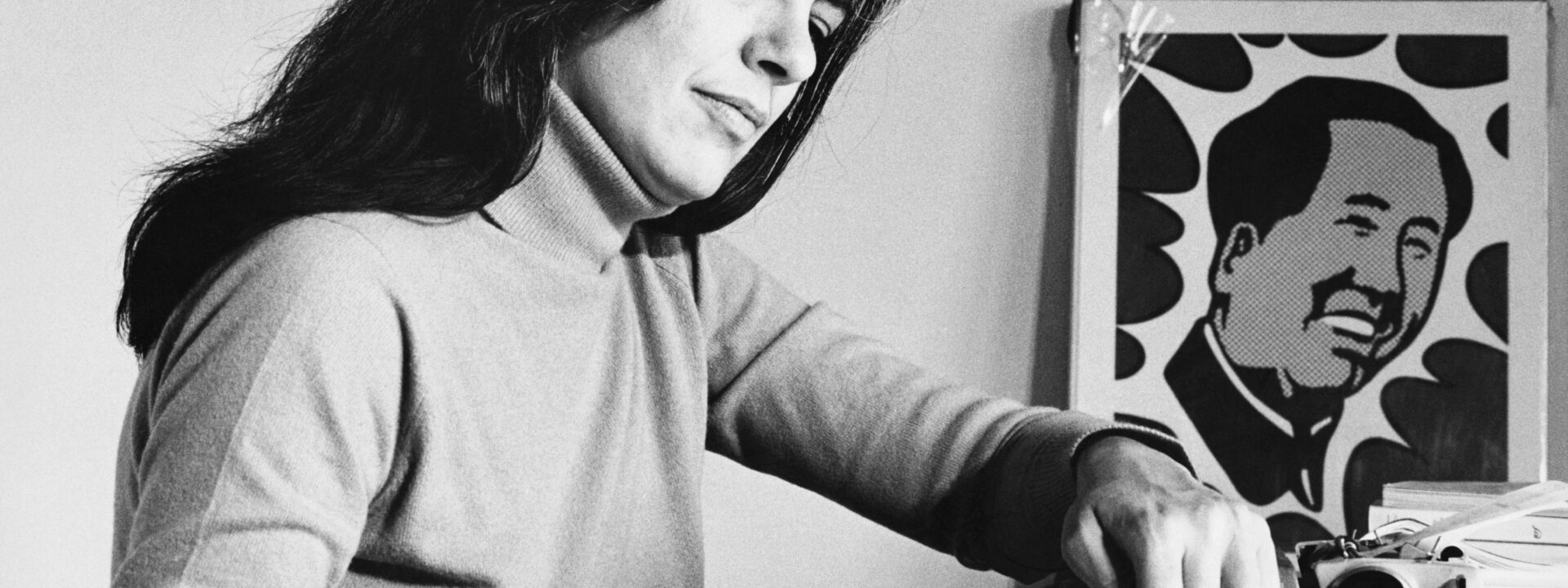

“Susan Sontag Tells How It Feels to Make a Movie,” written by Susan Sontag, first appeared in the July 1974 issue of Vogue. To explore more highlights from Vogue’s archives, subscribe to our Nostalgia newsletter here.

Making a film is both a privilege and a life of privilege. It involves endless attention to detail, anxiety, conflicts, a sense of confinement, fatigue, and moments of joy. At times, you’re overwhelmed by affection for your collaborators, while at other times, you feel misunderstood, disappointed, or even betrayed by them. Filmmaking is about seizing inspiration as it comes, but also about missing opportunities and realizing that you’re the one to blame. It’s a mix of gut feelings, small-minded calculations, strategic leadership, daydreams, stubbornness, elegance, bluffing, and taking chances.

