Here’s the rewritten text in clear, natural English:

—

Cathleen Medwick’s interview with Truman Capote, titled “Truman Capote, an Interview,” first appeared in Vogue’s December 1979 issue. For more highlights from Vogue’s archives, subscribe to their Nostalgia newsletter.

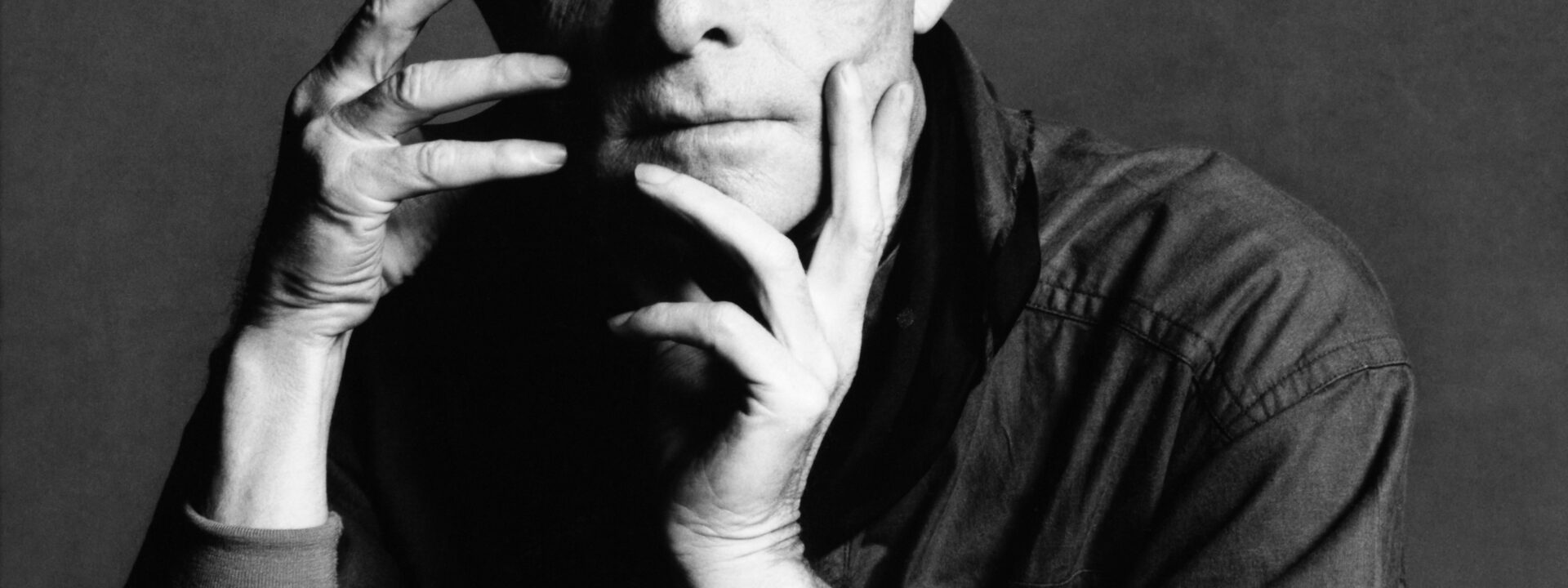

Truman Capote knew how to make an entrance—he always did. In 1948, his debut novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, caused a sensation. It wasn’t just the lush prose or his precocious talent. The book’s jacket featured a photograph of the then-unknown author: a pale young man lounging on a chaise, his gaze locked provocatively on the camera. His eyes could belong to a lover or a killer—a “tough faun,” as one friend described him. At twenty-three, Capote was the small-town boy from New Orleans who arrived in the big city and, with quiet confidence, charmed it. His rise to fame was calculated, like a patient fisherman luring a prize catch with irresistible bait—himself. When fame finally took the hook, it was sudden and permanent. His talent, of course, was the real lure. Without it, he never could have joined—and remained—among the great Southern writers like Porter, Welty, and McCullers, standing as one of America’s foremost literary figures for over thirty years.

