Podczas Tygodnia Designu w Mediolanie można liczyć na pewne doświadczenia: podziwianie luksusowych sof, podglądanie zwykle niedostępnych apartamentów i picie zdecydowanie za dużo negroni. Ale coś bardziej zaskakującego? Obserwowanie, jak mieszkańcy w każdym wieku zajmują miejsca na ławkach w pięknej, nastrojowej (i uroczo zakurzonej) zabytkowej bibliotece. A potem słuchanie, jak modelka Cindy Bruna czyta fragment mało znanej japońskiej powieści z 1957 roku – opowiadającej o żonie wysłanej, by znaleźć konkubinę dla swojego męża. Gdy Bruna zamknęła książkę i zwróciła się do stojących obok pisarek, sygnalizując początek dyskusji, w sali zapadła całkowita cisza.

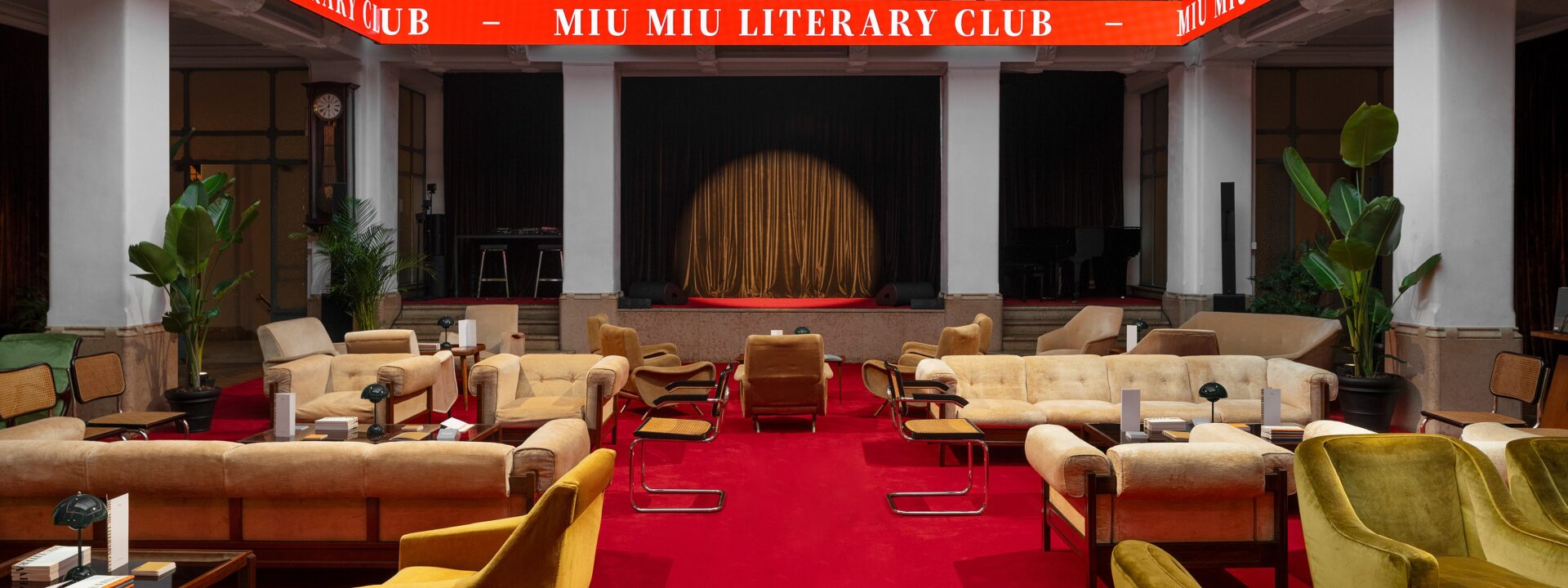

W ten sposób znalazłam się w czwartkowe popołudnie na drugiej edycji Miu Miu Literary Club. Wydarzenie, trwające dwa dni w Circolo Filologico Milanese – centrum kultury języków obcych – rozpoczęło się od dyskusji panelowych w bibliotece, by później rozlać się na żeliwne schody i drewniane hole budynku. W końcu stylowy tłum (z mnóstwem widocznych logotypów Miu Miu) zgromadził się w wielkim atrium, sącząc spritze pod migoczącym wyświetlaczem LED z nazwiskami prelegentów. Następujące po tym występy – muzyka Joy Crookes i Pip Millett, słowo mówione Jess Cole i Kai-Isiah Jamal – wszystkie skupiały się na eksplorowaniu kobiecości przez słowa. (Szczerze mówiąc, termin w środku tygodnia był zbawieniem – po dniach przemieszczania się między showroomami, sama przyjemność było usiąść i przyswoić coś naprawdę prowokującego do myślenia.)