It’s no secret that the risk involved in making a film feels much greater than in writing. When I tell friends I’ve finished a piece of writing, no one asks with concern, “Are you happy with it?” or “Did it turn out as you wanted?” But that’s exactly what I’m asked after finishing a film. This suggests that writing is seen as a straightforward process from idea to execution, where the writer’s intentions are clearly reflected in the final work. If they’re not, the writer might not even notice. However, with film, everyone assumes that the journey from the director’s vision to the finished product is full of unavoidable dangers and compromises, and that every film is a survivor of a tough obstacle course.

They’re not wrong. Writing requires knowing what’s interesting in your mind, having the skill to express it, and the patience to sit at a desk long enough to get it down. It also demands the judgment to recognize when it could be better and the persistence to revise until it’s the best you can do. Writing is a private struggle between you and your inner demons, or between you and your typewriter—a solitary act of will. But willpower alone isn’t enough in filmmaking. Directing a film means not only being insightful about yourself, the world, and language but also dealing with unpredictable elements like actors, equipment, weather, and budget, which often spiral out of control. Things that can go wrong often do. Orson Welles wasn’t far off when he said a director is someone who oversees accidents. For someone like me, used to the solitary discipline of writing, it’s a refreshing change to step out and confront those accidents, trying to manage them. Despite the disappointment when the final film doesn’t match your original idea, you must appreciate what luck has given as well as what it has taken away. It’s a relief to hear voices other than my own and to be challenged by a reality where, at the typewriter, I might have won easy victories through sheer will.

Of course, there’s a big difference between making scripted films with actors—”fiction” films—and diving into reality without a script for a documentary. But it’s not always what you’d expect. After making two fiction films in Sweden (Duet for Cannibals in 1969 and Brother Carl in 1971), I thought my documentary filmed in Israel during the recent Arab-Israeli war with a small crew would be less personal. The result, a feature-length color film I finished editing this spring and premiered in New York in June, surprised me. Though it’s a “documentary,” Promised Lands…”Promised Lands” is the most personal film I’ve created. It’s not personal because I appear in it—I don’t—or because it includes a voice-over narration, which it doesn’t. Instead, it’s personal due to my connection with the material, which I discovered rather than invented, and how perfectly it aligns with themes in my writing and other films. The intricate reality I encountered in Israel while filming last October and November captured my long-standing interests more effectively than the two scripts I had written and filmed in Sweden.

Throughout the entire shoot, the constant threat or presence of war created a quixotic atmosphere where every challenge felt like an adventure. Everything turned into a risk, whether it was the uncertainty of funding from my dedicated French producer or the danger of injury or death, as soldiers warned us about landmines while we filmed in the Sinai Desert.

When I asked a soldier about the mines, he said they were buried just inches under the sand and invisible. We pressed on anyway, walking to get a closer look at the Egyptian Third Army. We got great footage, even a scoop, though it ended up being cut. Carrying our heavy equipment, we felt more foolish than brave, like Dietrich in the final scene of “Morocco,” following Gary Cooper across the desert in high heels.

Filming lasted five grueling weeks, often fifteen hours a day. Each night at the hotel, after crisscrossing the small country in our rented minibus, I’d lie awake making notes on the film taking shape in my mind. My goal was to create a truthful documentary with the same care—or artifice—as a fiction film. In fiction, I could write a script, direct actors, and control every detail. Here, events unfolded first, and the script came later. Reality wasn’t something I invented; I chased after it, often stumbling under the weight of a tripod. Yet, in the end, the film captured the reality I already understood, reflecting the images and rhythms in my head. Tuned into sadness and the sorrow in things, I infused “Promised Lands” with that emotion. Sadly, it’s not just in my mind; it’s what Israel seems to be about at this moment.

I hesitate to call nonfiction films “documentaries” because the term is too limiting. It implies the film is merely a document, but it can be much more. Just as fiction films parallel novels and short stories, nonfiction films can draw from a range of literary models. Journalism is one—film as reportage. More analytical writing is another—film as an essay. For “Promised Lands,” possible parallels include the poem, the essay, and the lamentation.

