Fans Questions

Q When will we see their first collection for Loewe