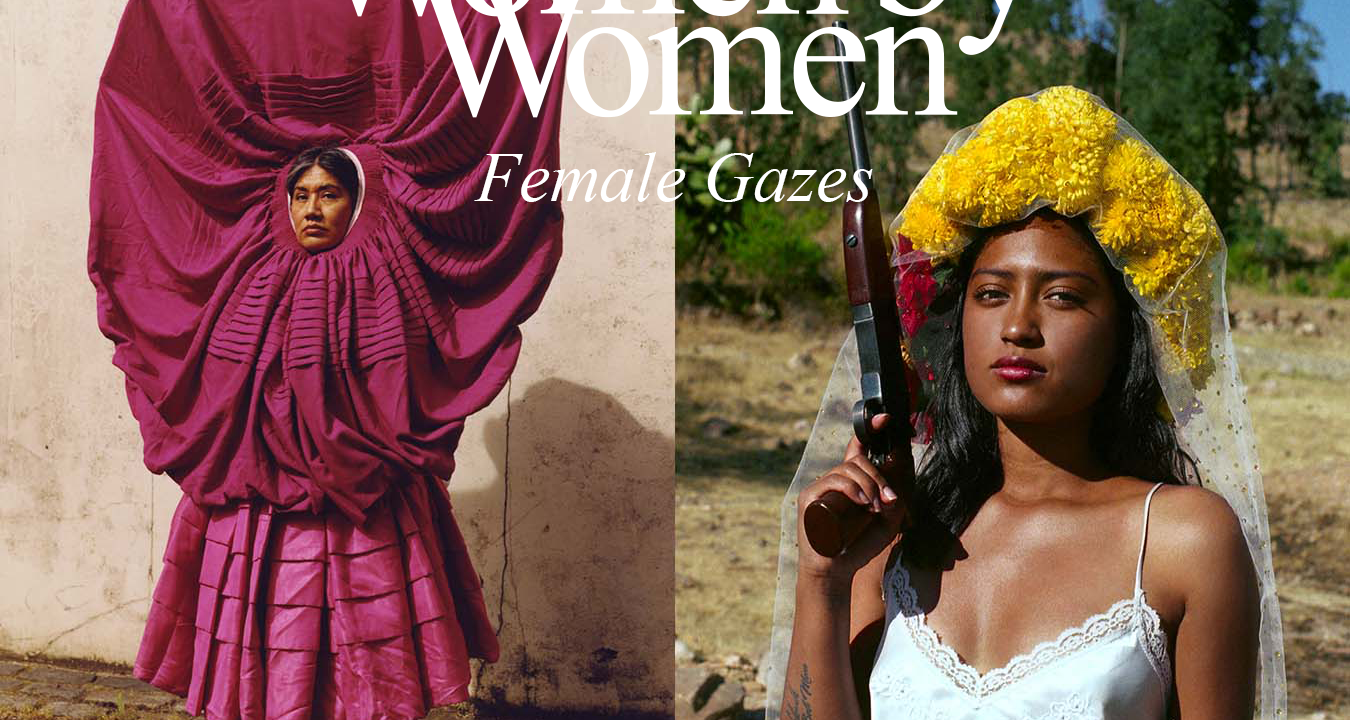

Last year, we launched PhotoVogue Female Gaze, a series of interviews exploring themes from the first PhotoVogue Festival in 2016, featuring photographers from our community. This year, with our global open call Women by Women, we wanted to create a more interactive space where women artists could exchange ideas, discussing both the commonalities and differences in their work and perspectives. That’s why we renamed the series Female Gazes.

For our first conversation, we invited artists Ana Margarita Flores and Marisol Mendez to discuss their projects Where These Flowers Bloom and Madre. Both Ana and Marisol are from Latin America but left the region at different stages of their lives. We talked about identity, belonging, and embracing the many cultures within them—acknowledging contradictions while dismantling old beliefs. We also touched on being women in the industry, the responsibility of portraying others, and navigating a creative career where financial savvy is just as important as artistic vision. The result was a rich discussion weaving together contemporary themes like colonization and gender structures, explored with both sensitivity and humor.

