“A Garden of American History at the White House” by Valentine Lawford first appeared in Vogue‘s February 1967 issue.

For more highlights from Vogue‘s archives, subscribe to our Nostalgia newsletter [here].

The White House’s first true formal flower gardens—the Rose Garden and the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden—were redesigned under President Kennedy, who eagerly followed their progress. Now, Mrs. Johnson tends to them as they flourish. The Rose Garden is lined with crab apple trees and bursts with chrysanthemums in autumn, while magnolia trees planted by Kennedy grace each corner. The Jacqueline Kennedy Garden features sculpted hollies amid blue-grey dusty miller and herbs, leading to a grape arbor where Mrs. Johnson enjoys serving tea on pleasant days, surrounded by the scents of rosemary, thyme, and fresh-cut grass.

“Though the times are filled with political events, I shall say nothing on that or any subject but the innocent ones of botany and friendship…”

These words, written by Thomas Jefferson in 1803 from the White House to General Lafayette’s aunt in France, accompanied a shipment of American plants and seeds—magnolia, sassafras, tulip-poplar, dogwood, and several oaks and roses.

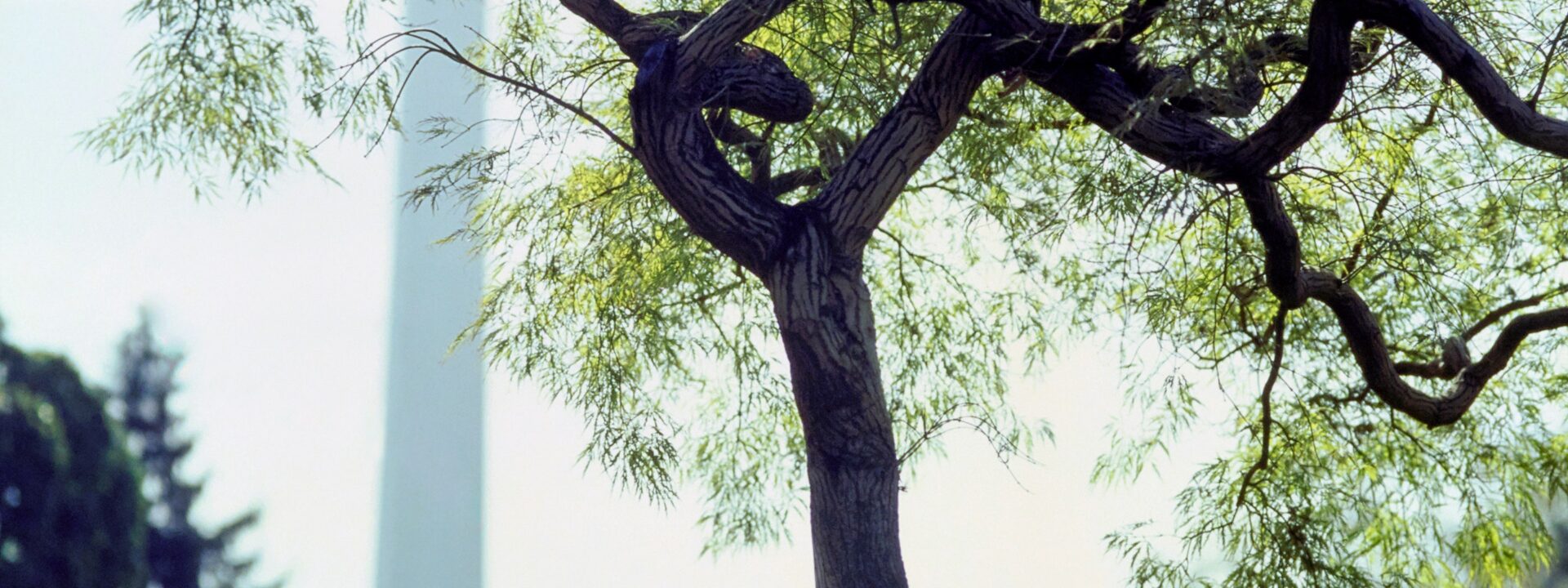

The South Grounds of the White House in Washington, D.C., still bear traces of Jefferson’s influence, including two mounds from his presidency. A commemorative American elm planted by John Quincy Adams stands in the distance, while a willow oak added by President Lyndon B. Johnson grows on the far right.

Photographed by Horst P. Horst. Vogue, February 1967

Jefferson’s letters evoke a bygone era of unhurried elegance in American leadership. Yet his words remain a fitting guide for describing the White House gardens—both as they were and as they are today.

President Kennedy, deeply rooted in Jefferson’s ideals, transformed the White House grounds during his short tenure, creating its first proper flower gardens. First Lady Lady Bird Johnson has carried on this legacy, championing beautification efforts in Washington and nationwide, embodying Jefferson’s belief that national pride and natural beauty go hand in hand.

