For fans of John Singer Sargent, lovers of the Gilded Age, and fashion historians, the story of Madame X’s scandalous debut at the 1884 Paris Salon is legendary. When the 28-year-old artist captured the striking beauty of Madame Pierre Gautreau—a fellow American in Paris—he painted her exactly as she was, from her auburn updo and distinctive nose to her pale lavender skin and form-fitting black dress, its jeweled strap slipping off her shoulder.

But the painting caused an uproar, with critics attacking both the portrait and Gautreau’s already controversial reputation. Though Sargent later repainted the strap to sit properly on her shoulder, the damage was done.

After keeping the painting for over 30 years, Sargent—who eventually settled in London—sold Madame X to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1915, where it remains a star attraction. “It’s a portrait that captivates people—they’re always drawn to it and want to know more about her,” says Stephanie L. Herdrich, The Met’s curator of American painting and drawing. Over the years, Herdrich has become an expert on Sargent, jokingly calling herself Madame X’s “caretaker, travel companion, and PR rep.”

“Even though people think they know the painting’s story,” she adds, “I felt there was more to say.”

Originally, Herdrich planned an exhibition focused solely on Madame X, aiming to present a deeper, more nuanced account of its creation and impact. But over six years, the idea grew into Sargent and Paris, a sweeping showcase of the artist’s defining decade in the French capital, culminating in his 1884 masterpiece. Running from April 27 to August 3 at The Met, the exhibition was organized with Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, where it will travel later this year. (Coinciding with the 100th anniversary of Sargent’s death, it marks the first major French exhibition of his work and the first time Madame X has been shown in France in over 40 years.)

“Thinking about a show that suited both institutions, Sargent’s early career in Paris—a pivotal time for him—felt like the perfect fit,” says Herdrich. She notes that the Musée d’Orsay owns remarkable Sargent works like La Carmencita (1892), one of the first paintings by an American artist bought by the French state and the first Sargent portrait to enter a public collection. “Sargent is far less known in France than in America,” she adds, “so this is also a chance to introduce him to new audiences.”

Even longtime Sargent admirers will find surprises: the exhibition features around 100 works, including some of his most celebrated pieces from collections worldwide. “Many of these are among the most treasured works in their lenders’ holdings,” said Max Hollein, The Met’s director, at a preview.

The show begins with Sargent’s early portraits and still lifes, created when he was an 18-year-old art student in Paris.John Singer Sargent was born in Florence in 1856. The exhibition highlights his artistic influences, from Old Masters like Velázquez and Frans Hals to contemporaries such as Monet, Rodin, and Helleu. Later galleries showcase his landscape and architectural works from his travels across Italy, Spain, and Morocco, alongside portraits of Parisian women that redefined modern portraiture.

One notable piece is London in the Luxembourg Gardens (1879), an oil painting now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“People may be surprised by how prolific and bold Sargent was in the 1870s and 1880s,” says Herdrich. “While his lavish 1890s portraits are famous, his early work is even more daring—he was experimenting and refining his style.”

Sargent’s boldness is most evident in Madame X. “It was an ambitious project,” Herdrich explains. “He sought out Madame Gautreau, fascinated by her striking profile and powdered complexion, and created numerous preparatory sketches to capture her unique beauty.”

Despite being displayed anonymously at the Salon as Madame , the subject was quickly recognized. Some critics found the portrait unflattering, while others resented Gautreau herself—a Louisiana-born socialite who had risen in Parisian high society.

“She was famous for her beauty but always seen as an outsider,” Herdrich notes. Many disapproved of her family’s wealth, built on plantations worked by enslaved people. Research also revealed her proximity to French political elites, fueling further resentment. One journalist even complained that Americans like Sargent and Gautreau were stealing French accolades and attention.

Though the painting’s revealing neckline and fallen strap caused outrage, the same Salon featured other risqué artworks—often excused as allegorical. To highlight this double standard, the exhibition includes reproductions of other works from that year, along with satirical cartoons and reviews.