### Where These Flowers Bloom

Ana Margarita Flores

CATERINA DE BIASIO: Thank you both for joining me. To start, I’d love to hear how your projects began and the meaning behind their titles.

MARISOL MENDEZ: I started Madre in 2019 after returning to Bolivia from studying abroad—first in Buenos Aires, then in London, where I did a master’s in fashion photography. At the time, fashion was undergoing a shift, with people questioning dominant narratives. Yalitza Aparicio, an indigenous woman and star of Roma, even appeared on a magazine cover. I expected to find a more diverse cultural landscape back home, but instead, I saw the same outdated portrayals of women in media. As a visual artist, I wondered: Why aren’t we showcasing the beauty around us? So Madre became my way of challenging these narrow depictions by photographing the women I encountered daily.

(Image: Killa by Marisol Mendez)

Around that time, my mom found our family album while cleaning, which was eye-opening. It revealed the diversity within my own family, even though women of the past had fewer opportunities to express themselves. The album also made me reflect on Bolivia’s classist and racist history, pushing me to critique my family’s past while imagining a new future.

The project is called Madre—a word that embodies both the incredible power of women to create life and the historical confinement of women to reproductive roles. For me, Madre celebrates womanhood while protesting the limited spaces we’re still expected to occupy.

(Image: Dual by Marisol Mendez)

CDB: I wanted to bring you two together because of your many parallels, but especially because you both left home at different points in your lives.ANA MARGARITA FLORES

I really relate to what Marisol said about returning to Bolivia and reconnecting with aspects of her culture through her family.

For me, going back to Peru became meaningful after I switched careers and started studying fashion photography. Photography gave me a way to ask questions I hadn’t considered before. My degree pushed me to explore the message behind my work, beginning with self-reflection. That process led me to research my own roots.

I returned to Peru, spending time with my grandmother and digging through family archives. In Cusco, I met indigenous communities collaborating with a high-end restaurant and research center called Mil. They shared their deep knowledge of the land, passed down since pre-Incan times.

View of Peru from the plane.

Ana Margarita Flores

Even though I knew about this history, I’d never connected with these communities directly. It was a wake-up call—I realized how little I truly knew about my own country. Growing up, Peruvian culture was present in my home through food and language, but we rarely discussed its history. Honestly, I never questioned it much while living in Switzerland with my parents. It wasn’t until my photography studies that I began deconstructing these layers.

During my 2023 trip, I researched colonialism and met people who’ve faced centuries of discrimination. I felt proud to engage with them and learn from their preserved knowledge, but also angry at how marginalized they remain—judged for their lack of formal education, skin color, or language.

For my final project, I explored textiles as both a language and an act of resilience. My research deepened into something deeply personal. I had to confront my own identity—being Peruvian with parents from Peru, yet perceived as white there, while in Europe, I’m seen as brown. My grandmother, who’s brown-skinned, endured discrimination, yet I, her grandchild, am treated differently.

I drew parallels between indigenous women’s history and my grandmother’s life. Choosing Cusco was intentional—I was born there, and returning felt like reclaiming my roots. I took self-portraits at my family’s old house, an emotional experience.

Naming my project came unexpectedly. While biking and listening to Tyler, the Creator’s Where This Flower Blooms, it clicked. I adjusted it to Where These Flowers Bloom—a nod to three women’s stories.

This is why Marisol’s work resonates with me. We both navigate identity through family history.My mother, my grandmother, and I all share Peru as our common ground. Returning there helped me blossom—not just as an artist, but as a person.

