The day after presenting his elegant and effortlessly wearable Fall-Winter 2025 women’s collection in March, Rick Owens was spotted walking home from Paris’s Basilica of Saint Clotilde, holding fragrant white jasmine he’d picked from nearby bushes. This church holds special meaning for him—he visits often, sometimes alone, sometimes with his longtime assistant Anna-Philippa Wolf (known as AL) and her baby. He describes it as “an extension of my home, part of my life in Paris… a perfect little place.”

Though not religious himself, Owens appreciates what churches represent. “At their best, they’re spaces where people come together to create a system of mutual care,” he reflects, then adds pointedly: “At their best.” Saint Clotilde holds particular significance—it’s where he and his parents would discuss end-of-life matters during their visits for fashion week. (“Dad wasn’t religious—never was—but Mom was Catholic.”) Now that his parents are gone, these walks through Paris’s 7th arrondissement—between the church, his home and headquarters at Place du Palais-Bourbon, and across the Seine to the Louvre and Palais Royal—inevitably turn his thoughts to mortality. “I suppose this is where I belong now,” he muses. “This is the street where I’ll grow old, where waiters will sigh at me always ordering the same thing.” After more than two decades, the California native who once adored Venice’s Lido has fully embraced Paris as home.

Paris has embraced him right back. On June 28, the Palais Galliera—the city’s premier fashion museum—will open “Temple of Love,” a retrospective of Owens’ work. This marks a rare honor: the museum has only showcased living designers like Azzedine Alaïa and Martin Margiela before him. The recognition is well-deserved. Owens’ career defies fashion industry norms—maintaining complete independence for decades while growing more influential each year, captivating everyone from fashion intellectuals to global skate goths. His unique blend of bold aesthetics, sharp intelligence, fearless experimentation, and relentless work ethic has outlasted luxury industry trends and naysayers alike.

“I know I’m unusual in fashion’s revolving door of designers,” Owens acknowledges. “I was just lucky to find partners”—referring to his wife Michèle Lamy and Owenscorp’s Luca Ruggeri and Elsa Lanzo—”who’ve fiercely protected me for 30 years. Their talent matters as much as mine. Other designers must envy that. I’ve been very, very lucky.”