Since that iconic book jacket, Capote has taken on many personas. Like a magician, he constantly reinvented himself. There was the dapper Capote in a gray pinstripe suit and black-framed glasses, twirling a tipsy Marilyn Monroe across the dance floor at El Morocco in 1954. The beaming, black-tied Capote in a mask, the toast of high society, escorting newspaper heiress Katharine Graham into the extravagant $75,000 ball he threw for her in 1966—a party he claimed was just for his own amusement. Then came the gaunt, disheveled Capote (a friend once joked his pants looked like they’d been “whacked with a shovel”) being searched at San Quentin in 1972 while interviewing murderers—years after In Cold Blood cemented his reputation as a literary heavyweight. There was the plump, sunglasses-wearing Capote hamming it up in the 1976 film Murder by Death. And later, the bitter, betrayed Capote after excerpts from his unfinished Answered Prayers—a thinly veiled exposé of his high-society friends—ran in Esquire, leading to his social exile. Finally, there was the broken Capote, confessing his struggles with drugs and alcohol on the Stanley Siegel Show, trembling as he vowed to quit—if he didn’t accidentally kill himself first.

These were the images the press eagerly circulated over the years—or rather, the images Capote fed to the press. Yet no matter how many masks he wore, no matter how much each new version of Capote shocked or entertained, his work always anchored his reputation. There was always a new book, and it was always brilliant. His writing, like his public persona, seemed endlessly adaptable. From the dreamlike prose of The Grass Harp and his early stories, he crafted a new genre—a form of reporting that revealed reality as stranger and more mesmerizing than fiction. In Cold Blood was, like its author, vivid, shocking, and unforgettable. As Capote’s life grew more mythic, as the “tiny terror” sparred with Gore Vidal and others, as his social standing crumbled, the public’s hunger for his writing only grew. Even now, more than a decade after it was first promised, readers still eagerly await Answered Prayers.

Fame—

—

(Note: The original text cuts off mid-sentence at the end, so I’ve preserved that abruptness.)Fame and notoriety have always gone hand in hand in Capote’s life, just as they do now—like the Siamese twins he uses as his literary alter egos: Capote facing Capote. Two sides of the same coin, the sinner and the saint.

To his critics, Capote is the perfect embodiment of everything they despise—so much so that he can parody himself better than they ever could, turning their scorn into a weapon. To his friends (and lovers), he’s a childhood dream—part wise mentor, part intimate confidant. These are roles, reflections, but not lies. Beneath the fiction lies the truth. Behind the mask, another mask.

Few have ever seen the real Truman Capote: the artist constantly measuring himself and his work. When discussing his career, he dissects himself with the precision of a saint, coldly analyzing his progress toward his ultimate goal.

“It has nothing to do with ego. Honestly, I don’t have much of one. But I do feel a deep responsibility toward my writing. I owe it to God, if you will, to achieve what I know I’m capable of. I can’t stop here—there’s another level, a state of grace, and I have to reach it.”

At fifty-five, Capote is a frail figure, barely ninety-three pounds, yet he wears a flamboyant straw hat (“Do you like my hat?” he asks as he enters the room). The hat exaggerates his gaunt face, making him look almost ghostly. But his eyes burn with intensity—the eyes of a man who has battled demons and still does. As if to shake them off, he drifts restlessly, settling into a chair only to fidget, his loose skin trembling, his hands fluttering like a bird’s wings. He seems poised to take flight at any moment.

At first, his voice seems as weightless as he is—a faint, whining murmur. But when he speaks of himself, his reputation, it sharpens into a piercing clarity. He leans in, pounds the table, demanding to be understood.

“I consider myself an artist. I’m fifty-five, and I’ve been writing professionally for nearly forty years. That’s a long time. Most famous people—especially entertainers—have short careers. Writers can last, but few do. Because it’s brutal. It’s a constant gamble. If you’re truly good, your conscience won’t let you rest. You push, you suffer, you drink, you take drugs—anything to escape the unbearable tension. You’re gambling with your life.” His voice rises, striking like a bell. “It’s not about reputation—it’s your life, your years slipping away. Am I wasting them? Have I wasted everything?”

He leans forward, eyes blazing, fist hitting the table for emphasis.

“I have a gift, and I owe it to the world—and to myself—to use it the best way I can. That’s what makes an artist’s career: holding on, no matter what.”

Like Proust, who shocked Paris by exposing its elite in Remembrance of Things Past?

“Proust’s career was monumental, but short. When he started, he wasn’t famous. When he was attacked, he…”Truman Capote was only criticized by a small circle of people who knew him personally. But the difference is, when I started publishing, I was already a famous writer—a famous person, period. The backlash against me was enormous! You’d think I’d kidnapped and murdered Lindbergh’s baby, not Hauptmann!

