My oldest sister, Selena, was 27 when I was born in 1954. By the time she was 30, she and her husband John already had eight kids. My nieces and nephews were closer to my age than my own siblings, and they became my closest friends. The lively energy of Selena’s house surrounded me—full of music, excitement, and warmth. The voices of her five daughters and three sons filled the air: Deanne, Linda, Leslie, Elouise, Elena, Tommie, Ronnie, and Johnny. Don’t bother trying to keep them all straight—even Selena couldn’t.

Johnny, my nephew, was four years older than me and my very best friend. Asking me about my earliest memory of him is like asking when I first realized I needed air or water—he was just always there. Ronnie and I would get into fistfights at least once a week, squaring off like little warriors, but Johnny would step in.

“It was funny, Tenie,” he’d say, using my nickname, trying to make me laugh. And maybe it was funny—but only because Johnny said so. He was the boss, and we all knew it. Even at nine years old, he ran the show.

But as strong as Johnny was in our family, the outside world could be harsh. Growing up in Galveston, Texas, Johnny was openly gay—he never hid who he was. Selena had filled him with so much love and confidence that he never felt the need to. Still, strangers would whisper, grimace, or shoot him judgmental looks. And when they did, I glared right back.

Johnny listened to all my wild stories—how I skinned my knee, how I tried to breathe underwater to become a mermaid (and just ended up sick). He’d shake his head and call me “Lucille Ball,” stretching out the “Lu” as he laughed at my latest misadventure. With Johnny, all my big feelings and endless energy had a place to land. It was my honor to be his protector—to hand him the flower he’d tuck behind his ear.

When I told him about my struggles at school, he understood in a way no one else did. He knew what it was like to be told, over and over, that you didn’t fit in outside our family.

After I turned six, we all prepared for Johnny’s tenth birthday—double digits. But something about him turning ten made my brothers nervous. Johnny was as confident as ever, and no one in our family ever told him to “act less gay.” Still, my brothers knew how cruel middle school boys could be, and they worried.

They had found their place in sports, so with good intentions, my brothers—Tommie and Ronnie included—decided Johnny should play basketball. He went along with it, and I tagged along to the court at Holy Rosary, sitting cross-legged on the sidelines. Johnny tried, running around in his own way—no tough-guy act. When he shot the ball, he’d let out a loud “oooh,” somewhere between Lena Horne and his usual self, using humor to keep his dignity.

“Man up, Johnny!” one of my brothers called. “Man up!”

“Get the ball and shoot it,” Ronnie said. They’d never talked to him like that before, but this was their court language. They’d convinced themselves Johnny needed to learn it too.

Johnny looked down for a second, then quietly said, more to himself than anyone, “I don’t like this at all.”

That was it. I jumped up like I was saving someone from a train—dramatic as ever.

Johnny and I went straight to my mother, and I launched into how they’d forced him to play when he didn’t want to. “They were making fun of him!”

“Were they, Johnny?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “Not really. I just don’t like basketball.”

My mom paused. “Her—””Come.” She gestured toward her sewing table and let him take her chair. This was her “fixer” mode—those quick, efficient movements she made when tackling a project. “Johnny, if you make clothes for people, they’ll adore you. They won’t make fun of you.” She understood what school bullies were capable of, and she knew he needed armor. Taking his hands, she guided him through the motion of a stitch. “I know you have an imagination,” she said. “You make clothes for them? They’ll do anything for you.”

She taught him to sew, and Selena gave him a daily masterclass. Sewing opened doors, letting him bring the clothes in his head to life. Even as a child, he crafted exquisite pieces. By the 1960s, he was wearing the boldest fashions—first for the family, then for strangers who’d stop us on the street and ask, “Where’d you get that?” And yes, his talent made people adore him. The coolest guys came to him for custom clothes, paying in cash and protection. No one ever mocked him, and he entered his teens safe—all we ever wanted for him.