Fiction films with actors focus on developing a plot, while nonfiction films aim to represent conditions, as Bertolt Brecht described for epic theater. Theater, reliant on actors, struggles to escape “action,” but films, especially nonfiction, can achieve this.

In “Promised Lands,” I aimed to represent a condition rather than an action. Having this purpose doesn’t make the film any less concrete.On the contrary, it must be—especially because part of my focus is war, and any portrayal of war that fails to reveal the horrifying reality of destruction and death is a dangerous lie. This film explores a mental landscape as much as a physical and political one. Old people pray. Couples shop in a market. A Bedouin woman chases her goat in a nomadic camp. Palestinian schoolgirls stroll down a street in the Gaza Strip under the watchful eye of an Israeli patrol. Soldiers lie unburied on the battlefield. Grieving families weep at a mass burial held just after the ceasefire. In a military hospital outside Tel Aviv, a shell-shocked soldier clumsily tries to bandage a cooperative male nurse, reliving the unbearable moments when he dragged his already dead comrade from their burning tank and attempted to give him medical aid. In a hotel room, a melancholy Israeli in his forties reflects on the paradoxes of Jewish historical destiny. Modern buildings rise in the stark, lunar-like desert.

Why these moments and not others? That’s the mystery, the choice, the risk. In a documentary, the director doesn’t invent. Still, choices are always being made—what to film, what to leave out. In the end, you see what you have the eyes (and heart) to see. Reality shouldn’t be approached with servility, but with reverence.

To my friends, I’ve said, “Yes, I’m pleased with the film.” “Yes, it turned out pretty much as I hoped.” That’s not entirely true. It turned out better than I hoped. Luck was on my side; unexpected things happened. I “presided.” Tears flowed—mine, the producer’s, the crew’s. And the camera rolled, the Nagra recorded. The resulting hour and a half of film is faithful to what I experienced there and to things I’ve always known and am still trying to express.

Promised Lands doesn’t tell every truth about the conflicts in the Middle East, the October War, the current mood of Israel, or about war, memory, and survival. But what it does tell is true. It was like that. To tell the truth—even just part of it—is already a marvelous privilege, a responsibility, a gift.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about From the Archives Susan Sontag on the Experience of Filmmaking designed to be clear concise and helpful for a range of readers

General Beginner Questions

1 What is From the Archives Susan Sontag on the Experience of Filmmaking

Its a collection of previously unpublished or hardtofind writings interviews or notes by the celebrated intellectual Susan Sontag focusing specifically on her thoughts challenges and personal reflections about making films

2 I know Susan Sontag as a writer and critic What films did she actually make

She directed four films Duet for Cannibals Brother Carl Promised Lands and Unguided Tour

3 Why would a famous essayist like Sontag want to make films

She saw filmmaking as another powerful form of intellectual and artistic expression a way to explore ideas visually and sensorially that she couldnt fully capture with words alone

4 What are the main themes she discusses about her filmmaking experience

Common themes include the struggle to translate ideas from the page to the screen the collaborative yet often frustrating nature of film production the difference between being a critic and a creator and the unique power of the cinematic image

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 How did her background as a critic influence her approach to directing

Her critical eye made her highly conscious of cinematic form and history However she often wrote about the challenge of moving from analyzing someone elses work to generating and defending her own creative choices on set

6 What was Sontags view on the relationship between the director and the crew

She found the collaborative process both essential and difficult She appreciated the specialized skills of her crew but sometimes struggled with the compromises required when her artistic vision met practical or interpretive resistance

7 Did she write about the difference between European and American filmmaking cultures

Yes she often contrasted the more directordriven artistically ambitious European cinema she admired with the more commercial and industryfocused system in America which she found less hospitable to intellectual filmmaking

8 What specific technical or practical challenges of filmmaking did she highlight

She wrote candidly about the immense pressure of the