Lorenzo Bertelli believes that artificial intelligence and artisanal intelligence are the twin engines driving the future of fashion. This vision is reflected in Prada’s ongoing investment in training the next generation of skilled talent across its companies.

For 25 years, the Prada Academy—an in-house training school at each of the group’s manufacturing sites—has been shaping the expert workforce behind everything from leather goods to ready-to-wear and footwear. Its reach is set to expand further: with the upcoming full acquisition of Versace from Capri Holdings on December 2, the Academy is ready to begin a new chapter, welcoming an even broader pool of young artisans eager to learn their craft.

During a tour of the pristine Scandicci facility—a key production hub for Prada and Miu Miu leather goods near Florence, employing about 375 people, 71% of whom are women—it was clear that luxury manufacturing is far more than an assembly line. “This is industrial craftsmanship,” noted Andrea Guerra, the group’s CEO. He will work alongside Lorenzo Bertelli as Bertelli steps into the role of executive chairman to reshape Versace, a brand poised to benefit from Prada’s industrial expertise.

“Eighty percent of what we do is made by hands, thought, and heart,” Guerra said. “Leather, a living and rather temperamental material, requires an eye sharp enough to catch differences that would escape even a forensic detective. Without that borderline-obsessive care, Prada products simply wouldn’t exist,” he insisted, praising the art of slowness: “In luxury, there’s no room for haste.”

If craftsmanship moves slowly, the prices of luxury goods certainly haven’t. Guerra was unfazed. “They reflect the intrinsic value of our products, the way they’re crafted,” he argued, making the case that excellence has its own economics. “And so far, our consumers have understood that and rewarded us.” The numbers seem to agree. The Group reported net revenues of €4.07 billion for the nine months ending September 30, 2025, marking a solid 9% year-on-year increase and extending Prada’s streak to 19 consecutive quarters of growth. Retail continued to prove its strength, with sales reaching €3.65 billion, also up 9% year-on-year, supported by strong like-for-like performance and healthy full-price sales. The third quarter grew 8%, in line with the second quarter, despite facing an exceptionally strong 18% growth comparison from the same period last year.

At the Prada Group Academy, the company’s School of Craft, 29 courses were launched from 2021 to 2024, training 571 students—a small brigade of excellence. This year, seven new programs began with 152 enrollments, a healthy 28% increase compared to 2024. Is craftsmanship the new luxury flex?

Those who enter the Academy embark on a journey of continuous learning, a permanent gym for both hands and mind. Yet some trades remain underappreciated. “There are beautiful crafts that simply aren’t perceived as such,” Lorenzo Bertelli noted. The long-cultivated myth of the glamorous office job—shiny badge, ergonomic chair, the whole package—is now colliding with a less glossy truth: many white-collar roles are alarmingly easy to automate.

After a session where Academy apprentices discussed the perks and challenges of training to become the next generation of craftsmen, Bertelli and Guerra sat down to talk about the future of craftsmanship, the company’s evolving industrial model, and the opportunities ahead. Below is an edited excerpt of their conversation.Vogue: Lorenzo, let’s talk about the appeal of manual work. Young people don’t seem to consider manufacturing careers anymore. Everyone wants to study at Bocconi and then go into consulting, but the reality often turns out quite differently. How do we make craftsmanship attractive again?

Lorenzo Bertelli: I think it has a lot to do with how blue-collar and white-collar jobs are marketed. When people imagine office work, they picture a Wolf of Wall Street fantasy. In reality, most end up drowning in spreadsheets and PowerPoints. And as technology advances, it’s increasingly replacing tasks that were once the core of office work. But technology can’t replace an artisan’s ability to work with their hands. We see this not only here in Scandicci but across the company.

Take Luna Rossa, for example: it needs welders, electricians, highly specialized technicians. This technological shift is revealing that many jobs once considered “high value,” like office roles or consulting, are surprisingly easy to automate. Meanwhile, manual trades are gaining even more value. The problem is simply that no one is telling this story well. These are the jobs that will endure.