Ana’s mother, Ana Margarita Flores (CDB): When you both spoke earlier, I noticed you used the word “anger.” I find that interesting, considering how women are often labeled as angry. The theorist Sarah Ahmed says anger is a fertile emotion, especially for women—something we should celebrate because it can drive positive change, particularly for creative people. So I wanted to ask: Have you ever felt that your identity, as women with Latin American roots, was flattened in how people perceive you and your work? How do you challenge that?

Marisol Mendez (MM): Right now, I’m really drawn to the idea of “intersectionality,” which has been circulating for a while. I like your word, “flattened,” because identity is complex—shaped by where you’re born, where you grow up, even geography. Intersectionality resonates with me because it acknowledges hybrid identities. We contain so many layers. As you said, being women shapes us, but I’m also a white Bolivian, which completely alters my experience. It’s a little sad not to pin down exactly who I am, but maybe that fluidity is beautiful.

Ana Margarita Flores (AMF): I connect deeply with intersectionality too. I was born in Peru but raised in Switzerland, so part of me is Swiss, part is Peruvian. For a long time, I struggled to find my place—until I realized I don’t need just one. Now, I love moving between both and feeling at home in each.

With more Latin American artists gaining visibility, we’re adding layers to the conversation about what Latin America means, especially in Europe. People often stereotype us—assuming we all share the same language, music, or culture. But the reality is far more complex. As artists, our power lies in showing that diversity, even within a single country.

You mentioned anger—it’s a great starting point because it fuels deeper exploration. It pushes me to learn about my culture and challenge simplistic narratives. We’re not trying to erase existing perceptions, but we’re sharing our own stories, offering new perspectives.

CDB: Europeans often act like we’re the only ones entitled to complexity. What you both do so naturally is see things intersectionally—recognizing that reality is layered. You examine patriarchy, colonialism, and womanhood without separating them because they’re deeply intertwined in your work. So my question is: Was there a moment you realized your way of seeing or creating images was influenced by patriarchal or colonial biases? Or that you had to unlearn something within yourself?

MM: I… [response continues]

(Note: The response was cut off, but the rewritten text maintains the original meaning while improving clarity and flow.)I grew up surrounded by machismo and was quite machista myself, coming from a conservative Bolivian background. While my parents weren’t necessarily like that, Bolivia as a whole is more traditional and patriarchal than many places. It’s interesting how these ideas are often passed down by mothers too.

Latin America still has a deeply machista culture—very patriarchal, very traditional. The Catholic Church’s influence is everywhere. Faith is beautiful, and I admire people’s devotion, but the Church’s views on women are restrictive, and even today, many positions of power remain closed to them. Growing up Catholic, these were the lessons I absorbed. I thought I had to be sexy, wear tight clothes, and felt insecure because I didn’t have a curvy figure.

I like the word “deconstruction” because it’s not about erasing these ideas but examining and reshaping them. That’s what I did in Madre. Coming from fashion, I was used to styling and portraits, but in Bolivia, I didn’t have a stylist—so Catholicism became my stylist. I took inspiration from its imagery but flipped the message. For example, I portrayed Mary Magdalene as a trans woman in sexy underwear. Humor, for me, is a way to propose new worlds—turning anger into something playful challenges patriarchal norms.

And it’s important to acknowledge that there are men who’ve helped me unlearn these attitudes. Change is a collective effort; none of us are perfect, and we’re still building new ways of thinking.

Even as a Peruvian, I was afraid of exoticizing my own culture or repeating clichés. I wanted my work to be a love letter to my subjects and my country, showing them respect. To avoid stereotypes, I studied how photographers—not just in Latin America but across the Global South—depicted people, analyzing what worked and what didn’t.

I didn’t want to alter how my subjects looked. Their use of color fascinated me—I’d ask about their daily outfits, and though they wore similar clothes, small changes, like swapping hats or colors, made them unique.

That’s how I began. Collaborating with another director, we reimagined traditional clothing in contemporary, artistic ways. For still-life shots, I drew from fashion campaigns but used traditional shoes. Playing with these elements was my way of redefining fashion on my own terms.