Rozmawiając z Olgą Campofredą, urodzoną we Włoszech pisarką kuratorującą wydarzenie, było jasne, że to efekt ścisłej współpracy z samą Miuccią Pradą. Kilka lat temu Prada skontaktowała się z nią po przeczytaniu artykułu Campofredy o dorastaniu we Włoszech na początku lat 2000. i jej frustracji związanej z męskocentrycznym kanonem literackim wykładanym w szkołach. „Kiedy pani Prada prosi cię o coś, nie mówisz nie” – powiedziała Campofreda z uśmiechem. „To było marzenie”.

Marzenie – tak, ale urzeczywistnione ciężką pracą. Po zeszłorocznej edycji Campofreda spędziła lato, zgłębiając zapomniane klasyki pisarek, by zainspirować tegoroczne dyskusje. Stworzyła długą listę, a następnie spotkała się z Pradą, by dopracować wybór. „Pani Prada cały czas podkreślała znaczenie edukacji, studiowania i krytycznego myślenia” – wyjaśniła Campofreda. „W ten sposób narodził się temat edukacji kobiet”.

Gdy temat był już ustalony, wybrano książki – przy znaczącym wkładzie Prady. „Simone de Beauvoir była jednym z pierwszych wyborów, za którym opowiadała się pani Prada” – zauważyła Campofreda, wskazując na Nierozłącznych – napisanych w 1954, ale opublikowanych dopiero w 2020 – za ich szczerość w opisie przyjaźni kobiet. Druga książka, Lata oczekiwania Fumiko Enchi, była równie odważna w eksploracji życia kobiet. Tekst wyróżniał się brutalnie szczerym podejściem do kobiecej seksualności. „Fumiko wydała mi się szczególnie ważna, ponieważ porusza unikalny aspekt edukacji kobiet – edukację seksualną” – wyjaśniła Campofreda. „Była pionierką wśród pisarek podejmujących temat kobiecego pożądania i jedną z pierwszych, które zajęły się koncepcją męskiego spojrzenia, formalnie zdefiniowaną w akademii dopiero w latach 70. Była naprawdę przed swoim czasem”.

Sama pani Prada podzielała te odczucia. „Poprzez swoje powieści Simone de Beauvoir i Fumiko Enchi kwestionowały stereotypy, które wciąż funkcjonują w naszej kulturze” – powiedziała Vogue’owi przed wydarzeniem. „Osadzając te tematy w centrum dyskusji, chcemy zwiększyć świadomość na temat edukacji kobiet. Jak uczymy młode dziewczyny samostanowienia? Jak przygotowujemy je, by stały się niezależnymi kobietami przyszłości?”

Do dyskusji o powieści de Beauvoir, moderowanej przez pisarkę i kuratorkę Lou Stoppard, Campofreda i Prada zaprosiły trzy autorki, których dzieła podobnie podważają tradycyjne wyobrażenia o kobiecości: włoską pisarkę Veronikę Raimo, pochodzącą z Indii Geetanjali Shree oraz amerykańską autorkę Lauren Elkin, która mieszka w Paryżu i wcześniej przetłumaczyła Nierozłącznych na angielski.

Wszystkie trzy zauważyły, jak aktualna wydaje się dziś ta książka, ale Elkin była szczególnie poruszona. „Wczoraj przeczytałam ją ponownie w samolocie i tym razem uderzyła mnie inaczej” – powiedziała. „Z perspektywy Amerykanki martwię się o moje trzy siostrzenice dorastające w kraju, gdzie prawa kobiet są coraz bardziej zagrożone. Widać powrót sztywnych, tradycyjnych poglądów na kobiecość – to podstępne. Widzieć, jak w moim własnym kraju odgrywa się ta sama religijna i społeczna opresja, która niszczy Zazę [najlepszą przyjaciółkę protagonistki] w powieści, jest głęboko niepokojące”.