First Lady Mrs. Lyndon B. Johnson (Lady Bird) stands beside the commemorative American elm planted by John Quincy Adams on the White House grounds.

Photographed by Horst P. Horst. Vogue, February 1967

Of all gardens, the White House’s reveals its secrets reluctantly. Though it belongs to the nation, it has been shaped by nearly three dozen presidents and their families over its 150-year history. Each left their mark—sometimes for better, sometimes worse—but always mindful of their duty to future occupants.

Yet its official role lends the garden a unique poignancy, rare in private landscapes.The White House gardens. You can sense how little time most presidents have had to spend here, and how precious those rare moments of full enjoyment must have been. At first glance, the space seems impersonal, but this soon gives way to a surprising curiosity about even the most obscure former presidents.

[Photo: The South Portico of the White House in Washington DC, photographed by Horst P. Horst for Vogue, February 1967]

The garden’s history isn’t thoroughly documented, with significant gaps in 19th-century records. Fortunately, current White House Curator James R. Ketchum has gathered every available detail, while Irvin Williams of the National Park Service has kept a diary tracking recent changes. The Park Service has also created a map identifying all 500+ trees on the grounds, including about 30 confirmed to have been planted by presidents. With this guide, walking through the grounds feels less like visiting a park and more like exploring a living museum where historical figures have been transformed into the very landscape.

George Washington, an avid gardener, selected the White House site during a 1790 survey with architect L’Enfant. Though he never planted here himself, several trees in the South Grounds today descend from his hardy orange trees at Mount Vernon.

[Photo: White House gardens featuring a Pine Oak planted by President Dwight Eisenhower, photographed by Horst P. Horst for Vogue, February 1967]

John and Abigail Adams were the first presidential residents, moving into the unfinished building. Despite the challenges, Abigail admitted the location was beautiful. The grounds were first fenced during Adams’ presidency, but it was Jefferson who began landscaping in earnest—planting trees, creating paths, and even building two small hills (still called Jefferson’s Mounds) to provide privacy from public view. These mounds add welcome variety to what would otherwise be flat, exposed land.

Funding was always an issue. For years, the grounds were pockmarked with clay pits from brick-making for the House. In 1805, future president James Monroe politely complained about these hazards, while a British visitor in 1807 was more blunt, calling the neglected grounds “a disgrace to the country.” Ironically, British troops later worsened the damage during their 1814 attack on Washington, nearly burning the White House completely. Contemporary images show the damaged mansion standing forlornly among sparse young trees.

[Photo: A White Oak planted by Herbert Hoover at the White House, photographed by Horst P. Horst for Vogue, February 1967]

[Photo: An American Boxwood planted by Harry Truman at the White House North Portico, photographed by Horst P. Horst for Vogue, February 1967]After the war ended, the barren landscape of the White House grounds gradually transformed into a place of beauty. In the 1820s, as shown in a lovely sketch by Latrobe, neat rows of flowers lined the path to the South Portico. A later engraving reveals simple garden designs, a curved fence, and sheep grazing on the lawn.

The Darlington Oak was planted by Lyndon Johnson with his collie Blanco on the White House grounds in Washington, D.C. (Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, February 1967).

President Jefferson began planting trees on the mounds during his time in office, but the oldest surviving documented tree is an American elm planted by John Quincy Adams between 1825 and 1829 on the eastern mound. This tree remains a centerpiece of the grounds, drawing admiration and attention. Even if one barely remembers Adams’ other accomplishments, his tree alone makes a strong case for his legacy. It’s delightful to know he enjoyed picking berries, cut the White House hay himself, and swam in Tiber Creek at the edge of the property.

Adams’ successor, Andrew Jackson, planted two Southern magnolias near the South Portico in memory of his wife, who had died soon after his election—reportedly from grief over the harsh campaign. Birds fill their branches with song, and two garden benches sit beneath their shade. Sitting there, one might imagine being a guest at an old Southern estate, though the striking contrast of the dark leaves against the bright sky and white columns brings to mind a Matisse cutout.

After Jackson, there’s little record of gardening activity under Presidents Van Buren, Harrison, Tyler, Polk, or Taylor (1837–1850). No significant landscaping changes from their time have been discovered.

The North Portico of the White House, framed by American boxwoods planted in honor of Harry Truman (Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, February 1967).

Surprisingly, it’s Millard Fillmore—often overlooked—who made the next notable horticultural contribution. He hired A.J. Downing, America’s first professional landscape architect, to redesign the grounds in the Romantic (or “English”) style. Downing proposed planting trees along the south vista and encircling the South Lawn with a ring of trees. Though most of his plans weren’t carried out, some of his work remains.