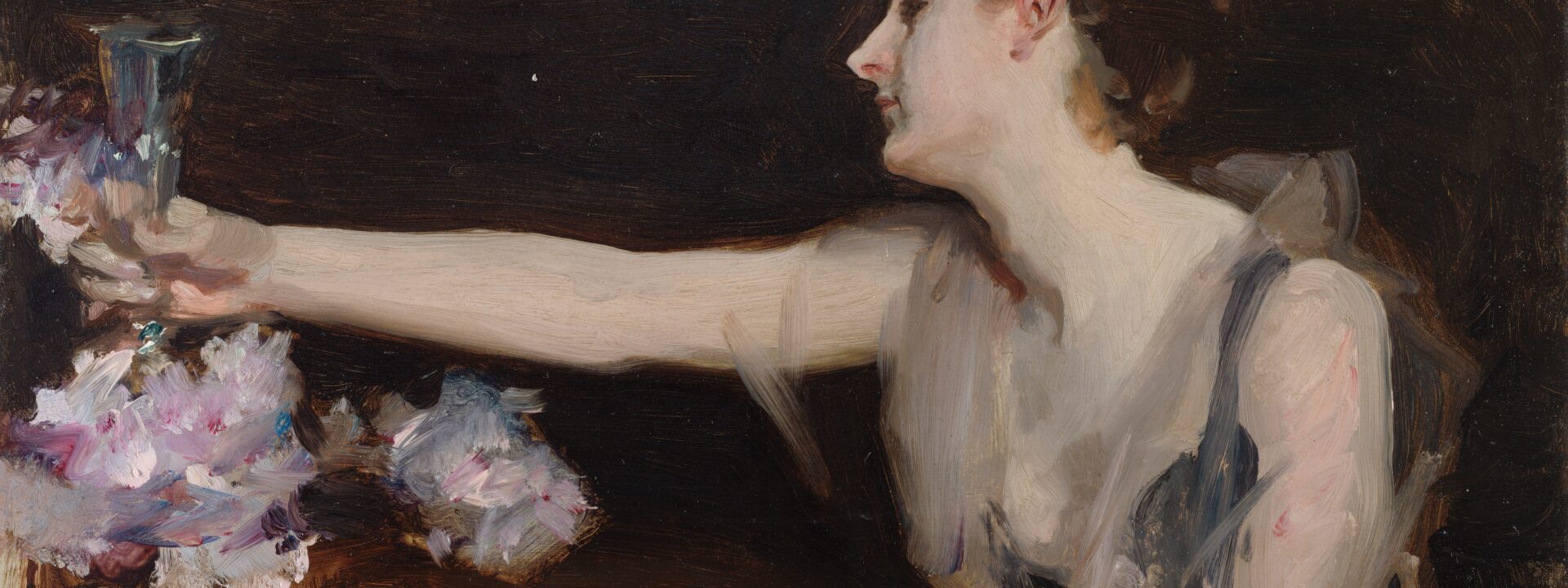

Also on display is Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast (1882–1883), an oil sketch now at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

—David MathewsPozzi at Home, 1881. Oil on canvas. The Armand Hammer Collection, Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Even after Gautreau’s death, the rumors persisted. In the 1950s, a Sargent scholar claimed that the American socialite, married to a French banker, had an affair with her gynecologist, Samuel-Jean Pozzi—the subject of Sargent’s famous portrait in a crimson cloak (also featured in Sargent and Paris).

“That’s one rumor I really want to debunk,” says Herdrich. “Both portraits are stunning and full of sensuality, but there’s no solid evidence to support the affair. By keeping this rumor alive—often by displaying the two portraits near each other—we risk diminishing Madame Gautreau’s reputation. It also undermines Pozzi’s legacy as a groundbreaking surgeon.”

When Madame X was first painted, the sitter believed it was a masterpiece. “She was fully committed,” Herdrich explains. “But both she and Sargent underestimated how society would react.” In a letter to The Met’s director when selling the painting, Sargent called Madame X “the best thing I’ve done.”

Though his fame soared despite the backlash, Herdrich notes that after Madame X, Sargent became “more cautious about pleasing his patrons.” This makes his earlier works some of his most daring and expressive. “Sargent’s art feels familiar now, but at the time, it was truly pushing the limits of portraiture.”