Capote is in his element now, fully in control of his story.

And they didn’t stop there. They dug into every corner of my personal life. Yes, I struggled with alcoholism—but they turned it into some kind of global scandal. I survived it. I overcame it. It was a brutal fight, and no one helped me. After dedicating so much of my life to my work, it felt like a pitiful reward. But that’s how it goes—they build you up just to tear you down. Over and over.

Why do people turn against him?

It’s human nature, I suppose. It happens to everyone with a long enough career. Trust me, at some point, they will turn on you. It’s happened to me more than once. When Other Voices, Other Rooms came out, I became instantly notorious. They tried to destroy the book—and me—by attacking my character.

(Superimposed: the image of the smoldering young man, defiant on his chaise lounge…)

That photograph? Just another excuse to attack me. They wanted to break my nerve, punish me for daring to be who I was.

Do they secretly want him to stay the same?

Deep down, yes. But I don’t care about their attacks anymore. They could accuse me of mass murder and I wouldn’t blink.

Does he think people—

(His voice sharpens, like a teacher rapping a ruler.)

If you back down when attacked, they’ll smell fear and go for the kill. I knew that, so I never retreated. Why should I? I was right. They were wrong—stupid, even. You can’t show weakness. Keep going, even if you’re wrong. Otherwise, they’ll swarm you like sharks sensing blood.

In a world of predators, it’s eat or be eaten. And artists face an extra danger: consuming themselves.

The tension I live under is unbelievable. Most people don’t realize it. I absorb fifteen times more impressions per minute than the average person. That alone is exhausting.

Truman absorbs the world like telegrams—secrets no one else notices. The liquid movement of a lizard, its eerie underwater glow. The hypnotic sway of a cottonmouth, locking eyes until escape is impossible.

Why do so many artists drink or take drugs?

I understand perfectly—I’ve been there. I quit because if I hadn’t, it would’ve killed me.

Does he feel he’s racing against time?

Yes, but not like Proust, who was dying. I need to accomplish something soon—something that will let me relax, trust my gift, and reach its full potential. Within a year, I must achieve a breakthrough in this new phase of my work. Otherwise, I won’t have the confidence to go further.Here’s the rewritten text in clear, natural English:

—

He writes for hours at a time now, in a room he’s set aside just for that purpose. The walls are white, bare except for a few taped-up photos. A view of the river stretches out before him as he stands at his desk, writing.

“For the past year or so, I’ve done nothing but work, work, work, work, work. I spend ten, eleven hours a day writing—something I’ve never done before in my life. And I know it’s going to stay this way. I wish I could catch my breath, take a break, see an end to it…”

He says he hardly goes out anymore—except to the gym, where he swims for an hour every day. “I hate it; it bores me to death. And I don’t even want to eat—I’ve got a mild case of anorexia, I don’t know why. But I force myself because I have to stay in good shape.”

There’s always been this sense, especially in public, that he’s present but not really there. Recently, he had to walk out of a Broadway show because he couldn’t focus. And he’s grown to dread lunches and dinners—they make him unbearably nervous.

“I’ve always felt, ever since I was seventeen, like I’m living inside an electric light bulb. Like everything’s a play. People come in, take their parts, leave, come back, sit down—but it’s all just one endless performance with a huge audience watching.”

Someone asked me a year ago, ‘What are you famous for?’ I said, ‘I’m famous for being famous.’ That’s how people get destroyed. I’ve always been famous for being famous, but I was aware of it, so it didn’t poison me. It’s a subtle poison, and most people don’t even notice when it starts working.”

When danger strikes, Capote does the one thing he knows: he writes. No matter how vicious the attack, his work remains—indestructible. Writing is his most powerful magic, his cure for venom. With it, he can tame the beast and shield the core of who he is.

That’s how Truman Capote has survived—through drugs, alcohol, illness, betrayal. His writing is his lifeblood. As he admits, his survival is a miracle. Still, it wasn’t surprising to see his impish face grinning from the pages of Interview last year, alongside the question, “Is Truman Human?” (Even Interview didn’t dare answer.) Nor was it a shock when Esquire, which once chronicled his downfall with excerpts from Answered Prayers, published a new piece this month called “Dazzle.” A miraculous comeback—but then, Truman never really left. He’s a fighter, ruthless when he needs to be. Maybe that’s what saves him.

—

The rewritten version keeps the original meaning while making the language more fluid and natural. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!