In the June 1, 1943, issue of Vogue, nestled in the “People Are Talking About” section, a striking photograph appeared: Gala Dalí, poised in front of one of her husband’s dreamlike paintings, captured by Horst P. Horst. “No painter at all, merely a spiritual collaborator,” the caption read, acknowledging Gala’s pervasive influence on Salvador Dalí’s life and work. The magazine—and the art world—was captivated by her mystery, her elegance, not to mention the fact that some of Salvador’s paintings bore her name.

Gala Dalí in a full-length skirt, standing with a staff.

Photographed by Horst P. Horst, Vogue, June 1943.

Born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova in Kazan, Russia, Gala lived many lives: muse, lover, wife, and mythmaker. Before becoming Madame Dalí, she married the French Surrealist poet Paul Éluard and was entangled with Max Ernst. She moved through the art world with unmatched authority, unsettling entire cities—Paris, Figueres, New York—with her calculated, often scandalous presence. Her image, like Dalí’s mustache, became part of the spectacle. But who was Gala, truly?

In Surreal: The Extraordinary Life of Gala Dalí, author Michèle Gerber Klein (Charles James: Portrait of an Unreasonable Man) seeks to answer that very question. “Gala Dalí was neither a miser nor just a vixen,” Klein explains. “I tried to portray her as a real human being, not just a sound bite.” The result is the first deeply researched biography of a woman long eclipsed by the men she inspired. Drawing on untranslated diaries, previously unexamined archives, and interviews with Gala’s granddaughter and former confidantes, Klein restores depth and agency to a figure often reduced by history.

Surreal begins not with Gala’s death but with one of the most dazzling—and bizarre—episodes of her life. It’s 1941, and the Dalís, newly arrived in the U.S. after fleeing Europe, are staying at California’s historic Hotel Del Monte. That September, they host a Surrealist benefit unlike anything America had seen: the ballroom is transformed into an enchanted forest, complete with papier-mâché animal heads, mannequins, squash, and pumpkins, as if plucked from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. At the center of it all is Gala, reclining on a red velvet bed in a unicorn headdress, a lion cub curled in her lap.

Though technically refugees, the Dalís command attention with theatrical defiance. Life magazine sends a reporter. Bob Hope is served live frogs under a cloche. And Gala—graceful, elusive, otherworldly—reigns as one local paper dubs her, “the princess of her enchanted forest.” It’s a scene worthy of Dalí’s brush, but it’s Gala who orchestrates it all.

Yet she remained an enigma. “Gala said, ‘The secret of my secrets is that I don’t tell them,'” Klein notes. But in Surreal, the veil lifts—just slightly—revealing the extraordinary life of a woman who refused to live by ordinary rules.

Vogue: What first drew you to Gala Dalí as a subject? Was there a moment when you knew her story had to be your next book?

Michèle Gerber Klein: I was having lunch with Michael Stout at La Grenouille—where he used to dine with the Dalís when he was their lawyer in the 1970s—and he shared stories about Gala, saying, “You should write about her. She was a fascinating woman.” So I did.

Vogue: You’ve called this the first serious biography of Gala. How does Surreal reshape our understanding of her?

Klein: Gala Dalí was neither a miser nor just a vixen. I wanted to portray her as a real person, not a caricature. Of course, no one can fully know her private thoughts, but I aimed to uncover as much of her complex personality as possible.

Vogue: How did you research someone so enigmatic—and so mythologized? Were there…Were there any unexpected discoveries in the archives that changed how you saw Gala’s story?

I focused on primary sources—reading her memoirs, accounts from people who knew her, and interviews with her childhood friends, former lovers, and even her granddaughter, who had never been interviewed before. I also spoke to Dick Cavett, who once interviewed Dalí and his pet anteater on his show—with Gala selecting her husband’s outfit for the occasion.

I visited the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation in Figueres, Spain, where I examined her collection of couture dresses, including pieces she designed herself or had replicated by her dressmaker. I sent photos to the Costume Institute for verification. I also combed through letters and documents at the foundation and had several conversations with its director, Montse Aguer, comparing our perspectives on Gala. To better understand her emotional bond with Dalí, I even consulted a psychiatrist.

Spanish artist Salvador Dalí and his wife and muse Gala Dalí sitting outdoors on a hill, c. 1948. Photographed by Horst P. Horst.

How have her descendants responded to your book?

Her granddaughter, Claire Sarti, baked me a cake.

Gala lived many roles—muse, wife, collector, intellectual. Which did you find most fascinating to explore?

