Hari Nef graciously met with me on a Thursday afternoon to discuss the new exhibition honoring Candy Darling—the iconic late actress, diarist, and cultural legend—now on display at photographer Ethan James Green’s New York Life Gallery (running through May 31). Titled Pieces of Candy: 10 Artists Celebrate Candy Darling, the installation features works by Drake Carr, Connie Fleming, Jimmy Paul, Lorena Pain, Kabuki Starshine, Sunny Suits, Billy Sullivan, Tabboo!, Elliot Vera, and Jimmy Wright, all housed in two glass cases. Most were created for the 15th-anniversary issue of Luis Venegas’s C☆NDY magazine, except for Tabboo!’s piece, which dates back to 2005.

“I can’t think of anyone but Ethan, or any other space, that would not only celebrate C☆NDY in an art-world context but also spotlight these particular artists’ perspectives,” Nef said. “This feels fresher and more urgent than the familiar, beloved portrayals of Candy. Huge credit to Ethan and Luis for crafting a world where boundary-defying beauty is celebrated—and in a magazine named after Candy, because who else could it possibly be named after?”

Nef—who appears in the latest issue of C☆NDY—brings both a deeply personal and professional connection to the project. She’s currently developing a film about Darling, whom she’ll also portray. Darling’s cultural impact has never been more relevant, making Nef’s film especially timely. A luminous figure of the late ’60s and early ’70s Warhol Factory scene, Darling was a transgender pioneer on the verge of a breakthrough acting career before her death at 29 in 1974. In today’s world, both this exhibition and Nef’s upcoming film underscore the importance of remembering and honoring her legacy.

Vogue: Hari, when did you first discover Candy—and what are your earliest memories of her?

Hari Nef: I likely first came across Candy on Tumblr. Before that, I saw fashion, art, and film as separate worlds, but Tumblr blurred those lines. It was also when identity politics, as we now understand it, began taking shape online—where academic ideas and theories got distilled into internet discourse. For me, Tumblr was where the concept of a trans history or archive started to form.

There were these mesmerizing images of Candy Darling—so striking, so glamorous—that fit right alongside Steven Meisel photos and Antonioni film stills I was obsessed with. Here was this woman who looked like a classic Hollywood star, but then you learn she was trans and part of Warhol’s circle. I’d devoured everything about Warhol in high school—books, even Factory Girl when it came out. I knew about Edie Sedgwick and that whole scene, which felt like the birthplace of so much I considered (and still consider) “cool.” But realizing there was a trans woman in that world—someone so stunning, so revered, who left behind diaries echoing the same thoughts and struggles me and other trans girls were grappling with—was revelatory. Beyond the images, if you looked deeper, there she was.A woman who spoke to us from the past, 50 years before any of us were born. She had her own power, making films with legends like Warhol—and others, too: Werner Schroeter, Alan J. Pakula (she had a small role in his 1971 film Klute), and even starred in a Tennessee Williams play.

Which Tennessee Williams play?

She played a minor role in his early ’70s play Small Craft Warnings, as a troubled woman in a bar. She took over the part after the original actress—a cisgender woman—dropped out. Tennessee adored her; he was captivated by her presence, though his decision caused tension. The other actresses refused to share a dressing room with her, forcing her to change in a closet—she even put a star on it. The woman she replaced was furious about being swapped out for a trans woman and made a scene, eventually reclaiming the role.

