Every year when January 1 rolls around, people loudly declare that setting goals is pointless. But I secretly sit in a corner of my apartment, seriously filling out a spreadsheet to organize my resolutions for the year ahead. I don’t have any special love for spreadsheets, but the one advantage of writing everything down digitally is that reviewing my goals is as easy as opening Google Drive. Looking back at my objectives—which I do regularly—can be pretty funny. Eat more fiber; read Middlemarch; take self-defense classes. All very doable and specific. Yet there’s one goal that appears on every spreadsheet, untouched and mocking me with its constant neglect: Write a screenplay.

A little context might help—I’ll keep it short. I’ve been a journalist for many years and enjoy my work, but a couple of inspiring screenwriting classes in college, along with a love for TV and film, left me with a desire to tell cinematic stories. Despite taking an online screenwriting course with NYU Tisch a few years ago (which, in my opinion, was a waste of $2,283) and several failed attempts to get a script idea off the ground, years later I still don’t have even a logline. That’s the thing about creative pursuits—you have to actively work at them. Constantly. And eventually, it becomes clear that no one is going to push you to chase your dreams or reach your goals; the illusion of waiting for “the right time” gives way to the fear that time is running out.

I hit that point a few months ago while reviewing my goals for 2025. Staring once again at that empty spreadsheet cell, it was clearer than ever: either live with regret or push myself into action. I wish I could say my next move involved an enlightening talk with a wise mentor, but instead, I fell down a rabbit hole of YouTube videos promoting Ernest Hemingway’s writing routine. (Oh internet, you work in mysterious ways.) My first thoughts? One: Hemingway would have hated this. Two: I’m doing it anyway.

What started as a look into one iconic writer’s quirky habits quickly grew into exploring the routines of several literary giants. Would channeling these titans improve my chances of writing something worthwhile? The risk of ending up with nothing but mild embarrassment was real, but I decided my shortcomings could be reframed as growth—not so cringey after all. So if you’re also stuck in a creative rut, maybe give one of these ideas a try. Get your pencils and pads ready.

Truman Capote: Horizontal Writing

Picking up a fresh copy of Answered Prayers ahead of last year’s Feud: Capote vs. The Swans reminded me how delightful Truman Capote’s writing is. His sharp, gossipy style in that unfinished tell-all feels like joining the most glamorous (and catty) powder room conversation on the planet. In a 1957 interview with The Paris Review at his Brooklyn Heights home, he reflected on his writing habits: “I am a completely horizontal author. I can’t think unless I’m lying down, either in bed or stretched on a couch with a cigarette and coffee handy.” He’d puff and sip his way through coffee, mint tea, sherry, or martinis, writing everything by hand in pencil.

To start each day’s experiment, I’d read a bit or watch an interview of the writer, if available. I’m a sucker for Capote’s high-pitched Southern drawl, so I eagerly watched a clip of him telling Dick Cavett about taking intelligence tests as a kid. After that, it was off to the sofa.

My setup for the day included a large notepad, a Mono Graph mechanical pencil, and coffee.I started the day with tea, followed by fino sherry, and later a martini—gin with one olive. I skipped the cigarettes because I was staying in a rental in Paris, and smoking in someone else’s home felt rude. Although I’d had sciatica in the past and was cautious about back spasms, I was thrilled to spend the day lying on the sofa, writing and sipping drinks. The words came easily at first, and frequent coffee refills kept me alert. Looking back at my notebook from that day (10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.), I noticed a scribble in the margin: “my left foot is numb.” Other than that, it was productive. I loved writing by hand—and even more, I enjoyed slipping into another persona to push through creative block. The experiment left me energized and ready for the next character study the following morning—or so I thought.

Ernest Hemingway: One True Sentence

Photo: Kurt Hutton/Getty Images

I don’t idolize Hemingway, but who could resist reading A Moveable Feast and The Sun Also Rises during a two-month stay in Paris? Not me! At the time, I was living just a few blocks from his favorite spots—Brasserie Lipp, Les Deux Magots, and Café de Flore—so including him in my experiment felt fitting.

Anyone familiar with Hemingway knows he was obsessed with truth in writing. In his memoir, he talks about starting a story by writing “one true sentence”—the truest you know. He also emphasized rising early (just after dawn) and never draining your creative well completely: stop while there’s still something left, and let it refill overnight. As a bonus, I ended my afternoons at a nearby café, Hemingway-style (along with James Baldwin and Simone de Beauvoir), soaking up the creative vibe of Saint-Germain-des-Prés—even if these days it’s more tourists with €8 coffees than intellectual salons.