Today, there’s a shortage of skilled workers in countless sectors. Anyone who’s tried to renovate a house, like myself, knows the struggle: good carpenters, plumbers, builders—they’ve all become unicorns. Knowing how to work with your hands is a priceless skill, and we need to elevate it properly. After all, Made in Italy is built above all on manufacturing. We must make this world as attractive as possible by valuing it and creating the right conditions for it to thrive. It’s still early days, but I’m convinced that in the next 10 to 20 years, the paradigm between white-collar and blue-collar work will be completely flipped on its head.

Vogue: Can you clarify what you mean by “paradigm shift”?

Bertelli: I remember years ago, every other parent was sending their kids to learn coding because coding was “the future.” And now we’ve discovered that AI can code—so maybe you didn’t need all those coding classes after all. In today’s world, the real superpower is being agile and flexible. But there is one area I believe is both stable and built to last—and Italian history proves it: manufacturing.

Sure, iron rods today are made by CNC machines, whereas 50 years ago they were hammered out by a worker on an assembly line, in conditions that were, let’s say, less than thrilling. Since AI is going to eliminate a lot of low-value-added tasks—meaning repetitive, monotonous, mind-numbing work—it will actually create more opportunities to elevate the professions where skilled hands make all the difference. That could be a chef, a pastry maker, an electrician, or someone in manufacturing. So that’s what I mean by a paradigm shift: I see a world where, thanks to AI taking over the boring stuff, we can finally recognize the true worth of people who work with their hands. They’ve always been there; we just weren’t appreciating them properly.

Vogue: How are you approaching technological evolution and the integration of AI into production processes?

Bertelli: I’m not worried, because the manual expertise of our Academy students, as I mentioned, will be our most precious asset. Let me share an anecdote: as you know, we’re working on the space suit for the upcoming Artemis III mission in collaboration with Axiom Space. When we went to Houston, Texas, we had all these images in mind—NASA, space suits, unimaginable capabilities. And yet, the one thing they genuinely needed our help with was… sewing. They didn’t know how to stitch the suit.It’s about patterns—which ones to use and where to place them. Our contribution proved essential. I believe technology will increasingly enable enormous efficiency gains and eliminate even more low-value tasks from daily work. Of course, there will be a transition period: some jobs will inevitably disappear, and in the short term, this shift will cause friction and disruption. But in the long term, I’m convinced it will elevate human work further, especially in manufacturing. I also believe the public and social sectors must do everything possible to ease this transition and make it as painless as possible.