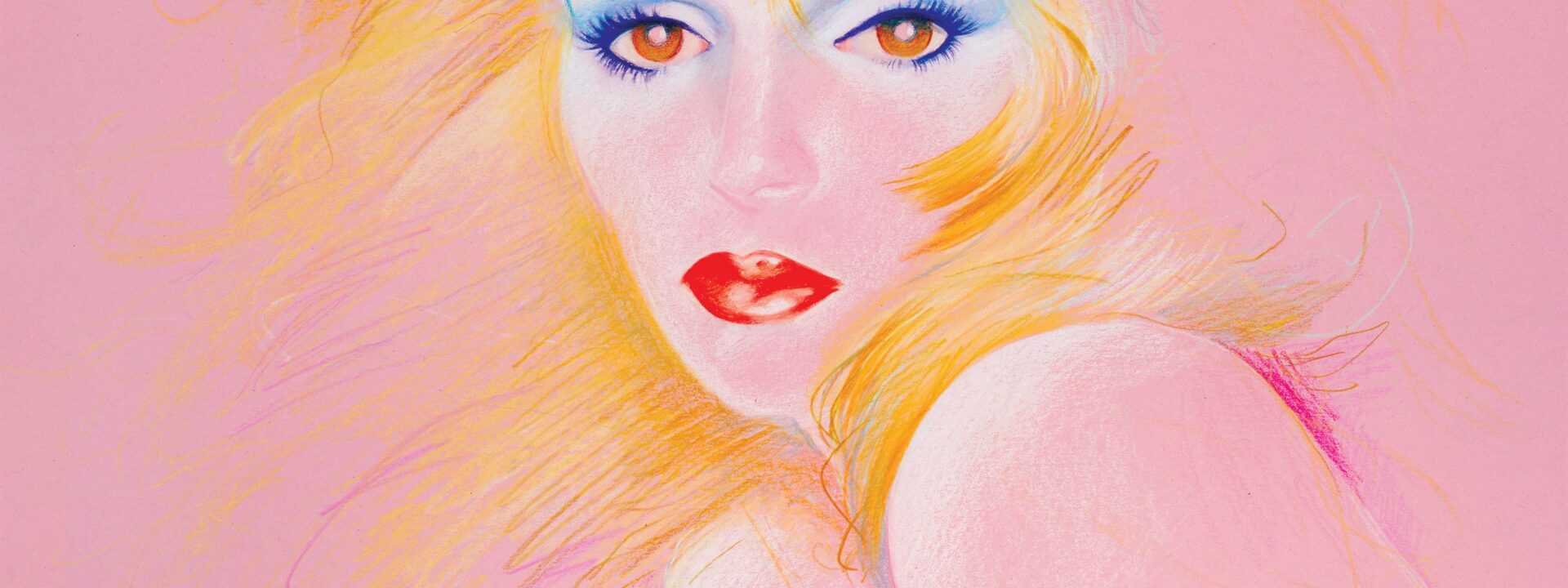

Billy Sullivan’s Candy, 2024 perfectly captures Darling’s radiant beauty—and her lasting legacy.

It’s heartbreaking how familiar this still feels today, isn’t it?

Absolutely. Candy walked a fine line—she was both a glamorous fascination for the elite and an outcast struggling on society’s margins. She moved in those circles but never had money. Beyond her diary and beauty, what drew me to her was that she was a working actress—something I was just beginning to understand in the early 2010s, when Laverne Cox broke through in Orange Is the New Black. Suddenly, things that once seemed impossible felt within reach. Seeing Candy’s face and words echoing across decades—someone who had briefly succeeded in the very thing I wondered if I could do—was deeply inspiring. Most actresses imagine roles they could play, but Candy was the one I truly saw myself in. I never forgot that.

Now you’re working on a film about her. How’s that going?

Let me be clear—we have no funding yet. We’re in the earliest stages of raising money and casting. I spent over a year researching before I could even start writing. Eventually, I had to tell myself: You’ve seen and read enough—now decide what story you want to tell. Which parts resonate most? I stopped trying to make the definitive Candy Darling biography. She’s open to interpretation, as this exhibition shows.

What makes a legend? In Connie Fleming’s Candy Darling Beauty Shot, 2024, the answer is feathers.

She was one-of-a-kind, yet clearly channeled classic blondes like Jean Harlow and Marilyn Monroe—something these artworks highlight.

Marilyn, Kim Novak, Jean Harlow, Joan Bennett… and, oddly, Pat Nixon, according to a New York Times review of Women in Revolt. What stands out here is how these pieces honor Candy as the ultimate blonde—each one a polished, idealized portrait, never candid. Candy had mixed feelings about how the gay men around her loved molding her into their vintage blonde fantasy. Yet she played along, too. That push-and-pull—This isn’t really me versus Here I am, doing it—that was pure Candy.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the imitations…Looking at the ages… I’m struck by how Sunny Suits’ interpretation stands out—how she’s taken a cropped brunette Candy and placed her on the cover of French newspaper Libération. There’s irony and boldness here, a sense of pushing boundaries with Candy’s image and what she represents. This version feels more playful, more mischievous—not the typical blonde bombshell people associate with Candy, but it reflects her earlier days as a street queen in the Village. That was her before she fully embraced the blonde persona, which is what people latched onto back then and still do today.

A pre-blonde Darling, sketched across the cover of Libération, with Sunny Suits’s Study of Candy Darling (After Scavullo), 2024.