In university, I was told fashion had to involve brands—otherwise, it didn’t count. But who gets to decide what fashion is? If people are wearing it today, it’s fashion. That mindset only reinforced my need to document their style, proving fashion exists beyond commercial labels.You both use clothing to challenge perceptions of reality—one from a colonial lens, the other from a patriarchal one. Since childhood, we’ve been told what’s “proper” to wear and what’s not, just as fashion dictates what’s “in” or “out.”

AMF: My turning point was reading Eduardo Galeano’s The Open Veins of Latin America.

MM: That book made me furious!

AMF: I read it two or three times while researching my final dissertation. There’s a passage where Galeano points out how tourists love photographing Latin American women in traditional dress without questioning its origins. He explains that these clothes—and even hairstyles—were imposed by Spanish colonizers. It shocked me. What we call “tradition” is actually colonial influence, and I’d never questioned it. Further research revealed that hats, too, were tools of control—landowners made their enslaved workers wear different styles to distinguish them.

(Where These Flowers Bloom – Ana Margarita Flores)

MM: In Bolivia, cholitas pasenjas wear bowler hats, which were originally men’s hats. Legend says a shipment of these hats arrived in excess, and since there weren’t enough men to buy them, sellers marketed them to women as high-status European fashion. The women adopted them, not by force, but as a way to navigate the class system.

This is why multiple perspectives matter—history’s often oversimplified when viewed through a single lens. For too long, only certain people were allowed to shape these narratives. Now, with more Latin American photographers telling their own stories, we’re finally seeing diverse voices. So much of our visual history comes from Western outsiders—it’s vital to reclaim our own narratives.

(Bull – Marisol Mendez)

CDB: “Coral” is a word I love. You both collaborate deeply with your subjects—consent and interaction are urgent topics. How did these women inspire you, and how was the work reciprocal?

MM: Photography is about connection. The bare minimum you owe someone is respect, yet it’s often overlooked. I’m nervous being photographed myself—I understand the power imbalance. You’re entrusted with someone’s image; that’s sacred. So I prioritize trust: learning their name, making eye contact, sharing ideas, asking, What do you think? Are you comfortable?

Once, I was working with a non-binary person who’d agreed to a nude shoot but changed their mind. So we didn’t do it—simple. Instead, we made stunning portraits. The person always comes before the photo.

I believe… (text cuts off)The work always grows through collaboration and conversation with the other person. It’s beautiful when they can share their thoughts and feelings—that makes the photograph even better.

Marisol Mendez:

I completely agree. I approach every person with the same intention—I want them to feel happy and proud of the image we create together. I know how it feels to be in front of the camera and see yourself in a photo, so I always keep that in mind.

You have to be aware of the power you hold as a photographer and break it down by making the person comfortable. I like to chat with them before and after the shoot to create a special moment.

Ana Margarita Flores:

I shoot on film, so I can’t show them the results right away, but if I have time, I take a quick phone photo to share. Many of the women I worked with had never been in a photoshoot before, so I started with a small interview to build trust.

What matters most to me is that the person is happy with the image. If they’re not, then I’m not either—I won’t even use it. Collaboration and giving space to the person in front of me is key.

CDB:

Can you share how you organize your work—finding resources, printing, traveling? Any advice for young photographers with similar backgrounds?

AMF:

After university, I applied for a grant in Switzerland, which helped me move to London. Research is essential—I keep a journal of ideas and connections. Even if you’re not in school, watch films, study paintings, gather references. Stay open to possibilities, then ask yourself why you’re drawn to certain ideas.

Trust your gut—it’s there for a reason. No one will tell you if you’re on the right path, but if you follow that instinct and enjoy the process, everything has purpose.

Financially, you have to be creative. I come from privilege, but I’ve also worked hard. Be intentional with savings and where you look for funding.

