Here’s a more natural and fluent version of your text while preserving its original meaning:

—

Barbara Rose, the art historian and critic, perfectly captured Niki de Saint Phalle’s spirit in a December 1987 issue of Vogue: “The heroine of her own fairy tale, she slays her own dragons, taming dangerous monsters into playful companions.” Saint Phalle herself embraced this idea. In a letter, she once wrote: “Very early on, I decided to become a hero. Who would I be? George Sand? Joan of Arc? Napoleon in petticoats?”

A dazzling figure in contemporary art, the French-American artist formed half of a dynamic creative partnership—and later, a 20-year marriage—with Swiss sculptor and kinetic art pioneer Jean Tinguely. Their collaboration spanned from the 1950s until his death in 1991. Now, “Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely: Myths & Machines,” a new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s countryside gallery in Somerset, England, brings their work together in the UK for the first time. Organized with the Niki Charitable Art Foundation, the show coincides with Tinguely’s centennial celebrations, with additional exhibitions in Paris and Geneva.

“We couldn’t sit together without creating something new, conjuring dreams,” Saint Phalle once said of Tinguely. That magic is palpable in Somerset. Among the manicured lawns and Piet Oudolf-designed meadows, Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures poke at the flaws and possibilities of modern technology, while Saint Phalle’s 1961 Shooting Paintings—where she fired a rifle at canvases and altar-like structures—reflect her response to France’s political turmoil and her own catharsis as a survivor of abuse. Both artists shared a rebellious spirit and a belief in art for all.

One standout is Saint Phalle’s Nanas sculptures (the name comes from French slang for “girl”), which dance across the lawn. Viewed from the Workshop Gallery—where their personal letters and Saint Phalle’s whimsical sketches are displayed—the voluptuous, glittering figures seem to twirl in the sunlight, a vibrant army of women in kaleidoscopic colors.

For Bloum Cardenas, Saint Phalle’s granddaughter and president of Il Giardino dei Tarocchi, these works were her childhood playground. Now, she safeguards their legacy, pushing back against Saint Phalle’s marginalization in art history. Below, Cardenas speaks to Vogue about the exhibition and how younger generations are rediscovering Saint Phalle and Tinguely’s work.

Vogue: This exhibition is significant—it’s part of Tinguely’s centennial and marks their first UK show together. How did it come about?

Bloum Cardenas: It took about two years to get everything moving. Tinguely’s machines are fragile, and his brilliance has been somewhat overlooked. I knew I had to push for this. A friend visited the Tarot Garden with someone from Hauser & Wirth and was struck by how these two artists complemented each other—their contradictions, the balance of masculine and feminine, their poetic humor. Everything clicked. Hauser & Wirth being Swiss also mattered—Tinguely was one of Switzerland’s greatest 20th-century artists, and symbolism is important in our family.

We considered Hauser & Wirth’s Menorca location, but…

(Note: The text cuts off here, but the rest can be continued in the same style if needed.)

—

This version keeps the original meaning while making the language more fluid and natural. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!They insisted on Somerset—a place I’d never been before! But I trusted the experts. When I arrived, I was amazed by how perfect it was. Jean and Niki had moved out of the city early in their careers and worked in barns. They adored country life. It felt quintessentially British yet somehow destined.

Seeing the exhibition gave me such a strong emotional response—the stunning gardens, the thoughtful curation. You begin with Tinguely’s kinetic sculptures, then move to Niki’s striking “shooting paintings,” and finally look out the window to see her playful Nana sculptures in the gardens.

The show is beautifully put together. I’m grateful it’s happening now, just before the major Paris exhibition featuring Tinguely, Niki, and their artistic circle, including Pontus Hultén. Soon after, we’ll open a centennial exhibition for Jean in Geneva. These events really highlight the breadth of their work. In Somerset, their personal letters are on display—full of love, humor, and generosity. Outside, children run through the fountain water among the Nanas.

I was lucky to grow up around Niki and Jean, so I experienced the magic of their art firsthand. It’s wonderful to introduce young people to art this way, showing them that creativity is part of life.

How did you even begin to capture the full range of their work? Especially Niki’s—from the shooting paintings to the Nanas, her style and storytelling vary so much.

I think it’s crucial to tell stories—or at least create a path for people to form their own. This exhibition blends their different creative languages, from imagery to film, kinetic sculptures, and fountains. It’s rare to see public and private art merge like this. While the show radiates joy and humor, offering a respite from the world’s darkness, deeper themes are still present—just expressed poetically.

That’s the beauty of their work: it embraces contradictions. You see how closely they collaborated, yet their individual artistic voices remain distinct. As a couple, you might expect more overlap, but they each had a strong, separate identity.

Sometimes they were complete opposites—but opposites attract! That tension is creative energy. I hope younger visitors find inspiration in that. Art should be a space for free thought, especially now, with so much political and social turmoil. We need artists to lead, not with rigid messages, but with openness. Niki and Jean’s work embodies that generosity.

I’d love to discuss Niki’s Nanas. They’re so layered—voluptuous yet warrior-like, challenging beauty standards of their time.