The late 1800s saw a revival of commemorative plantings. Rutherford Hayes planted an elm near the North Portico, Benjamin Harrison added scarlet oaks by the Pennsylvania Avenue gates, and Grover Cleveland’s wife planted delicate Japanese maples near the South Grounds fountain—a charming late-century touch.

Like in Europe, greenhouses flourished during this era. The White House likely had one from early on, but the first documented greenhouse appeared in 1857. After a fire in 1867, it was rebuilt and became famous for supplying flowers for increasingly lavish events.

A close-up of the South Portico, framed by Andrew Jackson’s magnolia tree (Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, February 1967).

As Julia Grant later recalled, “Life at the White House was a garden of orchids.”In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison commissioned designs for a massive new conservatory on the South Lawn. Inspired by a mix of the Brighton Pavilion and the Crystal Palace, this grand glass structure would have stretched the full length of the White House—if it had been approved, which it wasn’t. Instead, the First Lady focused on redecorating the mansion’s interior, filling the upstairs red velvet hallway with potted ferns.

Years later, President Theodore Roosevelt removed the greenhouse entirely. On its former site, he began construction of the new Executive Wing, including the current Oval Office—a single-story building with its own charm that still complements the original 19th-century structure it extends to the west.

A portrait in the White House’s Green Room shows Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt seated on a garden bench near the South Portico, surrounded by lush rhododendrons. She is credited with the first recorded design for the East Garden. However, in those days, the White House grounds were better known for their animals than their plants.

From Jefferson’s mockingbirds to Lincoln’s goats, Caroline Kennedy’s pony Macaroni, and the current president’s collie and beagles, the White House has always had famous pets. But during the Roosevelt children’s time, the grounds resembled a small zoo.

Under Woodrow Wilson, sheep briefly grazed the South Lawn as part of the World War I effort. After the war, Wilson planted an elm in the North Grounds, starting a tradition of commemorative tree-planting that continues today.

In the 1920s, Mrs. Harding planted a magnolia near East Executive Avenue, while the Coolidge administration’s white birch was placed at the far end of the South Grounds. Later presidents, however, focused their plantings near the West Executive Avenue, Jefferson’s western mound, and the Oval Office—perhaps wanting something beautiful and personal to admire from their windows.

Today, this corner of the grounds holds a special charm for visitors. A sturdy white oak planted by Herbert Hoover stands beside a little-leaf linden from Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. Truman reportedly played horseshoes near the linden, while Eisenhower’s contributions include a pin oak and a black walnut—his putting green’s faint outline still visible in the grass.

Nearby, a Japanese white tree-lilac marks where the Kennedy children once played, with their sandpit, treehouse, slide, and swing. Closest to the Oval Office is one of four Magnolia soulangeana trees planted by President Kennedy in his redesigned Rose Garden. The most recent additions are President Johnson’s plantings.

(Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, February 1967)During Franklin Roosevelt’s first term as president, he hired a renowned landscape architecture firm to assess the White House grounds and document its historic trees. While global events delayed major changes at the time, many of their recommendations were later implemented by subsequent administrations to great effect.

The landscape architects suggested replacing short-lived silver maples and overgrown conifers with mature, long-lasting trees. They also noted the poor quality of the lawn and criticized the flower gardens as underwhelming, calling for more vibrant and carefully designed floral displays.

The Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, named by First Lady Lady Bird Johnson in 1965, features rows of topiary hollies set in squares of dusty miller plants, surrounded by yellow flowers and fragrant herbs like rosemary and thyme. A neatly trimmed lawn leads to a grape arbor where Mrs. Johnson enjoyed hosting tea gatherings.

Years later, President John F. Kennedy reviewed the original landscape report. Though not an experienced gardener himself, he recognized the garden’s potential. After visiting European leaders, he felt the White House grounds fell short of what the U.S. presidency deserved. Kennedy believed beautiful gardens could positively influence diplomatic discussions and that a president deserved inspiring surroundings for reflection.

Early in his presidency, Kennedy enlisted a gardening expert to help redesign the Rose Garden near the West Wing and its counterpart, then called the East Garden. He wanted botanically significant plants, avoiding clichés like magenta azaleas, and preferred flowers that would have been familiar to Washington and Jefferson. The redesigned Rose Garden, inspired by 18th-century American gardening styles, required extensive work—including digging four feet down through Civil War-era rubble. During construction, workers accidentally severed the White House’s main power cable, prompting an emergency replacement.

