If patience is a virtue, then artist Elisheva Biernoff must be among the most virtuous. Her painting technique demands an extraordinary level of focus. Using old photographs of strangers, which she finds on eBay and in antique stores, she meticulously recreates the images at their exact original size—front and back—with tiny brushstrokes on paper-thin plywood. She works on only one painting at a time, and each takes three to four months to finish.

“They’re kind of… all-consuming,” says Biernoff, 45, who is based in San Francisco. She completes just a handful of paintings each year. “I like living with one of them, having that bond.”

Biernoff developed her unique approach out of a love for other people’s photographs, an interest that began during her time at Yale University, where she was pre-med while also studying art. (“I thought I could be a doctor who made art,” she says. A difficult organic chemistry class convinced her otherwise, and art won out.)

In 2009, the year she earned her MFA from the California College of the Arts, she was invited to design a window display for the San Francisco Art Commission’s Art in Storefronts initiative. Biernoff asked people in the neighborhood to submit family photos, which she then replicated in paint for her installation. The result resembled a community living room wall, filled with the intimacy of a photo album but elevated by the intense attention her painting process requires. Creating art in this way connected her to people and places she otherwise wouldn’t have known. She was hooked.

Since then, she has had solo shows in California, Nevada, and Canada. Now she can add New York to that list, with the recent opening of “Elsewhere,” her first solo exhibition on the East Coast, held at the David Zwirner gallery’s elegant Upper East Side townhouse—a fitting setting for artworks based on family photos.

The show acts as a mini-retrospective, featuring 27 works from 2011 to 2025. Alongside the paintings of old photographs is a newer piece called Road Not Taken (2024), Biernoff’s recent exploration of trompe l’oeil. Its nine component paintings resemble paint-by-number kits—what Biernoff calls “living room art”—but in fact, each has been meticulously hand-painted. Even the wood grain on the frames is the artist’s own work.

The majority of her photo-based paintings are small—some just four inches tall—yet they speak volumes about memory, empathy, and what it means to look closely. Biernoff doesn’t use a magnifying glass, making the details she replicates, like the two dozen holiday cards in Advent (2025), all the more impressive. “I feel like I squint a lot, and hunch a lot,” she tells me as we walk through the gallery. She uses the smallest brushes she can find.

The gap between the moment the original photo was taken and the time spent recreating it is vast, and within that gap lies the magic. “These images have a way of opening up the longer I spend with them,” Biernoff says. Small details emerge, like a grandparent’s hand in the corner of Generation (2014–2015), or a Bible verse written on a bulletin board in Beyond Our (2023). These hidden discoveries can deepen, or even completely change, the meaning of the painting.