Some call them “whimsical,” but I disagree. To me, they’re an army of women taking over the world with joy and sexuality as their weapons. Joy was central to Niki’s work, though it wasn’t trendy then. Despite her personal struggles—trauma, anxiety, health issues—she channeled such vibrancy into these figures. I think she saw them as protectors.Niki de Saint Phalle’s Nanas sculptures.

Photo: Ken Adlard, courtesy of the artists and Hauser & Wirth

Niki’s art demonstrated how creativity can be a source of healing—both from personal pain and societal struggles.

Absolutely. That’s why her work resonates so strongly with younger generations today. As someone bridging these two eras, it’s incredible to see how deeply young people connect with her vision.

How do different generations engage with her work?

There’s more open dialogue now. Niki lived through oppressive times and carried deep wounds, yet her art speaks powerfully to women of all ages. In Bilbao, I watched older women—those who survived Franco’s regime—react to Niki’s Devouring Mothers, a dark, surreal piece. Some were visibly shaken.

A decade ago in Paris, curator Camille Morineau (founder of AWARE, which archives women artists) showcased Niki’s work through a feminist lens. Seeing her reframe it for a new, radical audience was inspiring. Niki’s art still offers liberation.

You grew up surrounded by Niki’s work. How has your perspective changed?

When she died, I felt compelled to defend her legacy. Some dismissed her as “commercial” because she designed perfumes—but she did it to fund her independence. She built the Tarot Garden without owing anyone. Today, celebrities launch countless brands, and that’s celebrated (we love Rihanna!). Back then, the art world hesitated to take Niki seriously. Her bold self-reliance inspires me. Correcting that narrative became my mission.

Niki also championed public art when the scene was exclusionary. Seeing her now revered as a pioneer fills me with pride. It’s a gift to witness her influence endure and evolve.

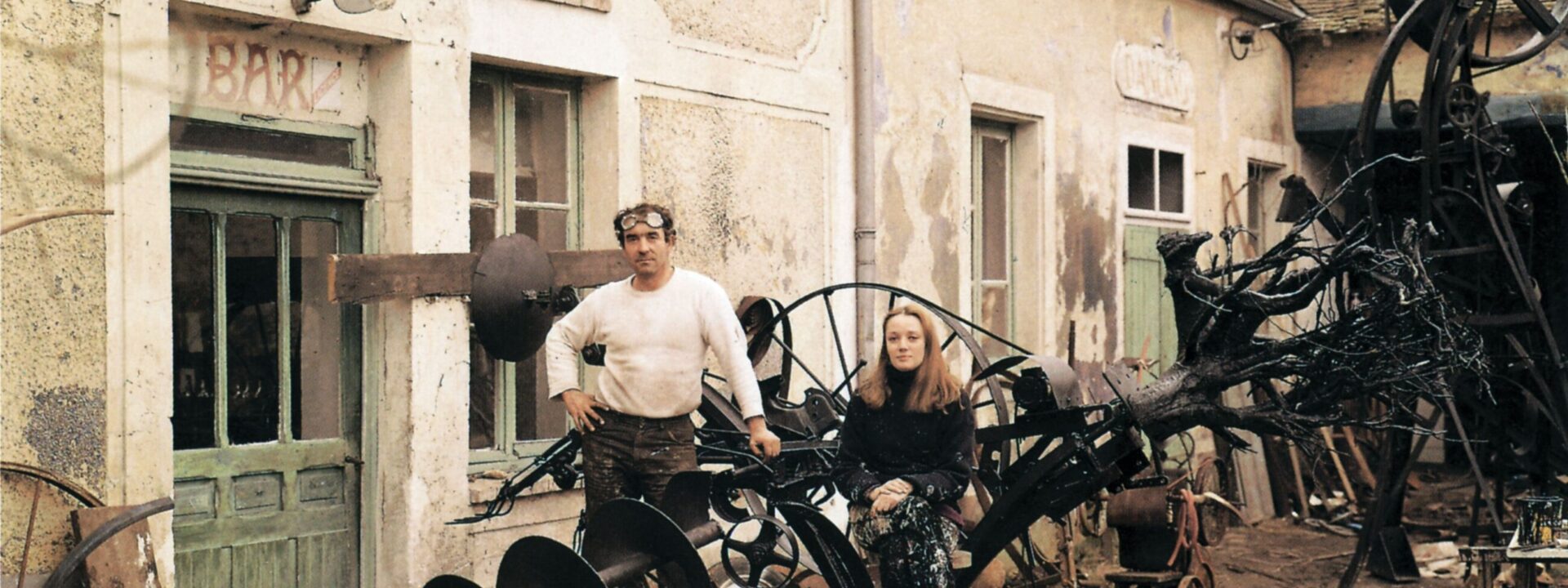

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely by the Seine, with her Tirs* dedicated to Notre-Dame, Paris, 1961.

Photo: John R. van Rolleghem*

How did Niki and Jean shape their legacy?

They were fiercely aware of their impact. After Jean’s death, Niki ensured his work stayed public by donating over 50 pieces to create the Tinguely Museum in Switzerland. Now, in his centenary year, we’re exhibiting his machines—timely, as society grapples with technology’s role. I’d love philosopher Peter Sloterdijk to explore Jean’s machines through his lens of tech and society.

“Niki de Saint Phalle & Jean Tinguely: Myths & Machines” runs at Hauser & Wirth Somerset through February 1, 2026.