But staying up late binging Adolescence had predictable consequences. My first “true sentence” recorded before dawn was: “My eye sockets are sore.” After forcing myself to write a couple of uninspired pages, I fell asleep on the couch and was woken two hours later by my husband’s footsteps. Frailty, thy name is Nicole!

I started fresh the next day, better rested and far more productive. As expected, trying Hemingway’s routine in its Parisian setting was a delight.

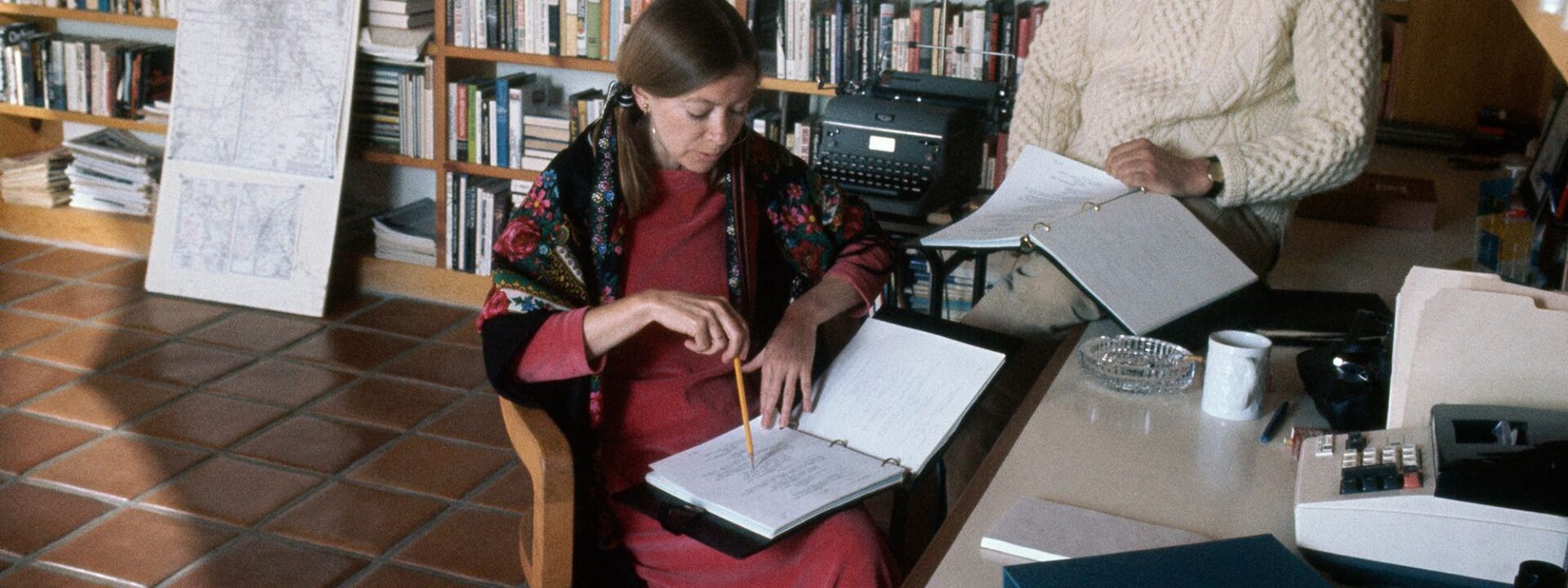

Joan Didion: Needlework

Photo: Getty Images

I was optimistic about adopting Joan Didion’s writing rituals. She’s one of my favorite writers (original, I know), and the idea of stepping into her routine was appealing. (Side note: I almost bought her needlework footstool at her estate sale a few years ago but was outbid. If the winner is reading this, it’s not too late to send it my way.)

Didion’s habits are well-known—her packing lists alone are legendary. If you’ve looked up her writing rituals, you’ve probably seen the quote about needing an hour alone before dinner, with a drink, to review the day’s pages. Spoiler: I do that. But I’m a bit obsessed and know her YouTube interviews by heart. In one, she mentions needlework as a way to work through creative block: “It’s sort of mindless. You do it when you’re panicking and trick yourself into thinking you’re doing something useful.”

So I found a local Parisian craft store and bought a petit point kit.I set a delicate lavender bouquet on the chair beside me and start working around 10 a.m. The story I’ve been struggling with feels flat, so I jot down in my notebook, “Is it too early to stitch?” I pick up the embroidery hoop and guide the pale purple thread through the fabric. There’s a special satisfaction in making something by hand. My mind drifts, and then a sense of clarity washes over me—all my thoughts seem to fall into place. It might sound silly, but it felt like a small revelation.

