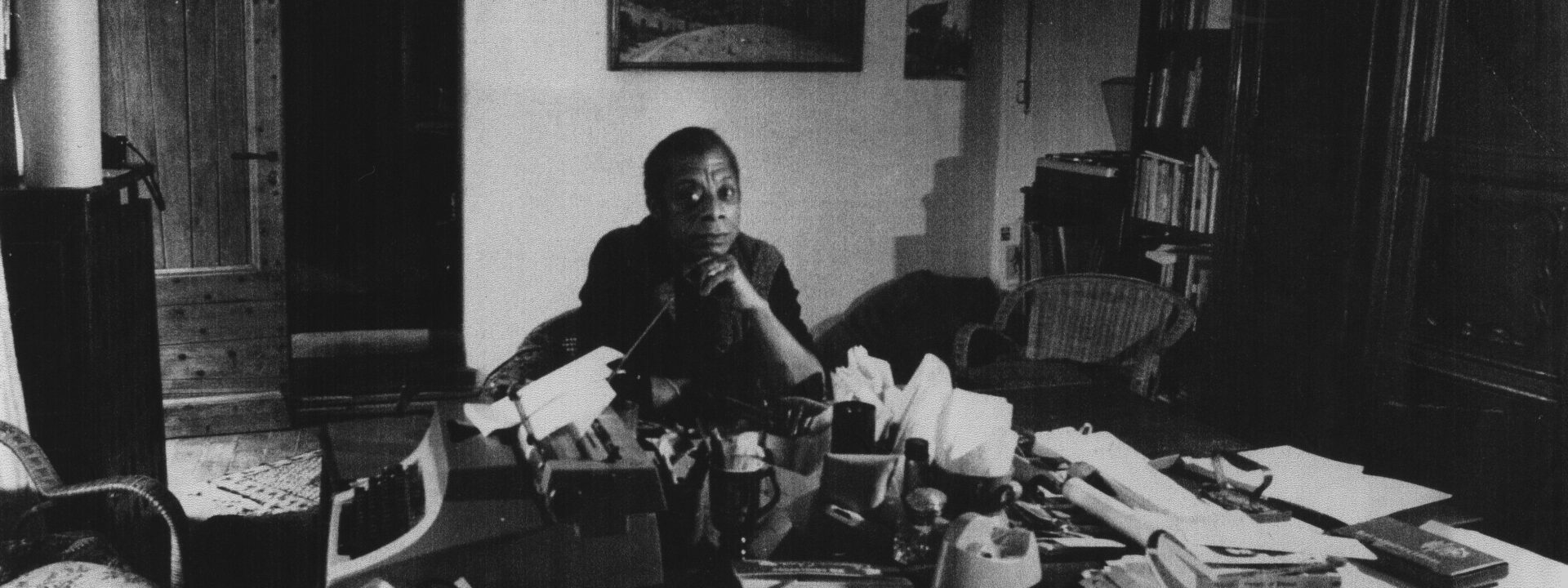

In 1996, during my junior year of college, I took a James Baldwin course where we read nearly everything he’d written—his groundbreaking novels, controversial plays, and celebrated essays. Everything except one book my professor briefly mentioned: Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood, a children’s book published in the UK in 1976 but now out of print. Curious, I checked David Leeming’s recent Baldwin biography and found only a short paragraph about it, mentioning an obscure French artist named Yoran Cazac, who illustrated the book. Leeming called their connection a “friendship,” but the next lines hinted at something deeper: “Yoran was not a solution to Baldwin’s need for a lasting relationship. He was committed to his family and lived mostly in Italy.”

The details only made me more intrigued. Leeming wrote that when Baldwin traveled to Italy to be godfather to Yoran’s third child, it must have reminded him of another friend, another marriage, and another baptism in Switzerland in 1952. Baldwin later dedicated If Beale Street Could Talk to Yoran, just as he had dedicated Giovanni’s Room to Lucien.

I knew “Lucien” was Lucien Happersberger, the Swiss man Baldwin once called the love of his life. Giovanni’s Room, his classic 1956 novel about a closeted American’s affair with an Italian man in Paris, was the first Baldwin book I’d read—back in ninth grade. I’d secretly borrowed my twin sister’s copy, hiding it under my mattress, afraid my family would see it and guess I was gay—something I wasn’t ready to admit even to myself.