What inspired her shift from brunette to blonde? Was it entering Warhol’s world?

She and her friends were part of a collective creative process, much like young artists today. Jackie Curtis, her close friend, played a big role in rebranding her as Candy Darling instead of Hope, her earlier name. People noticed she had a fascination with classic blondes, and through downtown performances, amphetamine-fueled nights, and the larger-than-life expressions of the queer avant-garde, there was this idea of self-mythologizing—Don’t dream it, be it. Create the version of yourself you want to see.

When she fully became that vision, that’s when people really took notice. Warhol and Paul Morrissey saw in her an idealized femininity, executed flawlessly by someone who wasn’t biologically a woman—just as striking as Edie Sedgwick, Brigid Berlin running naked through Max’s Kansas City, or Andrea Feldman’s wild antics. It was a spectacle that stood out in a crowd where everyone was vying for attention from the new tastemakers bridging the avant-garde and the mainstream.

Is that era a focus of your film?

I can’t reveal too much about the script, but my connection to Candy is through her as an actress. I’m interested in her work—both onscreen and onstage. It’s a showbiz story, following her major roles and how she chased her Hollywood dreams, succeeding as much as the times allowed. She was ahead of her era, and that resonates with me. I need to tell her story because it makes me—and so many others—feel less alone.

There’s a responsibility in bringing her to the screen…

Like the artists in this exhibition—Connie Fleming, Kabuki, Tabboo!, Sunny, Jimmy—I’m mindful of how Candy would want to be portrayed. I want to honor her truth without shying away from it. Everyone here clearly loves her, and that question lingers: How would she want to be seen? Even in Elliott Vera’s piece, there’s a warped, dreamlike quality—like how Lou Reed might have seen her at Max’s, high on heroin, before going home to write that song about her.

For Nef, Elliot Vera’s Candy, 2025, evokes Lou Reed and the infamous Max’s Kansas City.

What about the other images?

I love Jimmy Paul’s work—the shade of blonde he used around her face is perfect.Let’s talk about all the different shades of blonde on display—there’s the perfect white-blonde of Connie and Lorena, and Kabuki’s dramatic Erté-inspired look with feathers. But the truth about Candy’s hair was that she couldn’t usually afford professional coloring, so she often had to settle for student stylists. In her diary, she writes about wanting a refined ash blonde, but sometimes all she could get was something brassy and uneven. Jimmy Paul appreciates the glamour of a thrifty, streetwise hairstyle—you can see it in his work for Vogue and beyond. Outside the polished lighting of Francesco Scavullo’s studio, Candy’s blonde wasn’t always flawless—but there’s nothing wrong with that pristine white-blonde either.

In Drake’s photos, her hair is a golden yellow, which reminds me of a diary entry or letter where she describes her childhood. She talks about wrapping yellow towels around her head, draping her mother’s ocelot coat on the floor, and adding blue dye to the bathtub to create a Technicolor effect. The blue eyeshadow, yellow hair, and pink background in Drake’s photos feel like stepping into Candy’s Technicolor fantasy—it’s like he’s taken us from Kansas to Oz.

Tracking Candy’s hair color alone tells a fascinating story about her. You can sense her emotions through these images—while many capture her dreamy, starlet persona, Sunny’s photos stand out because they reveal a weariness and frustration rarely seen elsewhere.

One of the most powerful images of Candy, though not mentioned here, is Peter Hujar’s portrait of her near the end of her life. It captures both her beauty and her vulnerability. By inviting someone to photograph her on her deathbed, she was crafting her final statement—not just as the quintessential Hollywood blonde, but as the quintessential dying Hollywood blonde. That role was one she embraced.

As for the movie, I’ll share one detail: Hujar’s hospital photo is so striking that I realized I couldn’t tell that part of her story better than she did herself. So when it came to her tragic ending, it made sense not to recreate that scene—because she was performing until the very end.

Finally, a simple but inevitable question: to bleach or not to bleach for the role?

I’ve recently started shaping my eyebrows after years of keeping them natural. We lived in the Cara Delevingne era for so long that I was happy with that, but now I’ve been thinning them out to see how far I can go. After Barbie, I dyed my hair red, but now I’m letting it return to its natural color. I’ll work with a talented film hairstylist to figure out what we can achieve with wigs versus real hair. If bleaching is necessary, I’ll do it.

(This conversation has been edited and condensed.)