When Johnny turned 18, he started going to a club called the Kon Tiki. He took me to my first drag show there, and I was hooked. He befriended the queens, began designing their costumes, and became the go-to person for crafting unforgettable looks—showstopping beauty with the meticulous detail Selena had taught him.

By then, Johnny had saved enough that when Selena’s upstairs neighbors moved out, he took over the rent for the duplex’s second floor. The two floors shared a staircase, and from Selena’s place, you could watch the parade of Johnny’s visitors. Selena’s husband—Johnny’s dad—would scratch his head, baffled. “Tenie, you know them boys went up there,” he’d say, “but they ain’t never come down. Just those girls.”

I started helping Johnny with hair and makeup upstairs, too. More often than not, I’d look at one of his clients and think, I could do this even better. I’d have a vision, and we’d style the wigs together. I loved that moment in the mirror when someone’s transformation clicked—when you’d made them look extraordinary while somehow revealing their true essence.

As I prepared for my senior year, I began counting the months until graduation and my escape from Galveston. I didn’t know where I was headed, but now that Johnny had found his people, I needed to find mine.

Editor’s note: In 1990, Tina’s nine-year-old daughter, Beyoncé, began singing with a group called Girls Thyme, which later became Destiny’s Child.

With Destiny’s Child constantly touring, it was easy for Johnny to hide how sick he was getting. He started having erratic episodes, which made him withdraw from the family. Then came the hospitalization—Selena found out first. Johnny was her heart, her best friend. She called me immediately, and I caught the next flight to be with him. The diagnosis was AIDS-related dementia, causing delirium and paranoia.

Medication helped briefly, but not for long. He began losing motor control. We moved him into a long-term care facility—not quite a nursing home, but close. The staff was kind but clear: this would be Johnny’s home until hospice.

When the family wasn’t traveling with Destiny’s Child, I’d bring Johnny home on weekends to spend time with Solange and Beyoncé. Saturday mornings, my daughters would blast the house music he’d played while helping raise them. Now they played it for him.I remember Johnny dancing around, bobbing his head to Robin S singing Show Me Love or Crystal Waters’ la da dee, la do daa. My mother would take his hands and guide him through sewing a stitch. “You make clothes for them? They’ll do anything for you.”

Solange was 11 and would go all out to make him laugh, pulling silly faces just to hear him chuckle. She’d even fetch his “funny cigarettes,” and they’d sit on the little patio where I let Johnny smoke weed because it helped with his nausea. I used to lecture the girls about it, not wanting him to smoke around them, but now, we had bigger things to worry about. Watching Johnny fade was hardest on Solange—she feels things deeply, absorbing pain until it later resurfaces as art or words.

