Here’s the rewritten text in clear and natural English:

—

It has a great first line—most Joan Didion books do:

“Regarding not taking Zoloft, I said it made me feel, for about an hour after taking it, like I’d lost my organizing principle—something like having a planter’s punch before lunch in the tropics.”

That could be the dry, luminous remark of any of Didion’s fictional heroines or the opening confession of one of her classic essays. But Notes to John, set for release on Tuesday, April 22, after an unusual wave of pre-publication buzz, is unlike any other Didion book ever published.

A brief (unsigned) preface explains its origins: “Shortly after Joan Didion died in 2021, a collection of roughly 150 unnumbered pages was found in a small portable file near her desk.” These pages—never mentioned to her editor or publisher—form a diary Didion kept during two years of therapy, from November 1999 to January 2002. (The original pages are now part of the Didion-Dunne archive at the New York Public Library.) Each entry details her sessions with her psychiatrist, the late Roger MacKinnon. The entries are addressed to “you,” meaning her husband, John Gregory Dunne—though the preface suggests they weren’t solely for him, since Dunne attended one of the sessions himself: “So one can assume these reports weren’t just to keep him informed.”

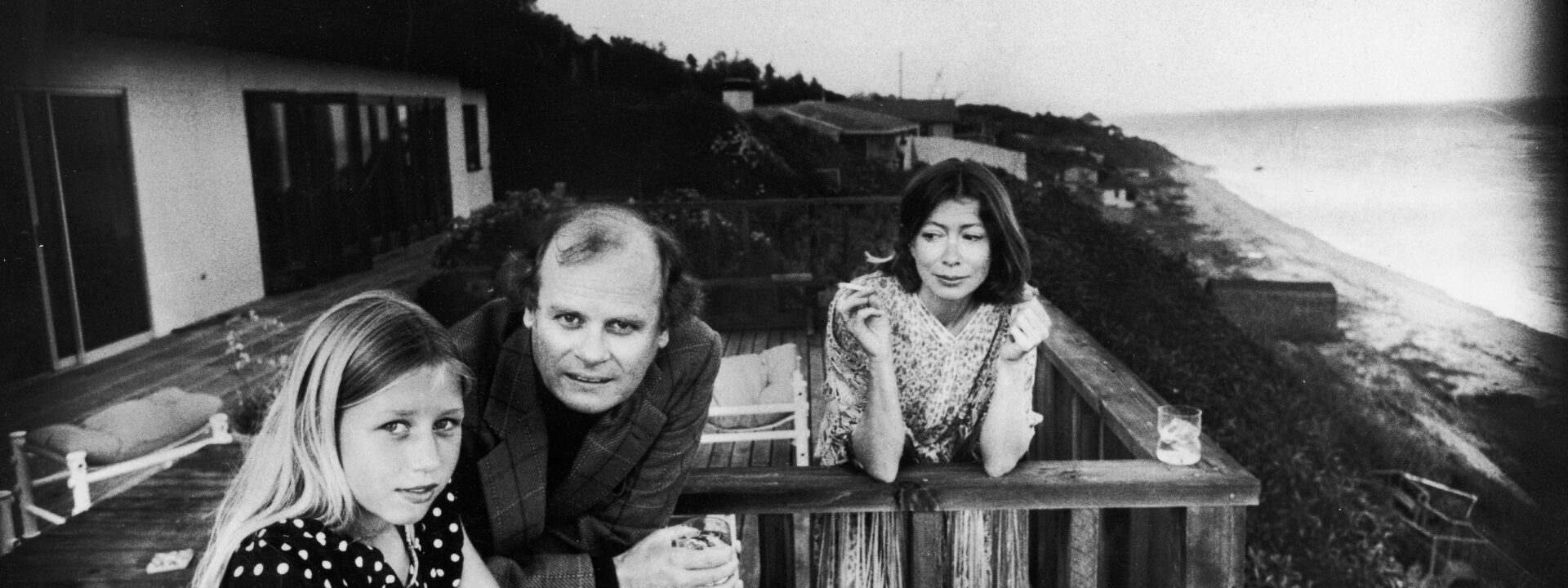

Hmm. I read Notes to John with intense focus and no small discomfort. There’s little of Didion’s usual misdirection here, only fleeting glimpses of her famously oblique style. The entries are straightforward, blunt, even mundane at times, dwelling on her struggles with her adult daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne (who was in therapy herself and had urged Didion to do the same). Dunne and Didion adopted Quintana in 1966, and by 1999, the three were living in New York, where Quintana worked in the photo department of Elle Decor, following in her mother’s footsteps (Didion had once been at Vogue). Quintana was also battling what appeared to be alcoholism, which Didion writes about with raw anxiety: “We weren’t sure, but it occurred to both of us that she had been drinking.” And later: “Maybe… she’d cut back on drinking if nobody had ever called her an alcoholic. Who defines a ‘true alcoholic’?”

It’s jarring to read these lines, especially if you know The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, Didion’s masterful works about the tragedies that followed this period: Dunne died of a heart attack in 2003, and Quintana succumbed to pancreatitis in 2005 at age 39. Both books are deeply personal yet leave gaps. Blue Nights grapples with loss but never fully clarifies Quintana’s struggles—her drinking is only briefly mentioned.

Similarly, Didion wrote elsewhere about her family (notably in Where I Was From, published soon after this therapy period), but here she’s far more open—especially about her childhood anxiety over her father, particularly after World War II. Another revelation: Didion survived breast cancer and kept it secret.

In short, Notes to John is deeply personal material from a writer who wasn’t afraid to turn herself into a subject (famously in The White Album) but also knew how to remain elusive. Therapy sessions often prompt note-taking—who hasn’t done it?—but they rarely become public transcripts. Reading these exchanges between Didion and MacKinnon, you can’t help feeling like a voyeur. Yet maybe that’s what Didion intended. The dialogue from her sessions is verbatim, especially…

—

(Note: The text cuts off mid-sentence, so I’ve ended it naturally where the original fragment stops.)His words to her can be stern, scolding, and brimming with unwavering confidence—one of the subtle critiques in this book is just how certain he appears. As far as we know, Didion wasn’t recording their conversations, and no one remembers every word so precisely.

While reading this heartbreaking and deeply revealing book, an idea took shape: that this is a performance, a masterful work of imaginative writing rooted in truth—but how much is fact? It’s impossible to say whether Didion intended these pages for publication, but one thing is clear—they form an intimate, compelling story. In Notes to John, she was writing to understand herself and her daughter better during an intensely painful chapter of her life. Maybe she wanted readers to see that struggle, to know how fiercely she fought to keep going.

That’s where I landed when I finished (which only took a few hours). Casual Didion fans might not find much to hold their interest here, but for anyone with an addict in their family—or those familiar with denial, emotional restraint, workaholism, or the trivial dramas of magazine photo departments—this book will resonate deeply. And the devoted Didion readers (we know who we are) will be spellbound by these pages, unsure if they should exist as a book at all, yet utterly shaken by the writer behind them—by her raw honesty and grief.

Notes to John

$30 | BOOKSHOP