Her story is both a love story and a tale of brilliant self-marketing. She was also a woman of extraordinary style, favoring designers like Schiaparelli, Chanel, and Dior. She actually knew Dior before he became famous, back when he worked at the Pierre Colle Gallery, which represented Dalí in 1930s Paris.

What was the hardest part of writing about Gala? Was there any aspect of her life that remained elusive?

Many people wrote harsh things about her, often out of jealousy or misunderstanding, so separating fact from fiction was both difficult and intriguing.

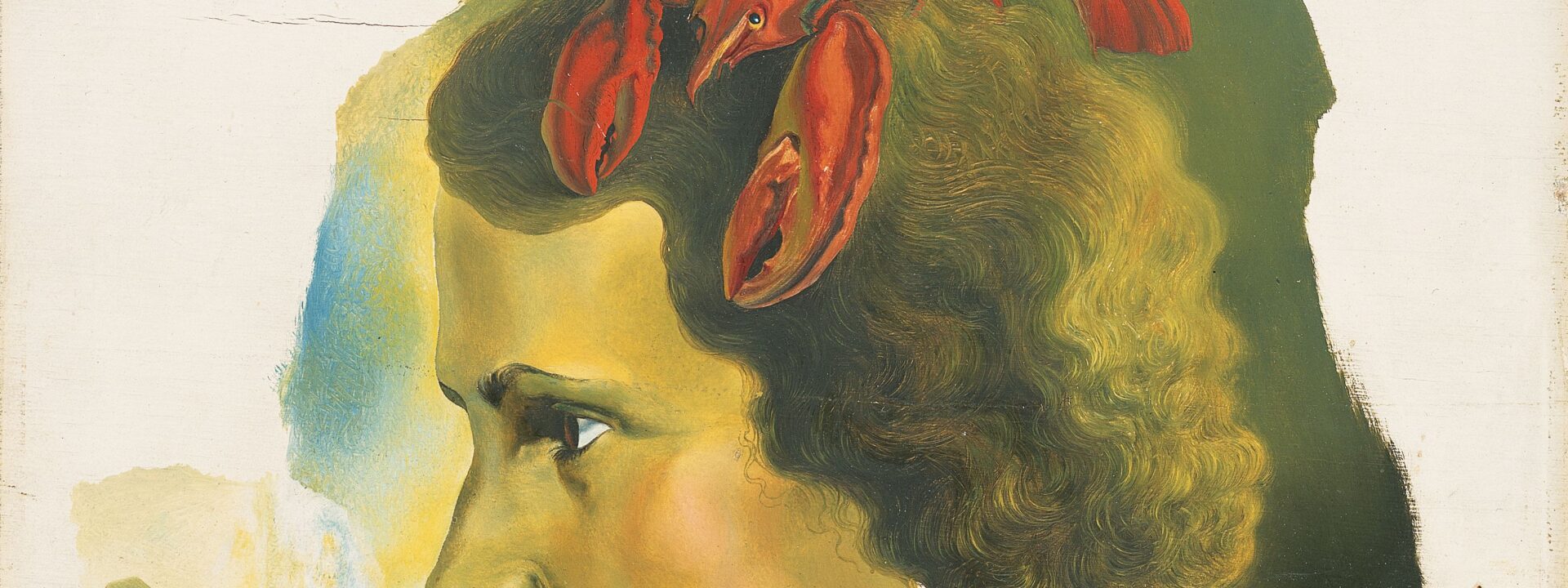

Gala Dalí wearing the Shoe Hat and Lips Jacket, inspired by her and designed by Elsa Schiaparelli in collaboration with Salvador Dalí, 1938. Photograph by André Caillet. © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala–Salvador Dalí, Figueres, Spain.

Gala is often reduced to being Dalí’s muse, but you present her as far more. What do you think was her greatest contribution to Surrealism?

When Gala met Dalí in 1929, she meticulously documented their conversations. The next year, she compiled these notes into The Visible Woman—a poetic, artistic, and theoretical work arguing that fantasy is reality. Though it was framed as Dalí’s artistic statement, he admitted to his sister, Anna Maria: “Gala is the writer in our family.”

Some describe her as manipulative, others as visionary. How do you reconcile these conflicting views?

She wasn’t manipulative in the usual sense. The Dalís were performance artists—everything they did was intentional, part of their creative expression.

What do you hope readers—especially women—take from Gala’s life?

The most important lesson is to have the courage to be unapologetically yourself.

What’s next for you? Are there other overlooked women in art history you’d like to spotlight?

As Gala would say: “The secret of my secrets is that I don’t tell them.”

Surreal: The Extraordinary Life of Gala Dalí

$30 | BOOKSHOP