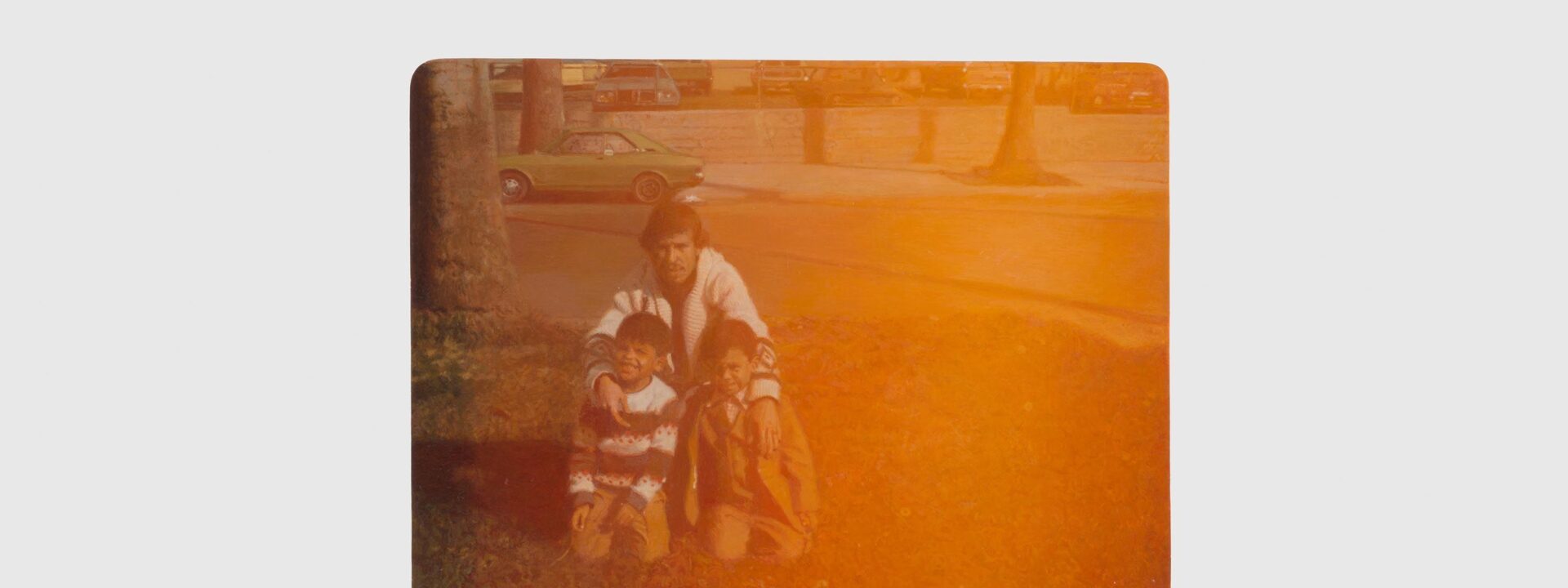

For the most part, Biernoff works with photographs taken from the 1950s through the 1980s—eras when cameras were reserved for special occasions, unlike today, when taking a picture is as simple as pulling out a phone. The photos from that time carry a certain weight. They also have a distinct palette, muted and softened with the patina of time. Biernoff’s work feels more nostalgic than the slick, polished images of our digital age.Consider photorealistic paintings by artists like Audrey Flack or Richard Estes. Though from a different era, the photographs Elisheva Biernoff selects capture everyday scenes that still feel familiar: someone on a couch reading the paper, children playing outside. Yet, because these are images of strangers, their full stories remain hidden. In Strike (2021), which shows a jagged tree stump before a white house, the only hint is an inscription on the photo’s back, which Biernoff also reproduces: “Smashed up house after the storm. July 1970.” But what storm, and where? “I’m interested in how they remain ciphers,” she says. “I can invent stories or project my feelings onto them, but they are ultimately unknowable.”

While Biernoff’s work deals with time, it is equally about control—or the illusion of it. “Most of us try to look good in photos, right? We control the outcome through how we dress, pose, or edit. But I’m always drawn to pictures where something unintended happens,” she explains. Scrolling eBay or browsing vintage shops, she seeks out quirks: a slipped hand, a flash reflecting off a mirror, a chemical mishap in development. Biernoff replicates these flaws with the same precision and respect as any other part of the image. “They’re affirmations of humanity. It’s life in the moment, not life idealized.”

Biernoff also inserts her own interventions. In the assemblage Fragment (2024), she recreates a 1950s postcard collected by her grandmother-in-law, “tacked” (with a handmade ceramic pushpin) against “wood paneling” (hand-painted plywood). The postcard depicts a 12th-century carved lintel fragment from the Cathedral of Saint Lazarus in Autun, France, showing Eve reaching for the forbidden apple. The original carving was removed from the church, lost in the 18th century, later found as building material for a house, then restored and moved to Autun’s Musée Rolin, where it remains.

“I loved how that echoed Eve’s story of displacement—banished for taking the fruit,” Biernoff says. In that spirit of expulsion, she painted two lighter rectangular patches in the wood grain beside the postcard, like ghosts of missing postcards.

The back of the Eve postcard isn’t visible, but Biernoff painted it as well—an imaginary note from Eve’s perspective, addressed to Polish poet Wisława Szymborska, tracing the lintel’s journey: “By a wonder, I was salvaged, then sold, scrubbed, and spotlit. Do you call that resurrection or exile?”

Perhaps it is a rebirth—for this stone Eve, and for all the anonymous figures in Biernoff’s paintings. They all receive an afterlife, whoever they were.

“Elisheva Biernoff: Elsewhere” is on view at David Zwirner, 34 East 69th Street in New York City, through February 28, 2026.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs In Elisheva Biernoffs Paintings a Picture Takes Two Thousand Hours

Q Who is Elisheva Biernoff

A Elisheva Biernoff is a contemporary visual artist based in San Francisco known for her incredibly detailed timeintensive paintings that explore themes of memory perception and the natural world

Q What does it mean that a picture takes two thousand hours

A Its a literal description of her process Biernoff spends an astonishing amount of timeoften around 2000 hours or moreon a single smallscale painting applying countless layers of translucent oil paint to build up depth and detail

Q Why does it take so long to make one painting

A Her technique is extremely meticulous She works in thin glazed layers of oil paint allowing each layer to dry completely before adding the next This slow meditative process creates a unique luminous quality and a deep sense of space that cant be achieved quickly

Q What kind of subjects does she paint

A She often paints serene intimate landscapes and natural scenes like forest interiors meadows or bodies of water These are usually based on photographs but are transformed through her painstaking process into something dreamlike and deeply textured

Q Whats the benefit of spending so much time on one piece

A The immense time investment allows for an extraordinary depth of color light and detail It creates a powerful almost immersive viewing experience where the painting seems to hold time itself encouraging slow contemplative looking from the viewer

Q How big are these paintings that take 2000 hours

A Ironically they are often quite small sometimes just a few inches across The scale contrasts with the monumental time investment making the viewer lean in and engage closely with the intricate surface

Q Is this considered slow art

A Yes absolutely Biernoffs work is a prime example of the slow art movement which is a reaction to fastpaced culture It emphasizes deep focus craftsmanship and an artistic process where time is a primary material

Q Whats a common challenge or problem with this method

A The main challenge is the sheer physical and mental endurance required It demands incredible patience a steady hand and a longterm vision as