Kennedy took a hands-on approach, often visiting the garden after late-night work sessions to check on progress. He paid close attention to every detail, showing particular impatience to see the project completed. His vision extended beyond just the flower gardens to the entire grounds as a cohesive whole.President Kennedy took great pride in the White House gardens, planting numerous trees—including citrus, apple, and deodar—that, while not officially marked as memorials, still served as living tributes. The lawns were his particular passion. If rain had left the grass damp or struggling, events would be moved indoors to the East Room or to the lawn south of the Oval Office. Even when Sir Winston Churchill received honorary American citizenship on the Rose Garden lawn, Kennedy first made sure the grass was in perfect condition.

Just outside the Oval Office window, a carefully designed planting showcases his horticultural vision. A Magnolia soulangeana stands at the center, surrounded by artemisia, with layered borders of hosta, epimedium, and Sedum Sieboldii. The magnolia was chosen not just for its spring blossoms but for the striking silhouette of its bare winter branches. The artemisia’s silvery leaves highlight the hosta’s summer blooms, while the sedum adds rosy autumn color. In spring, scillas fill the gaps with delicate blue flowers.

Lady Bird Johnson, First Lady to President Lyndon B. Johnson, is pictured in the Rose Garden wearing a green double-breasted coat with black buttons, gloves, and shoes. Behind her, chrysanthemums bloom in vibrant colors, and in one corner stands one of the four magnolias planted by Kennedy.

The gardens are structured with greenery as their foundation—grey-foliaged plants and boxwoods provide subtle texture among the flowers. Herbs like thyme, rosemary, and basil mingle with the blooms, keeping the scale intimate rather than grand.

Two rows of five low-growing trees frame each garden’s central lawn—crab apples in the Rose Garden and topiary hollies, reminiscent of those at Williamsburg’s Governor’s Palace, in the East Garden.

In spring, tulip beds in the Rose Garden are edged with grape hyacinths like a blue ribbon, replaced by heliotrope in summer. The roses include old-fashioned striped varieties, rugosas, ramblers, and the white “John F. Kennedy” rose. By autumn, chrysanthemums bloom among the last roses, and scarlet hawthorn berries glow near the South Portico.

The East Garden, replanted after the Rose Garden’s completion, features eighteen square beds fragrant with spring jonquils and bluebells. Summer brings heliotrope, petunias, and red dianthus (a favorite of Mrs. Kennedy), followed by blue asters and “Rajah” chrysanthemums in fall.

A Japanese maple, planted by First Lady Frances Cleveland, stands on the grounds with the South Lawn’s fountain visible behind it.

At the garden’s west end, a white wooden arbor draped with Concord grape vines offers the First Lady—traditionally the garden’s steward—a peaceful retreat with a view that is…The gardens are subtly colorful rather than dazzling, with a design inspired by 18th-century American layouts, much like the Rose Garden. They also evoke the charm of a French jardin de curé or a quaint medieval English castle garden. Like the remarkable man who played a key role in their revival, both White House flower gardens leave a lasting impression.

Though President Johnson never claimed to be a gardening expert, he enjoyed showing visitors around his personal garden in Northwest Washington during his Senate years. Now, he occasionally finds time to appreciate the White House gardens when his schedule allows. But it’s Mrs. Johnson who takes the most active and personal interest in the trees and flowers. She frequently tours the grounds with the Head Gardener, taking great care in their upkeep. The National Park Service knows her well—she strongly opposes removing any White House tree, no matter how aged or damaged. (If a tree must be cut down, the gardeners usually wait until she’s out of town.)

Mrs. Johnson has always loved gardening. She made sure to learn about the White House gardens and their blooms, just as she tends to her own garden in Texas. She’s passionate about preserving Texas wildflowers and establishing roadside parks in her home state. Known for favoring bright, cheerful flowers, her favorites reportedly include gaillardias, Rudbeckia gloriosa, zinnias, geraniums, and marigolds—all vibrant, sun-loving blooms.

The Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, named by Lady Bird Johnson in 1965, features neatly trimmed topiary hollies set in squares of blue-gray dusty miller, surrounded by yellow flowers and fragrant herbs like rosemary and thyme. A long, manicured lawn leads to a grape arbor, where Mrs. Johnson often serves tea.

She enjoys spending time in the garden, entertaining friends and sometimes surprising the gardeners as they work. Practical and attentive, she cares as much about the lawn’s condition as the trees and flowers. Thanks to her persistence, the long-standing issue of maintaining the lawn may finally be resolved.

Deeply committed to preserving the garden’s historical integrity, she ensures nothing compromises its legacy. Shortly after becoming First Lady, she asked a friend of President Kennedy—who had helped redesign the gardens—to continue his work under the new administration. Their collaboration has been fruitful ever since.

Most notably, Mrs. Johnson honored her predecessor by securing Congressional approval to rename the East Garden the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, dedicating it in the first spring of the Johnson administration. Future historians may see this as a gesture of political continuity, but gardeners and admirers recognize it as a simple, graceful act of respect.

(Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, February 1967)