MM:

Passion and persistence are everything. A long-term project is like a relationship—you have to love it deeply because there will be challenges. Choose something that truly resonates with you, push through difficulties, and stay resourceful.

For me, speaking openly, I returned… [text cuts off]I moved back to Bolivia and lived with my mom, which meant I didn’t have to pay rent—a huge difference. When I first started, my photography didn’t make me any money at all. I worked as a teacher, and I still do because it provides a stable income.

Living in London, I remember the hustle culture—I was working so much that I had no time or energy to create. In Bolivia, I wasn’t in survival mode anymore, so I had more time to focus on my work. But in my city, there were no photography labs. Sometimes I’d wait months just to find film rolls to shoot, and all the film I used was expired.

I worked with my analog camera, using natural light and my mom as my assistant. I made ambitious work with more heart than resources. I tell my students: it’s easy to make excuses—”I don’t have the latest camera, a stylist, or locations.” But if you’re creative, you find a way. If you’re truly passionate, you make it happen.

Behind the scenes of Madre

Ana Margarita Flores (AMF): I love that you described this as entering a long-term relationship—it really is like a full-time job. You have to be passionate. I shot on film and was lucky to be in university, so I didn’t have to pay for developing and printing, which would’ve been expensive. Even now, I find ways to develop my work for free, but I realize how much I would’ve spent without university resources. Students should take full advantage of those facilities—you’ll never have access to those amazing scanners again!

It’s about being resourceful. Even if it takes longer, if this is what you’re meant to do, keep going. Let’s be honest—nobody’s waiting for our work, so take your time and find ways to make it happen.

CDB: Final question. There’s this myth, especially in work environments, that men are better at building connections and solidarity. Can you talk about the people who helped you?

MM: I dedicated my book to my mom because she was with me through the entire project. I called her my assistant, but she deserves more credit than that. Even though she’s not an artist, she knows me and my work—when I was sequencing the book, I’d show it to her.

I’d also share my work in our family group chat and ask my sisters, “We took these pictures—which one’s better?” I’m so grateful for this supportive family. The project wouldn’t be what it is without every woman who participated. I can’t take all the credit—I was surrounded by beautiful energy.

I also had two male photographer friends who helped me a lot. My book editor, a woman, convinced the publisher to make it happen. My writing teacher, an Argentine poet, and Elisa Medde contributed to the book. It was a collective effort of so many women—many eyes, conversations, and voices shaping it.

ANA: For me, it was solitary at first, but when I felt stuck—which happened often—I’d share my ideas with close friends. My housemate, one of my best friends, understood my background because we both grew up in Geneva as Latin Americans. My mom didn’t fully grasp my work at first, but we opened a dialogue that helped me see things differently.

Through PhotoVogue, I met my closest friends today—Bettina [Pittaluga], Delali [Ayivi], Tara [L.C. Sood]. Over the years, we built a safe space where we could openly share our work. Marisol, you know how rare it is to find creatives you truly trust. They witnessed my artistic growth and were crucial in the sequencing…I really valued their input because they have more experience than I do in this area. I felt incredibly privileged and lucky to have their perspectives—not only are they my friends, but I deeply admire their work and find them inspiring. I completely trust their judgment. We spent a full three hours going through my project in detail.

I’m so thankful for PhotoVogue—not only did I meet my best friends through it, but I’ve also connected with other photographers who are becoming close friends. With Marisol, I first saw her work on Instagram, we connected online, then met in Paris and instantly clicked. We reunited again at this year’s PhotoVogue Festival. That’s why PhotoVogue is so special—it creates a space where we can meet and support other amazing women photographers.

MM: I’m really happy we got to do this together today. Like Ana said, the PhotoVogue community truly brings us together. It’s been wonderful meeting all my Instagram friends in person.

CDB: Thank you both so much. Marisol, enjoy your evening, and Anna, have a great day!

AMF: I’m heading to the library today.

CDB: Researching and making connections!