Charles Dickens: Three-Hour Stroll

Photo: John & Charles Watkins/Getty Images

Charles Dickens, the Victorian novelist behind classics like A Christmas Carol and Great Expectations, isn’t an author I revisit often. But when I learned about his daily routine, I was intrigued. He’d rise at 7 a.m., have breakfast around 8, then write alone in his study from 9 a.m. until 2 p.m. without a break. After lunch, he’d take a three-hour walk through London—every single day. How civilized!

Unfortunately, just as I finished my fifth hour of work, it started pouring. I grabbed an umbrella and kept going. Surprisingly, wandering through Paris in the rain with no agenda other than seeking inspiration turned out to be quite enjoyable. That afternoon, I took 21,219 steps, discovering a hidden church on Île Saint-Louis, browsing the riverside bookstalls, and exploring countless charming streets. By the end, I was tired but deeply satisfied. Dickens was onto something.

Haruki Murakami: 4:00 a.m. Wake-Up Call

Photo: Courtesy of Klim Publishers

Reading Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 during the Covid-19 lockdown is a fond memory. His magical realism offered a dreamlike escape from my cramped, gloomy apartment. But how does he create such surreal stories that lift us out of the ordinary?

“When I’m writing a novel, I wake at 4 a.m. and work for five to six hours. In the afternoon, I run 10 kilometers or swim 1,500 meters (or both), then read and listen to music. I go to bed at 9 p.m. I stick to this routine every day without change.”

In a 2004 interview, he emphasized that repetition is key. “It’s a form of mesmerism. I hypnotize myself to reach a deeper state of mind. But maintaining this for six months to a year requires mental and physical strength.” (As an aside, Murakami’s account of training for the New York Marathon is worth reading.)

Let’s be honest—I didn’t run six miles or swim 1,500 meters in the summer heat. While committed to this experiment, I’m not that committed, so I did a challenging workout video indoors instead. I did wake at 4 a.m., work for five hours, and get to bed by 9 p.m., which was more productive than I expected. My experiment wasn’t perfect—I couldn’t take a month off from paid work to fully adopt Murakami’s routine and benefit from repetition. But I accept my limitations calmly. After all, the goal was to see what resonated, to uncover rituals that might foster creativity over time. Here’s a glimpse of what I found.

The 10 Commandments of Creative Rituals

1. Begin before the world wakes.

2. Choose an environment that supports long periods of work.

3. Start simple, and stop before you’re drained.

4. Keep your hands busy.

5. Protect your focus—work alone.

6. Explore the world for ideas.

7. Make physical exercise a priority.

8. Reflect in the evening, maybe with a drink.

9. Get enough sleep.

10. Repetition is powerful.It’s a long way.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about I Tried the Creative Rituals of 5 Meticulous Authors Heres What I Learned

General Definition Questions

Q What is this article about

A Its a firstperson account of someone experimenting with the specific daily writing routines and habits of five famous highly disciplined authors to see what worked for them

Q Which five authors rituals were tried

A While the specific authors arent listed here meticulous authors often include figures like Haruki Murakami Maya Angelou Ernest Hemingway Stephen King and Virginia Woolf known for their strict routines

Q What exactly is a creative ritual

A A creative ritual is a consistent repeatable habit or routine that an artist uses to get into a focused productive state of mind Its like a warmup before the main work

Beginner Benefit Questions

Q Im not a professional writer Would trying this help me

A Absolutely The principles of routine focus and consistency can benefit anyone with a creative hobby a big project or even just a desire to be more productive

Q Whats the main benefit of having a creative ritual

A It reduces the mental effort needed to start It tells your brain Its time to work now making it easier to overcome procrastination and access a creative flow state

Q Do I need a lot of time for a ritual to work

A Not at all Rituals can be very shortlike a fiveminute meditation making a specific cup of tea or organizing your desk The key is consistency not duration

Practical Application Tips

Q How do I find a ritual that works for me

A Experiment Start small by borrowing elements from authors you admire Pay attention to what conditions make you feel focused and calm then build a simple routine around that

Q Whats a simple ritual I can try today

A Try the Murakamiinspired ritual Wake up early write for a set amount of time before doing anything else then immediately reward yourself with exercise like a walk or run

Q What if my schedule is too unpredictable for a strict routine

A Focus on microrituals instead