Last fall, after decades of terrible vision that left me unable to recognize close friends across a small room without glasses, I spent $10,000 on ICL surgery—a newer alternative to LASIK where permanent contact lenses are placed inside the eyes. Aside from the slightly intimidating month-long regimen of prescription eye drops afterward, recovery was quick. I haven’t had any serious medical issues, just subtle psychological ones: improving my vision unexpectedly changed how I saw myself.

For the first time in as long as I could remember, I looked in the mirror and saw only my face—no frames hiding my brows, no lenses distorting my eyes. And most noticeably, my nose: bare, no longer split horizontally by black acetate frames.

On a good day, in a good mood, my nose is “striking” or “distinguished.” It has “character,” as my mother puts it. On a bad day, it just looks crooked. “I’m so glad she never fixed it,” a famous artist recently told a mutual friend after meeting me. Though meant as a compliment, I took it as an insult.

Should I have fixed it? A basketball to the face in middle school left a hairline fracture and a slight asymmetry I’d always noticed but never cared about. Now, though, that asymmetry stood out—sometimes literally, catching the light in photos. My friends and family insisted I was overthinking it, but their reassurances didn’t help. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe them—I just didn’t care what they thought! I wanted a professional opinion.

One rainy spring morning, I visited the Park Avenue office of Dr. Lara Devgan, a plastic surgeon with nearly a million Instagram followers and celebrity clients like Kim Kardashian and Jennifer Aniston. Known for “facial optimization,” she specializes in subtle tweaks—like tailoring an old dress rather than ordering a brand-new one.

“You have a ‘deep radix,'” she said, tracing the dip at the top of my nose with her finger. There was also a “widening of the dorsal nasal aesthetic lines”—in simpler terms, the bridge. Some crookedness, likely from past trauma. And finally, she noted, “a little bit of a bulbous and slightly droopy nasal tip.”

At last, some honesty, I thought.

A traditional rhinoplasty could make my nose smaller and straighter. But it would cost around $20,000, require general anesthesia, take up to a year for final results, and turn me into someone who got a purely elective nose job at 37—decades past what I considered the “useful” age for such things.

There were other options. “Modern plastic surgery is all about customization,” Devgan said. Hyaluronic acid injections—acting like a cartilage graft—could soften the bump at the top of my nose and “optimize” my appearance. “We don’t have to make you look textbook-perfect to be happy,” she added.

She was describing a nonsurgical nose job, or “liquid rhinoplasty,” a growing trend that isn’t actually new. (Injecting fillers into noses dates back to the early 1900s, when risky substances like oils and waxes were used.) The first hyaluronic acid filler—also used in skincare for hydration—was FDA-approved for cosmetic use in 2003. Since then, its effects can be seen everywhere, from influencers’ sculpted cheekbones to…Like many people in big cities by 2025, I’d become uneasy about the unnatural look of facial fillers. Whether riding the subway or at a Pilates class, I’d often find myself surrounded by faces that looked slightly puffy, oddly smooth, and hard to place age-wise—almost as if they’d be tender to the touch. But I hadn’t yet noticed—or at least hadn’t recognized—any noses that appeared altered by filler.

For most of the 20th century, nose jobs were seen as a way to fit in, especially among immigrant communities. These procedures often involved removing a lot of cartilage, leaving noses small, sharp, and upturned. But Dr. Raj Kanodia, a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon, told me that patient preferences have shifted in recent years. “People now want to enhance—not change—their features,” he said. Kanodia, who approaches filler cautiously and specializes in subtle rhinoplasties (like the ones he’s done for Khloé Kardashian and Ashlee Simpson), explained that his goal is to highlight patients’ cultural identities rather than erase them. His philosophy? “Fool the mother’s eye.” Surprisingly, he credits social media for this change, as it exposes people to a wider range of beauty ideals. “People want to look like the best version of themselves, not like someone else,” he said.

That’s exactly what I wanted. Sitting in Dr. Devgan’s office, she assured me that choosing a subtle approach wouldn’t close any doors. She compared the procedure to Botox—numbing cream, a few quick pricks, maybe slight redness—but with instant results lasting up to a year. She called it “magical, three-dimensional makeup,” like real-life Facetune. Magic was what I was after: to look better while still looking like myself. Or maybe I was just indulging in wishful thinking. Isn’t that what we all want? To change our lives without actually changing anything?

A few days later, I visited Dr. Michael Bassiri-Tehrani, whose “tip stitch” technique had recently gone viral on TikTok. This procedure—a few internal stitches to lift the nose tip slightly—is usually part of a full rhinoplasty, but he now offers it separately. It’s popular among men who might shy away from a full nose job, as well as women preparing for events where they’ll be photographed smiling (which can make the nose appear longer). Could lifting my nose tip disguise what I’d privately dubbed my “basketball bump”?

Maybe, he said—but he wouldn’t recommend it. If it were up to him, he’d prefer a full, balanced rhinoplasty, which he claimed would ironically look more natural than a series of small tweaks. He took photos of my face, then edited them in Photoshop—raising the bridge, smoothing the bump, adding a bit of volume. When he showed me the results, I was stunned. From the front, I looked almost unchanged, but from the side, my nose was still prominent yet perfectly straight—something filler could never achieve.

I started to fidget, my voice edging toward a whine. I told him I was nearly 40, married, with a baby and plenty of friends. How could I possibly justify major facial surgery?Plastic Surgery?

My hesitation wasn’t entirely rational—I worked out, dyed my hair, and wore expensive, flattering clothes. “Everyone draws the line somewhere,” he said.