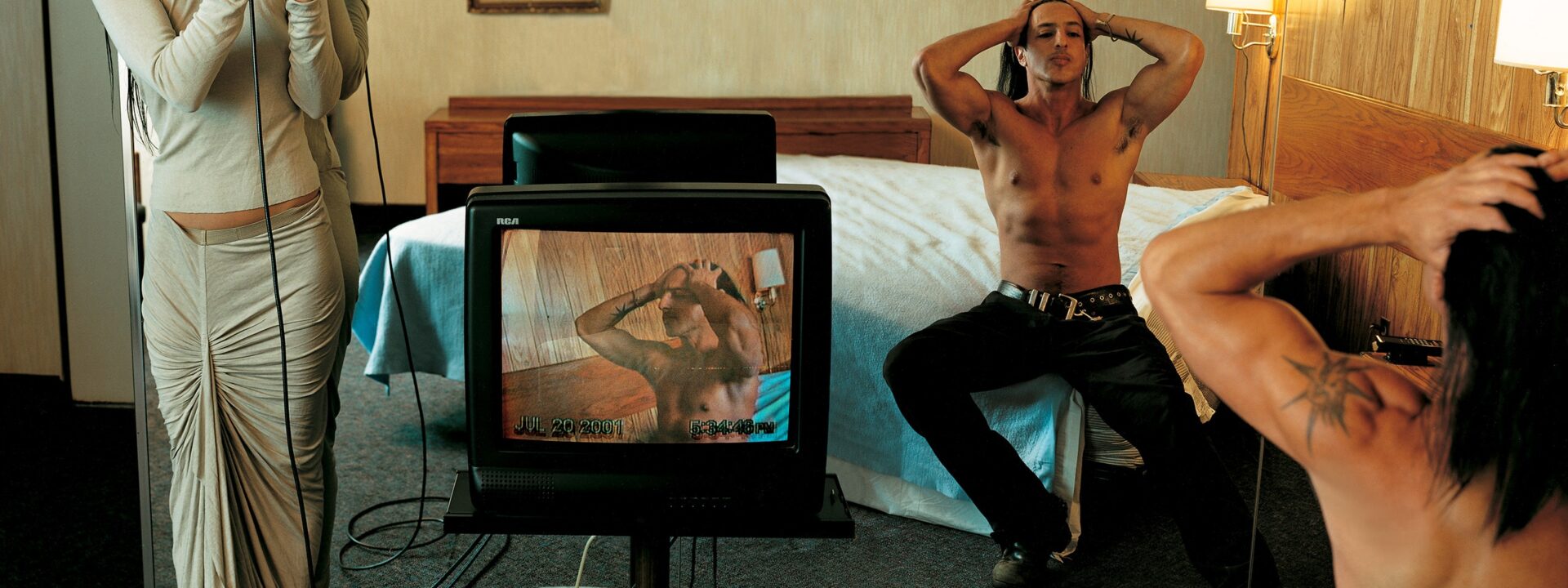

Curated by Alexandre Samson (behind 2023’s acclaimed “1997 Fashion Big Bang”), the Palais Galliera exhibition will trace Owens’ Paris years through his namesake label, his transformative work for fur house Revillon (which brought him to Paris in 2002), his Fortuny collaboration (nodding to Venice’s importance in his life), and early Los Angeles pieces—including recreations of Lamy’s iconic LA wardrobe and their massive platform bed (the origin of Owens’ now-legendary furniture line, overseen by Lamy and owned by fans like Travis Scott). Hundreds of his signature threadbare “spiderweb” tees… [text continues]In those early years, alongside his runway showstoppers—think Mad Max meets Madam Satan, with sharp-shouldered, sinuous designs in leather, silk, and jersey that blended Brutalist structure with romance—Owens stripped things down to their essentials. (“Can we skip the full looks?” Owens recalls asking Samson. “This simplifies everything.”)

The exhibition will feature album covers by David Bowie, Klaus Nomi, and Iggy Pop, with a soundtrack ranging from the Sisters of Mercy to Gustav Mahler. There will also be draped eveningwear that defies easy explanation—imagine Madame Grès on the moon. (“Will I ever recreate that in my lifetime?” Owens muses, genuinely curious.) A restricted-access “Joy of Decadence” room will house the life-sized statue of the designer urinating, first displayed in Florence in 2006—not for the faint-hearted or young visitors.

Despite its eclectic mix, the show aims to highlight Owens’ technical mastery as a patternmaker, cutter, and draper, while showcasing his classical influences. “I want people who think they know Rick Owens to discover his cultural depth,” says Samson. “It’s deeply rooted in French culture. There’s so much more to him than just rebellion.”

Owens hopes visitors leave with a sense of the kindness and gentleness behind his work—qualities often overshadowed by perceptions of darkness or doom. “I like championing softer values,” he says. “Inclusivity sounds cliché now, but the world I’ve built is meant to welcome everyone.”

To truly grasp Owens’ vision, you have to see through his eyes. When he sent 200 models and students marching in unison around the Palais de Tokyo—as he did for his groundbreaking Hollywood men’s show—it was a nod to the devoted fans who wait outside his shows season after season. His Spring-Summer 2016 women’s show, where models carried others on their backs, questioned the relevance of stilettos: “How can I reinvent physicality?” he asks. “How can I create spectacle without excess?”

The retrospective traces his journey—from a Hollywood club kid in survivalist gear to a flâneur who strolls through church gardens with his toddler, admires his wife’s grace, and deeply misses his parents.

“Inclusivity is seen as corny now,” Owens reflects, “but I’ve always aimed for it. The irony? Once you reach a certain level, people gatekeep your world. It becomes a fortress. You can’t win.”

The bigger irony is that today, inclusivity isn’t just aspirational—it’s an act of defiance in a world growing more corporate and homogenous. Owens often expresses his unease walking through airport duty-free zones, where the same idealized faces stare back from every ad. “There’s a rigid standard of beauty,” he says. “I don’t reject it—it’s fine. My role is to offer alternatives.”