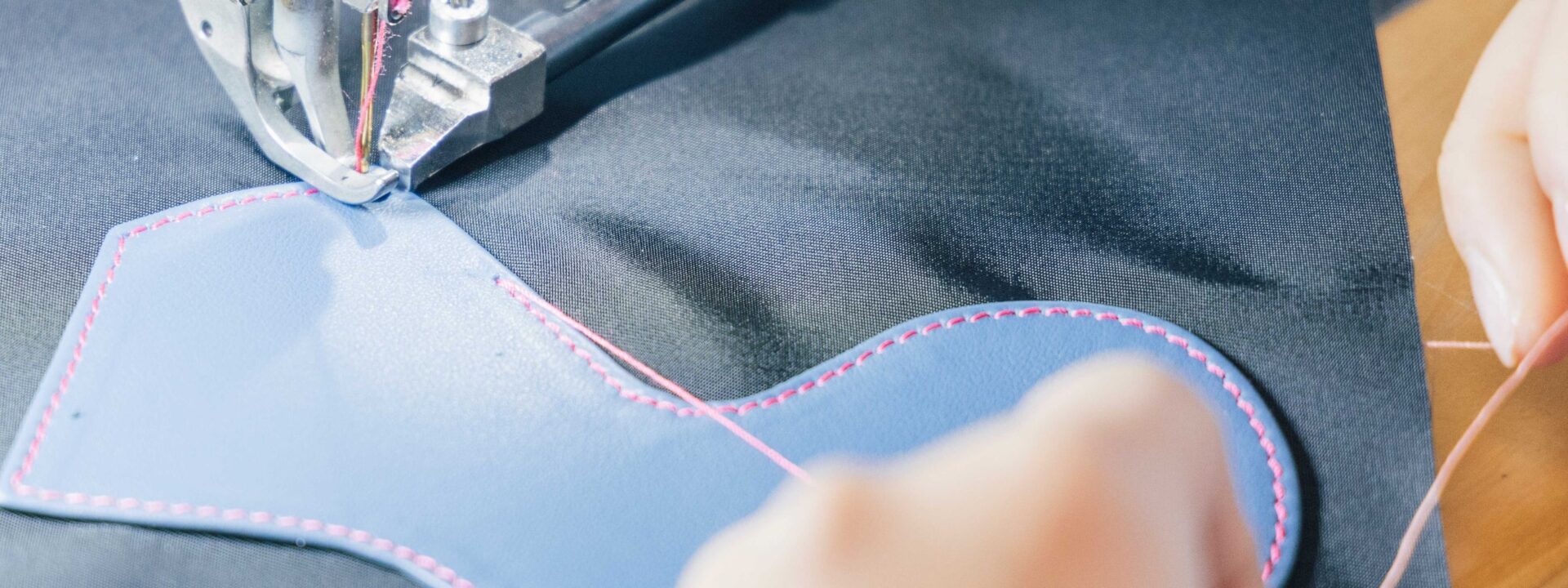

Leather trimmings.

Photo: Courtesy of Prada Group

Vogue: The Made in Italy production process has recently faced scrutiny due to allegations of malpractice within the supply chain. How has your group approached this challenge, and what measures have you implemented over the years to minimize risks that other fashion companies are now encountering with their third-party suppliers?

Bertelli: Unlike much of the industry, in our group, the runway has always gone hand-in-hand with the factory. From the beginning, our approach has been that design and production are inseparable. When you speak with managers from other companies, factories can seem like a distant, abstract world that isn’t their responsibility. That disconnect has contributed to many of the issues making headlines today. For us, it’s a matter of culture and heritage. From day one, my father believed in owning factories. My parents’ story embodies this approach: my mother, Miuccia, dedicated herself to design, while my father, Patrizio, focused on the factories.

This philosophy runs through our entire organization; it’s embedded in our culture. In our Milan offices, business is never discussed without considering the factories, production processes, and their broader impact. Many companies simply don’t take this hands-on approach. Over the years, we’ve already confronted many of the challenges now causing problems elsewhere—not because we were inherently smarter, but because we tackled them early. At the time, some questioned why we would take on such a labor-intensive, costly path when it would have been easier to outsource production and focus on higher margins. It’s an ongoing commitment. Regular inspections, supplier audits, and direct engagement with our factories are constant necessities. But in our experience, there’s no shortcut: understanding your production and being hands-on at every level is the only way to safeguard quality, ensure ethical practices, and maintain the integrity of the Made in Italy label. That’s been our approach from the very start.

Vogue: What does it take to safeguard ‘Made in Italy’ and let its story of excellence resonate authentically?

Andrea Guerra: We will remain incredibly strong when it comes to Made in Italy. Italy’s problem isn’t the “Made in” label, nor our manufacturing, nor our ability to innovate. The real issue is selling our strengths—being able to tell a story, do marketing, engage consumers, and run stores worldwide. Italian companies have always been extraordinary at making things but, unfortunately, not equally extraordinary at selling them.

Lorenzo Bertelli with Prada Academy students at the Scandicci facility.

Photo: Courtesy of Prada Group

Companies like Prada, which decided over 30 years ago to step directly into the world of end consumers, are the exception rather than the rule in Italy. I always use this example: if I ask a French or British entrepreneur, “Tell me about your business,” they’ll take me to one of their stores, restaurants, or hotels. If I ask an Italian entrepreneur the same question, they’ll take me to their warehouse. That’s the difference. In Italy, the tradition of running shops, restaurants, and hotels has always been rooted in family businesses, but we haven’t really taught…We have not taught the next generations—at least not enough, or perhaps only recently—how to evolve in managing consumers. Today, Italy likely produces around 80% of the world’s luxury goods, yet Italian companies account for less than 20% of the sector’s revenue. That is where we lost ground, and where we must improve, by treating this sector as a central pillar of Italian industry.