High on a kitchen shelf, tucked between neglected DVDs (we don’t even own a player) and coffee table books (now inaccessible thanks to a toddler), sits a plaster bust of Hermes, a reproduction of a 340 BC sculpture. For years, it watched me cook dinner, and only recently did I think to take it down. To my surprise, my grease-smeared god’s nose looked just like mine—perfectly straight, whether by divine power or the sculptor’s hand. I’d never thought to seek beauty inspiration from a deity before, but there it was, in my own kitchen all along.

Dr. Melissa Doft’s office is behind one of those discreet Park Avenue doors, the kind usually entered by women in sunglasses. A friend had described her as gentle, impeccably tasteful, and—most importantly—with a face that looked untouched. “It’s like shopping for makeup at Bergdorf’s,” Doft said. “If you don’t have a brand in mind, you look for the woman behind the counter whose makeup you’d want for yourself.”

Examining my face, she agreed with my previous doctor that a full rhinoplasty would be the best option. There was, as she tactfully put it, “enough mass to work with.” When I brought up my age again, she stopped me.

“The age range for nose jobs is much broader than people think,” she said. She often performs rhinoplasties on women in their twenties, only for their middle-aged mothers to follow suit. For that reason, she avoids results that are “too cute”—a nose should look good not just on a teenager but on an older woman too.

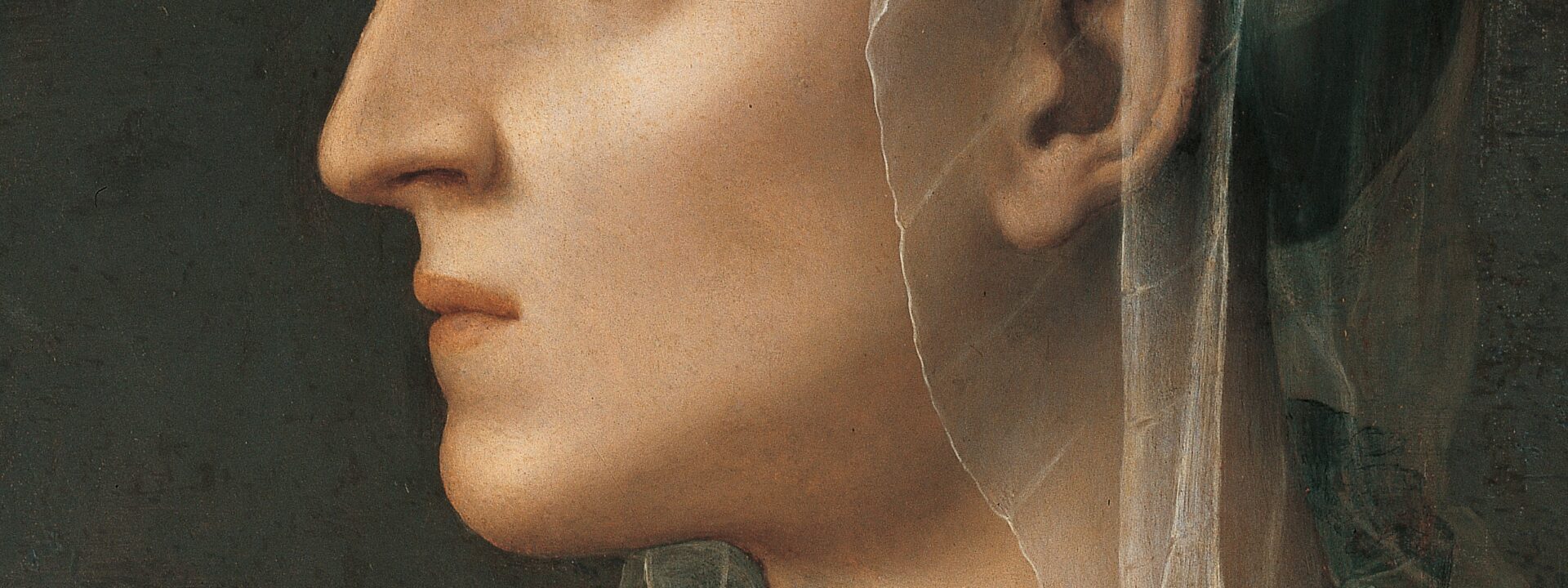

“When considering noses,” she explained, “you want to look at what’s been idealized across history. Symmetry, straightness, a slight flare at the bottom—like the open wings of a bird.”

It sounded beautiful—and not far from my own nose. “But it’s like getting into a pool,” Doft said. “Some dive right in, others ease in step by step, and some never go in at all.”

I was lingering at the shallow end, toe testing the water. Then she offered me a lifeline.

“We could try a bit of filler,” she said. “Right now, if you want.” The immediacy surprised me—she must have sensed my hesitation. “It’s dissolvable if you don’t like it.”

She left to retrieve a syringe of RHA, a newer filler introduced in 2020 that she found more natural-looking than older options. Cradling my chin, she injected the top of my nose twice, massaged it, then added a drop to the side to balance the asymmetry. After a final rub, she handed me a mirror. My nose wasn’t smaller, but it was smoother—less like a topographical map, more like a child’s drawing of a mountain.

“No one will notice but you,” she said.

“So, did you get a nose job?” my husband asked when I got home.

“No,” I told him. “I didn’t do anything.”

My quest was over—and with it, the urge to keep looking in the mirror.I avoided mirrors—not because I feared what I’d see, but because I was tired of obsessing over my face. Every doctor I consulted defined the perfect nose as one that blends seamlessly into the rest of the face. But I learned that the real perfection lies in a nose so natural, you stop thinking about it altogether.