Now, in college, recovering from my own secret relationship with another man, I was finally coming out—and Baldwin was my guide. How had he navigated heartbreak and his identity as a man who loved men? And how had that shaped him as a writer? That was what I wanted to be, too.

Soon, I visited the Beinecke Rare Book Library, which had a copy of Little Man, Little Man. Holding it for the first time sent a jolt through me, like when I first opened Giovanni’s Room. With its large text and bright illustrations, it looked like a children’s book, but the jacket called it “a children’s book for adults.” Instead of author photos, Cazac had drawn himself painting Baldwin, both smiling at each other, Baldwin with a cigarette.

I sent one of my first-ever emails (a novelty at the time) to David Leeming, who taught nearby at the University of Connecticut, asking if he knew more about Yoran Cazac. He replied politely, saying he’d never met Cazac, didn’t know anyone who had, and believed Cazac was likely no longer alive.

Seven years later, after graduating and moving to New York for my PhD at Columbia, I decided to write to art historians in Paris, hoping they might know more.I had been researching a deceased and relatively unknown artist named Yoran Cazac when, a few months later, my phone rang in my Brooklyn apartment. A raspy voice with a strong French accent said, “This is Yoran Cazac, calling from Paris. I hear you’ve been looking for me.”

It felt like hearing from beyond the grave. He invited me to Paris to see an exhibition of his work and meet him in person. “I have many stories to tell you about Jimmy,” he said.

I didn’t hesitate—I signed up for a third credit card and booked the cheapest flight to France I could find.

That call set me on a journey that would span over twenty years, taking me from New York to Paris, Tuscany, the south of France, Corsica, and eventually Turkey. I was searching for the truth about Baldwin’s most enduring intimate and artistic relationships with men: Lucien Happersberger, Yoran Cazac, the Black gay painter Beauford Delaney (who became Baldwin’s lifelong mentor), and the Turkish actor Engin Cezzar, whom Baldwin followed to Istanbul in the early 1960s. It was there that Baldwin finished Another Country (1962) and The Fire Next Time (1963).

The call from Cazac also marked the beginning of my effort to revive Little Man, Little Man, which finally happened in 2018—22 years after I first read it. Around the same time, I signed my first book contract to write a biography of James Baldwin. But the path ahead wasn’t simple.

One major challenge was how to write about Baldwin’s relationships, which defied easy labels. As Baldwin once said in an interview, “The men who were my lovers—well, the word ‘gay’ wouldn’t have meant anything to them.” He was often drawn to men like Cazac, who were primarily attracted to women and frequently married to them. (Happersberger, for example, later married Black actress Diana Sands, beginning an affair with her during rehearsals for Baldwin’s play Blues for Mister Charlie.) The same was true of Cezzar, who played Giovanni in a workshop production of Giovanni’s Room before returning to Istanbul and marrying actress Gülriz Sururi—who became a close friend and confidante of Baldwin’s. As for Delaney, who was over two decades older, he had fallen in love with Baldwin when they first met in Greenwich Village. Baldwin was just 16, but Delaney accepted the role of his “spiritual father.”

None of these relationships fit neatly into conventional categories, yet they sustained Baldwin throughout his life. They shaped his art, offered him refuge from the pressures of the civil rights movement, and gave him a sense of belonging across continents.

In “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” part of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin wrote, “If love will not swing open the gates, no other will or power can.” All of his novels are, in a sense, love stories—from John’s adolescent longing for Elisha in Go Tell It On the Mountain (1952) to Giovanni’s Room and Another Country. Even If Beale Street Could Talk (1973), a Black heterosexual love story set in Harlem, drew inspiration from Baldwin’s relationship with Cazac, to whom he dedicated the book. Through my conversations with Cazac, I came to understand that he wasn’t just Baldwin’s friend—he was his last great love.The forces that separated Tish and Fonny stemmed from the racism of the justice system—Fonny was wrongly imprisoned on false charges. In contrast, the divide between Baldwin and Cazac was more personal and cultural. Yet Tish’s words perfectly express Baldwin’s feelings about his eventual parting from Cazac: “I hope nobody has to look at anybody they love through glass.”

As it turned out, love was Baldwin’s greatest theme. By the end of my journey with Baldwin, these became the closing lines of my book: “It wasn’t until near the end of this voyage that I realized what I’d truly been researching and writing all along—a new biography of James Baldwin. But from the start, I always knew it was a love story.”

Baldwin: A Love Story

$33 | BOOKSHOP

Nicholas Boggs’s Baldwin: A Love Story will be released on August 19.