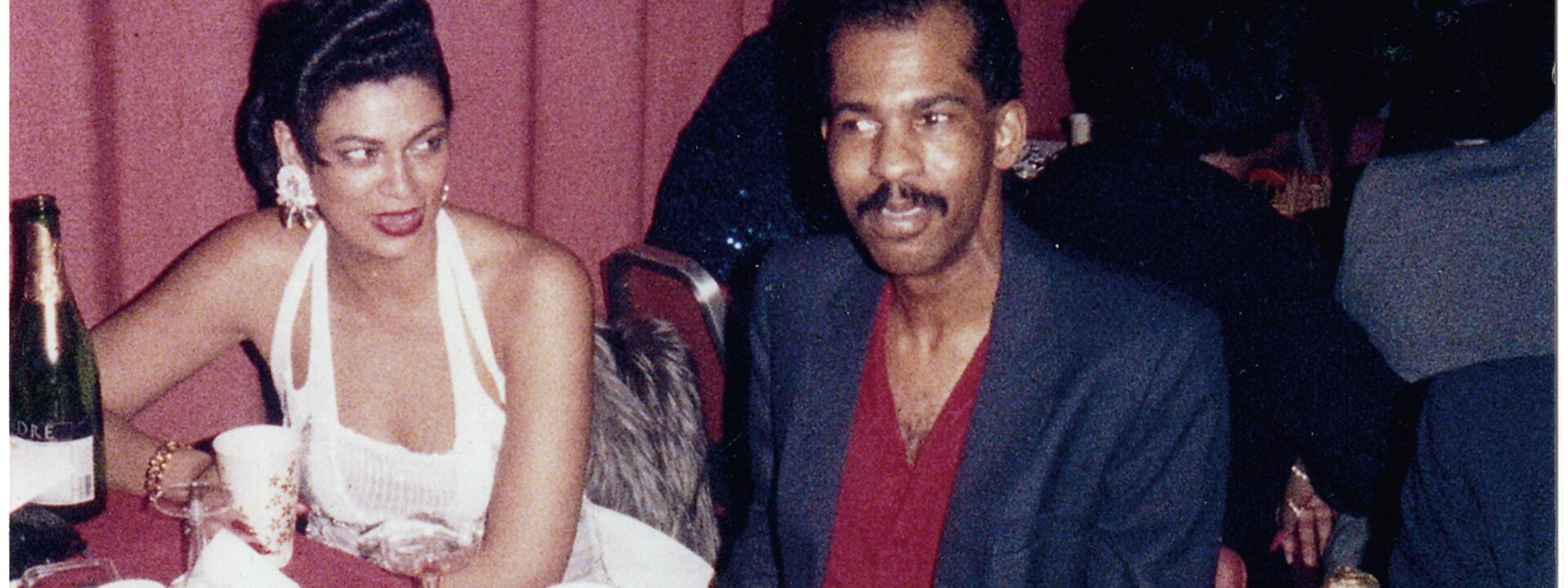

I was at an airport when I got the call—Johnny needed to move to hospice. It was almost his time, they said. I visited often, sometimes staying overnight. He loved when I helped him into a wheelchair so we could go outside. We both adored the sun, and it eased the deep chill in his bones. In those moments, it felt like we were kids again, sitting high up in the pecan tree from our childhood. I have a photo of us outside near the end—those little escapes meant everything.

Johnny passed on July 29, 1998. He was 48. We held his memorial the next Saturday at Wynn Funeral Home in Galveston. Beyoncé and Kelly sang with the other Destiny’s Child girls. They had just been touring with Boyz II Men, and now they were here, grieving. I don’t know how they made it through Amazing Grace, but they did.

Years later, in the summer of 2022, I was at Beyoncé’s home in the Hamptons for her Renaissance album release party. Blue and Rumi, then 10 and 5, had decorated the place. The album was her tribute to the house music Johnny had introduced my daughters to. I hadn’t heard HEATED yet, and as we danced, Jay suddenly said, “Listen to this.”

Then came the line—Beyoncé singing, “Uncle Johnny made my dress.” I cried and smiled at the same time. This was what Johnny wanted—to be loved, remembered. We raised a toast. “Here’s to Johnny.”

On the Renaissance tour, fans worldwide would turn to me during that line, and every time, my hand went to my heart. I wished Johnny could be there dancing with me. But I’d always spot someone in the crowd who reminded me of him, and I’d do anything to get to them—driving security crazy: “Bring him! Yes, that one!” I’d point the cameras their way. “Make sure you get them—they’re fabulous!” I collected photos of so many “Johnnys.”

Beyoncé closed the show with a massive photo of me and Johnny across the stage—me looking at him with adoring but skeptical eyes, waiting for whatever wild thing he’d say next. She’d asked me last-minute for a picture of us for the album art, and when I opened a box, that photo was right on top—Johnny making sure we picked the perfect one.

When our photo lit up stadiums worldwide, the crowd—all the young people who felt a connection to our Johnny—erupted in cheers.

“Yessss, Lucy,” I heard, Johnny’s voice so close in my ear, loud over the house music he and my daughters loved. “They know what time it is!”

Adapted from Matriarch by Tina Knowles, to be published April 22, 2025, by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Matriarch: A Memoir

$35 | $23 (Amazon)