Nawet przy wsparciu marki modowej Elkin postrzega inicjatywy takie jak Miu Miu Literary Club jako pozytywną siłę. Cztery lata po przetłumaczeniu książki, która przez dekady pozostawała w cieniu, cieszy się, że zyskuje nową uwagę. „Wspaniale jest widzieć, jak zupełnie nowa publiczność, w innym miejscu i kraju, angażuje się w tę pracę z pasją” – powiedziała. (Jak zauważyła Campofreda, zeszłoroczna edycja klubu nawet ożywiła popularność jednej z wybranych książek – bez wątpienia pomogła jej widoczność w rękach mediolańskiej śmietanki towarzyskiej przez cały tydzień).

Tymczasem dyskusja wokół powieści Enchi – z udziałem Nicoli Dinana (Londyn), Sary Manguso (Los Angeles) i Naoise Dolan (Berlin, przez Dublin) – pokazała, jak każdy z pisarzy widział swoje własne doświadczenia odzwierciedlone w historii protagonistki. To zaskakujące, biorąc pod uwagę, że bohaterka to żona japońskiego urzędnika z XIX wieku, która początkowo odwiedza domy gejsz, by znaleźć kochankę dla męża, a następnie spędza dekady, maskując samotność i gniew obowiązkową lojalnością. (Manguso zażartowała: „Osobiście uwielbiam gniew – wydaje się, że mam go nieskończone zapasy”).

Dla Campofredy dyskusje wydawały się szczególnie aktualne w kontekście włoskich debat na temat edukacji seksualnej, które cofają się w rozwoju. Choć nie wymieniała nikogo z nazwiska, wpływ partii Giorgii Meloni Braci Włoch był wyraźnie wyczuwalny – grupy, która dążyła do usunięcia tematów LGBTQ+ ze szkół, a nawet protestowała przeciwko Netflixowi za wywieszanie plakatów ich serialu Sex Education na włoskich ulicach.

„Ten temat wciąż budzi kontrowersje w debacie publicznej i politycznej” – zauważyła Campofreda. „Wiemy, że wielu chłopców pierwszy kontakt z seksem ma poprzez pornografię, na przykład. Szkoły nie robią wystarczająco dużo, by temu przeciwdziałać lub nauczyć kogokolwiek – chłopców, mężczyzn, wszystkich – czym naprawdę jest seks. Jak dziewczyny i kobiety rozumieją seks? Swoje własne ciała? Przyjemność i pożądanie? Literatura pisana przez kobiety, dla kobiet, pomaga odpowiedzieć na te pytania”.

Prowadzący panel Kai-Isaiah Jamal.

Fot.: T Space

Nicola Dinan, Naoise Dolan i Sarah Manguso.

Fot.: T Space

To, co sprawiło, że Miu Miu Literary Club był tak wciągający, to fakt, że jego intelektualna głębia nie pozbawiła go zabawy. Rozmowy często stawały się humorystyczne, gdy poruszały absurdalne wyzwania, z jakimi mierzą się kobiety – zarówno w fikcji, jak i rzeczywistości.

Zapytana o podobieństwa między jej powieścią Lost on Me a pismami Simone de Beauvoir na temat kobiecego ciała, Raimo przyznała, że pytanie jest trafne, ale zwróciła uwagę, jak często kobiety muszą odpowiadać na takie zapytania. „W przypadku mężczyzn chodzi tylko o duszę, intelekt…” Zawiesiła głos, po czym zażartowała: „Może mężczyźni nie mają ciał. Kto wie?”

W innym miejscu Dolan, omawiając twórczość Fumiko Enchi, utożsamiła się z wychowaniem protagonistki, żartując: „Moja edukacja seksualna sprowadzała się do: Nie rób tego”.

Prowokujące do myślenia, inteligentne, ale nigdy zbyt poważne? To czyste Miu Miu.