At 15, I cherished escaping Florida’s sticky heat for the cool darkness of my night photography class. There, I’d watch images from my father’s hippie days slowly come into focus under the red light, revealing glimpses of a life I never knew.

For years, Dad worked long hours while I grew into a teenager. I moved in with him at 14, right after he and Mom split. When I discovered three undeveloped film rolls in his closet, I signed up for a photography class through my high school. Every Wednesday, Dad drove me there and back. One night after class, he spotted an Applebee’s sign advertising two-for-one steaks with sides.

As we sat in the booth, I spread the photos between us. One showed a woman in a crocheted bra top staring boldly at the camera, biting her lip. Others captured strangers chatting, playing guitars, or blowing smoke rings, nearly all in bell-bottoms.

“You remember how I used to say, ‘Before you were born, I was a pirate’?” Dad asked. When I nodded, he tapped the photos. “It started around this time.”

Over our cheap steaks and limp vegetables, he shared how his criminal life began in the late 1960s – first unloading marijuana barrels in New Orleans, then captaining ships, eventually flying cocaine from South America. “I made those mistakes so you wouldn’t have to,” he said. “Drugs are dangerous – and why I’ll never meet my grandkids.” I blinked, half-doubting his wild stories, unaware the hepatitis C he’d caught during those years would take his life months later.

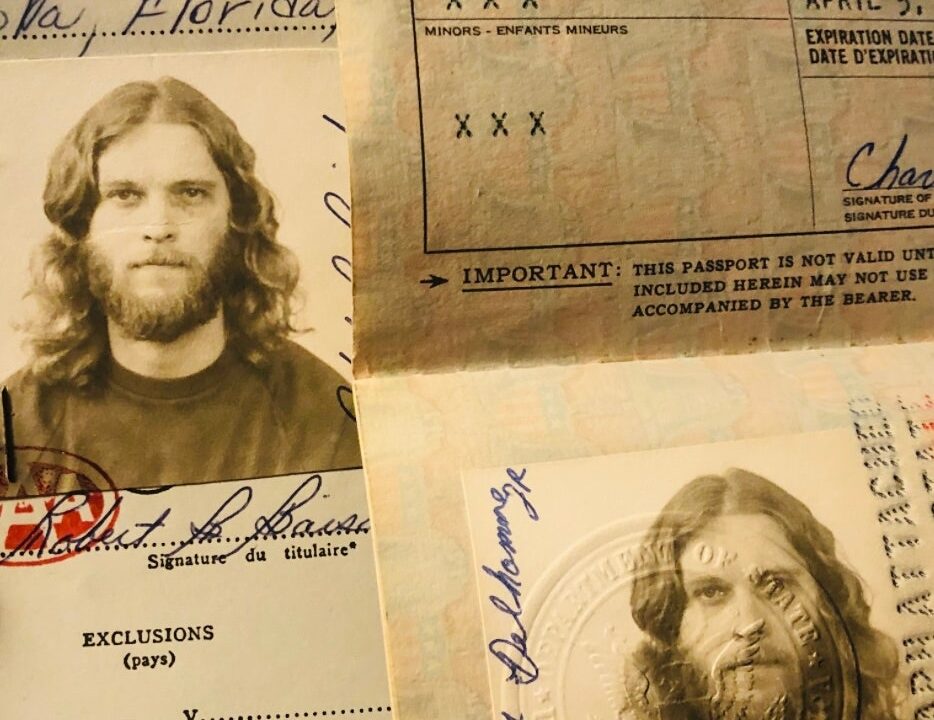

After his death, I found fake IDs, birth certificates, and his old pilot’s license. Sitting on his bedroom floor as sunset painted everything pink, I pieced together how a poor Gulf Coast kid wound up in South American jungles, grinning beside smugglers with a machete like other dads pose with fishing catches.

Crime gave my father adventure and control after a poor childhood. By my teens, he overflowed with warnings and determination to give his kids better lives. “What doesn’t kill you can leave you broken,” he’d say, rejecting the idea that hardship builds strength. “If you dance, you pay the fiddler. Choose your dance carefully.”

To Dad, resilience wasn’t earned – it was chosen. Over Applebee’s dinners, he explained quitting smuggling when I was born, becoming a park ranger to protect nature he loved, then selling fire alarms to “save lives instead of ruin them.” In his final days, he made me promise to work hard, follow rules, and outlive him.

For twenty years, I heeded his advice – avoiding the drugs and violence that claimed relatives’ lives. I became a speech pathologist, had kids young, often worked multiple jobs. Still, I lost loved ones, buried a stillborn baby, raised three wonderful disabled children, and divorced. When friends called me “resilient,” I didn’t feel strong – just exhausted. While experts define resilience as continual adaptation, all that… [text cuts off]Changing and adapting came at a price. Then, just before the 22nd anniversary of my father’s death, I discovered an old journal where I’d taken notes for the memoir he’d wanted to write. One page said: “I used to go crazy for fireworks. Now I fall in love with fireflies. The amount of light doesn’t matter—they both shine the same way.”

My dad thought he’d transformed his life through hard work at his steady job, but those words made me realize his most meaningful work happened inside. Instead of chasing grand, dramatic thrills, he learned to appreciate simpler joys—a great comic strip in the Sunday paper, a perfectly crispy fried bologna sandwich, or the feeling of cool water and warm sand underfoot at our hometown beach. For him, resilience wasn’t just endurance—it was a daily habit of wonder, like keeping a gratitude journal. It meant noticing the small, bright moments and letting himself be captivated by them.

Reading his notes, I made a promise—to my dad, to myself, to my kids, and to everyone I love: I’d allow myself to feel awe, even in the dullest or hardest times. It’s not about forcing optimism or pretending pain doesn’t exist. It’s about making room for both the hurt and the chance that something beautiful might be there too—like a lone firefly flickering in the dark, however briefly.