Vogue: Lorenzo, you’re celebrating 25 years of the Academy today, and next Tuesday Versace officially joins your group. Will there be a Versace Academy?

Bertelli: Versace will now have the opportunity to fully enter our world of industrial production. This means accessing a more structured and sophisticated manufacturing ecosystem, and benefiting from processes, expertise, and capabilities that can elevate the brand’s craftsmanship and operational strength. Here in Scandicci, we’re already preparing to welcome Versace. The Academy will remain a group initiative—after all, whether we make a bag for one brand or another, it’s the same craft. The philosophy stays the same, and we’re continuing on this path.

We’ve never paused our investments. For example, in Milan we’re expanding our high-end leather work, creating an even more sophisticated workshop. Another major investment is a brand-new handbag facility in Tuscany, near Piancastagnaio. We’re building it from the ground up to be fully cutting-edge in sustainability. This facility will also bring together many of our local workers. Beyond that, we have several other projects underway in the Marche region for footwear and knitwear production. From 2019 through the end of 2024, we invested over €200 million to strengthen our industrial infrastructure—and in 2025 alone, we’ve invested another €60 million.

Vogue: How do you plan to integrate Versace into the Prada group without dimming its famously bold identity?

Bertelli: First, we need to get to know the people and the team, and understand what evolution may be needed. I see the first phase for Versace as purely a learning phase. Only after that will we form opinions, gather perspectives, and decide how to move forward. But the absolute priority is meeting the people who make Versace run. Nothing more glamorous than that—for now. Acquiring Versace is an important step, but a calculated one. It doesn’t expose us to major disruption, and it’s a risk we can easily afford. That means we have the luxury of patience: taking things slowly, carefully, and being willing to try, try again, and then try once more.

Vogue: There are many fashion brands that could use both a creative jolt and a financial reboot. The list is long. So why choose Versace, putting €1.25 billion on the table?

Bertelli: Gianni was the man who made a traditionally bourgeois, ultra-elite sector suddenly pop. He brought aspiration into a world where it didn’t even exist. In my view, it was a revolution comparable—dare I say—to what Michael Jackson did in music: he took something aspirational and made it wildly popular, glamorous, and culturally magnetic. Versace still has that fascination today. And importantly, it’s completely complementary to the other brands in our group—there’s no overlap in identity, no risk of one stepping on the other’s toes. It’s a universe of its own. That’s why it stood out among so many options.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Lorenzo Bertelli and Andrea Guerra discussing Pradas manufacturing heritage and the integration of Versace into the group

Beginner General Questions

1 Who are Lorenzo Bertelli and Andrea Guerra

Lorenzo Bertelli is the son of Pradas founders and the Head of Marketing and CSR for the Prada Group Andrea Guerra is the Groups CEO appointed to bring strategic leadership and oversee operations

2 What is Pradas manufacturing heritage

It refers to Pradas longstanding commitment to highquality inhouse production in Italy Its about their expertise in craftsmanship material innovation and controlling the entire manufacturing process to ensure exceptional quality

3 Did Prada buy Versace

No Prada did not buy Versace In 2021 Prada along with its longtime partner Patrizio Bertelli joined a consortium that acquired a controlling stake in Gianni Versace Srl the company that produces the Versace Jeans Couture and Versace Collection lines The main Versace brand remains under the control of the Versace family and Capri Holdings

4 So is Versace now part of the Prada Group

Not directly The Versace lines they invested in are separate but under a shared ownership structure You can think of it as Pradas leadership having a significant stake and influence in expanding those specific Versace product lines

Advanced Strategic Questions

5 Why is Pradas manufacturing heritage so important to them now

In a world of fast fashion and outsourcing its a key competitive advantage It guarantees quality allows for unique innovations protects their intellectual property and supports the Made in Italy brand which is crucial for luxury consumers

6 What benefits does Prada see in integrating the Versace lines they invested in

The main benefits are growth and diversification It allows the group to tap into a different often younger customer segment with Versaces bold glamorous aesthetic complementing Pradas more intellectual and minimalist style It also creates potential operational synergies in areas like production and distribution

7 What are the biggest challenges in managing such different brands under related ownership

The key challenge is